NEW YORK — In early November, word began to leak that Amazon was serious about choosing New York to build a giant new campus. The city was eager to lure the company and its thousands of high-paying tech jobs, offering billions in tax incentives and lighting the Empire State Building in Amazon orange.

Even Governor Andrew Cuomo got in on the action: “I’ll change my name to Amazon Cuomo if that’s what it takes,” he joked at the time.

Then Amazon made it official: It chose the Long Island City neighborhood of Queens to build a $2.5 billion campus that could house 25,000 workers, in addition to new offices planned for northern Virginia. Cuomo and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio, Democrats who have been political adversaries for years, trumpeted the decision as a major coup after edging out more than 230 other proposals.

But what they didn’t expect was the protests, the hostile public hearings and the disparaging tweets that would come in the next three months, eventually leading to Amazon’s dramatic Valentine’s Day breakup with New York.

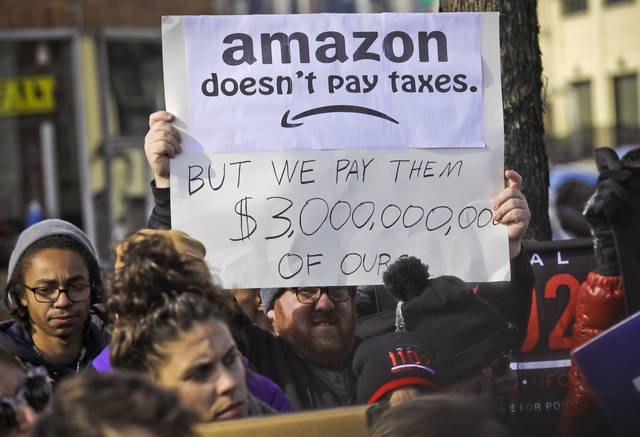

Immediately after Amazon’s Nov. 12 announcement, criticism started to pour in. The deal included $1.5 billion in special tax breaks and grants for the company, but a closer look at the total package revealed it to be worth at least $2.8 billion. Some of the same politicians who had signed a letter to woo Amazon were now balking at the tax incentives.

“Offering massive corporate welfare from scarce public resources to one of the wealthiest corporations in the world at a time of great need in our state is just wrong,” said New York State Sen. Michael Gianaris and New York City Councilman Jimmy Van Bramer, Democrats who represent the Long Island City area, in a joint statement.

The next day, CEO Jeff Bezos was on the cover of The New York Post in a cartoon-like illustration, hanging out of a helicopter, holding money bags in each hand, with cash billowing above the skyline. “QUEENS RANSOM,” the headline screamed. The New York Times editorial board, meanwhile, called the deal a “bad bargain” for the city: “We won’t know for 10 years whether the promised 25,000 jobs will materialize,” it said.

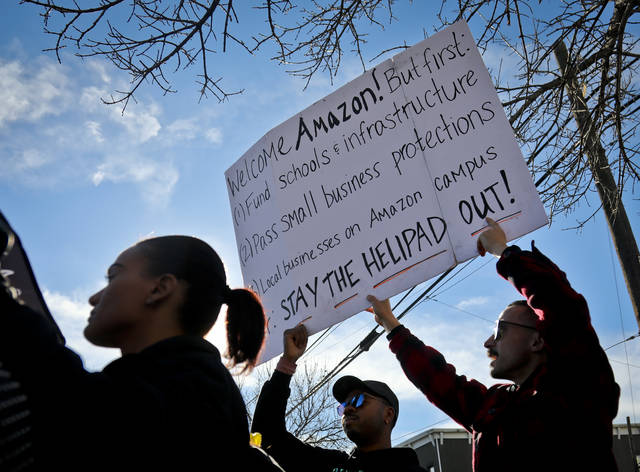

Anti-Amazon rallies were planned for the next week. Protesters stormed a New York Amazon bookstore on the day after Thanksgiving and then went to a rally on the steps of a courthouse near the site of the new headquarters in the pouring rain. Some held cardboard boxes with Amazon’s smile logo turned upside down.

They had a long list of grievances: the deal was done secretively; Amazon, one of the world’s most valuable companies, didn’t need nearly $3 billion in tax incentives; rising rents could push people out of the neighborhood; and the company was opposed to unionization.

The helipad kept coming up, too: Amazon, in its deal with the city, was promised it could build a spot to land a helicopter on or near the new offices.

At the first public hearing in December, which turned into a hostile, three-hour interrogation of two Amazon executives by city lawmakers, the helipad was mentioned more than a dozen times. The image of high-paid executives buzzing by a nearby low-income housing project became a symbol of corporate greed.

Queens residents soon found postcards from Amazon in their mailboxes, trumpeting the benefits of the project. Gianaris sent his own version, calling the company “Scamazon” and urging people to call Bezos and tell him to stay in Seattle.

At a second city council hearing in January, Amazon’s vice president for public policy, Brian Huseman, subtly suggested that perhaps the company’s decision to come to New York could be reversed.

“We want to invest in a community that wants us,” he said.

Then came a sign that Amazon’s opponents might actually succeed in derailing the deal: In early February, Gianaris was tapped for a seat on a little-known state panel that often has to approve state funding for big economic development projects. That meant if Amazon’s deal went before the board, Gianaris could kill it.

“I’m not looking to negotiate a better deal,” Gianaris said at the time. “I am against the deal that has been proposed.”

Cuomo had the power to block Gianaris’ appointment, but he didn’t indicate whether he would take that step.

Meanwhile, Amazon’s own doubts about the project started to show. On Feb. 8, The Washington Post reported that the company was having second thoughts about the Queens location.

On Wednesday, Cuomo brokered a meeting with four top Amazon executives and the leaders of three unions critical of the deal. The union leaders walked away with the impression that the parties had an agreed upon framework for further negotiations, said Stuart Appelbaum, president of the Retail Wholesale and Department Store Union.

“We had a good conversation. We talked about next steps. We shook hands,” Appelbaum said.

An Amazon representative did not respond to a request for comment for this story.

The final blow landed Thursday, when Amazon announced on a blog post that it was backing out, surprising the mayor, who had spoken to an Amazon executive Monday night and received “no indication” that the company would bail.

Amazon still expected the deal to be approved, according to a source familiar with Amazon’s thinking, but that the constant criticism from politicians didn’t make sense for the company to grow there.

“I was flabbergasted,” De Blasio said. “Why on earth after all of the effort we all put in would you simply walk away?”

———

Associated Press Writers Alexandra Olson and Karen Matthews in New York, and David Klepper in Albany, New York, contributed to this report.