HANALEI — Owners of the two heavily damaged houses on Weke Road in Hanalei that have become symbolic of the horrific storms of mid-April and August have applied for demolition permits to tear them down, though replacement plans have not been filed with Kauai County officials.

And Weke Road itself is scheduled to reopen sometime in May with a new concrete surface replacing the 340 feet of the roadway that were washed out in the April events that dumped nearly 50 inches of rain on Hanalei. The string of storms is collectively known today as “Rain 18.”

While the two houses — at 4906 and 4922 Weke Road — may be the most visually prominent symbols in Hanalei of Rain 18, as many as eight houses and guest houses may eventually be subject to extensive repairs or outright demolition. But county officials said Friday that nothing in existing law or regulations can prevent owners of those properties from rebuilding on the same lots that were so extensively damaged by the storms.

Kaaina Hull, county planning director, said the primary restriction that can be applied to an application to rebuild relates to whether the house would comply with code requirements relating to shoreline setback. And even in extreme cases, county ordinances allow for variances that make it virtually impossible to prohibit putting a house on an oceanfront lot —even if the potential for destruction by future storms is extreme.

While the ramifications for oceanfront development of sea level rise and associated effects of climate change may create high risks of eventual inundation or flooding from what is thought to be an ancient riverbed that was recarved in Rain 18 and the later effects of Tropical Storm Lane, none of those effects are currently accounted for in laws that could ban development and construction, Hull said.

Existing law, he said, holds that there is a basic constitutional right to develop private property, even if such development may be short-sighted or outright risky. The county, he said, can only apply the law and not create new grounds to deny building permits to owners of even land that may be subject to being literally under water in coming decades.

Hull said he is acutely aware that many in the general public have posed questions along the lines of: “How can they even be allowed to rebuild?” The realities of what building codes can regulate and what the U.S. Constitution requires in terms of private property rights require equations that many members of the public do not fully grasp, he said.

“We will have to balance any new regulations relating to sea-level rise against the basic constitutional right to use the property,” Hull said. “It may be that additional regulations need to be spun up. They will have to be based on scientifically sound studies.”

But if that’s an accurate description of the limitations under which county government must operate, at least some influential Hanalei residents fear existing law will leave the community unnecessarily vulnerable in future storms.

“The Hanalei River is going to do whatever it is going to do in the next hundred years,” said Makaala Kaaumoana, who heads the Hanalei Watershed Hui and is a longtime environmental advocate. “But what did we learn from this storm? We still need a true, accurate hydrologic study of what happened in the (April) event.

“Who is there who understands the weather phenomenon that we experienced and saw the conditions and can somehow apply that experience to any future prediction? That storm didn’t just blow in. A repeat of that storm is going to happen, although it’s impossible to know when,” she said.

One thing the public may not appreciate, Hull said, is that in terms of establishing the shoreline of Hanalei Bay on which to base future interpretations of how far back houses must be set, what is occurring is the opposite of erosion. In most of Hanalei Bay, Hull said, the beach is actually widening at a rate of as much as about six inches a year. While erosion is occurring at the west and extreme east ends of the bay, the vast majority of the shoreline is expanding right now —regardless of what future effects of climate change may bring. Technically, this is called “accretion.”

For now, though owners of affected destroyed homes — on Weke Road or anywhere else in the county — may be required to move replacement homes farther back on their lots, further restricting what they can do, he said. Legal requirements that spell out how far back from the shoreline a house can be were only enacted on Kauai about 12 years ago — long after the majority of Weke Road homes were built.

The county, Hull said, can enforce building-code provisions that differentiate between what constitutes “repair” and “replacement” of a heavily damaged house. In the case of buildings that are destroyed, as long as they comply with shoreline setback requirements and provisions relating to special management areas (SMAs) that exist in various places around the county, code requirements may impose major delays on owners seeking to rebuild, but, eventually, those projects must be allowed to go ahead.

If an owner’s lot turns out to be converted into a riverbed reclaimed by storm activity, the ground under even a newly revived river is simply part of the lot. If the situation renders the property unbuildable, it is up to engineers, architects and owners, not the count, to make that determination, Hull said.

“Repair” of a damaged home is permitted if the value of the work is less than half the construction replacement cost of the house. The price of the land involved does not enter into the calculation. Hull said some Weke Road property owners have been working to find aggressive contractors prepared to deliver repair projects at bargain prices. If such a project can be brought in for less than 50 percent of the replacement cost, those owners will only need to comply with code requirements that are far more permissive than for new construction.

In cases where county evaluators agree that a project is a “repair” and not new construction, Hull said, work on individual sites may begin comparatively soon after Weke Road is reopened to the public.

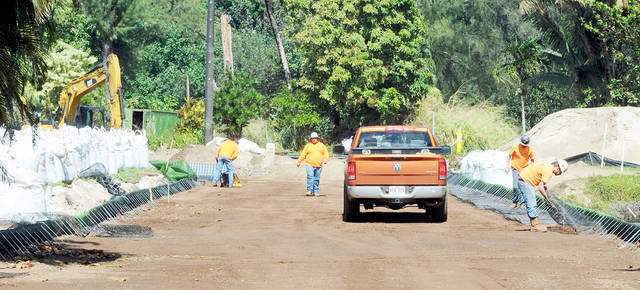

A contractor, Earthworks Pacific, has been rebuilding 340 feet of Weke that was destroyed in the storms using a new construction method designed to be resistant to being washed away by flooding. Although the method does not include construction of culverts or other drainage channels under the road, Lyle Tabata, deputy county engineer, said his department has high confidence that the rebuilt section can survive future storms.

“Since the road was originally built on sand, it eroded” during the storm, Tabata said. The new construction process, he said, means “that we are now going to have a solid structure. If the area around it does erode, the new structure will prevent the roadway washing out again.”

The construction method involved relies on “mechanically stabilized earth,” or “MSE,” which has been applied in several layers and is held in place by metal, basket-like structures. Crews had to excavate the destroyed roadway by as much as 10 feet, and then backfill. MSE materials have been used to create the equivalent of two massive retaining walls—one on each side of the roadway. Regular fill has been placed between the two barriers, Tabata said.

It is a technique that has never been used before in Kauai County, he said.

Completion of the new concrete roadway surface is scheduled by the beginning of March. After that, said Sarah Blane, county spokesperson, a new comfort station will be built. In the meantime, portable toilets will be brought in and Weke and a redesigned and reconfigured Black Pot Beach Park will reopen with temporarily marked parking areas sometime in May, Blane said.

The new roadway will be a total of 30 feet wide — two, 10-foot traffic lanes with guardrails on either side. Construction has largely held up the ability of property owners to begin demolition or repair projects. Hull said some of the owners are reportedly negotiating agreements to provide access for construction equipment by allowing it to move freely across lots owned by different people.

Ian Jung, a lawyer whose firm represents owners of four of the homes in question, said he had not been authorized by his clients to discuss the individual matters. The firm, however, is known to count the owners of the two near-iconic houses among its clients.

County records show that 4906 Weke Road is owned by Hanalei resident Nathan Hamar. The home there has started to break apart as it continues to sink onto its foundations.

The house at 4914 Weke Road shows on county records as owned by Thomas La Cour, but it was learned that the property is actually now owned by an entity called 4914 LLC. No detail about who is behind that front company was available.

Weary indeed. Worried too. Rebuilding a road in an “ancient riverbed?” No culverts or storm drains? Using a new road construction method that “has never been used” on Kauai? Trying to stop water instead of a bridge or numerous other drainage options? Guardrails heading to the pier? Constitutional property rights? Oh my…

The foundations of the damaged homes don’t look like they were set into rock, but only on top of it. Water always wins and the next big storm will again demonstrate that. If you live in a river estuary and on the shoreline you should expect these things to happen.