NEW YORK — Fitting for a man who saw so much darkness in the world, Lyndon LaRouche died on the fringes this week, his name little known to anyone under 50, his death rumored online a day before mainstream outlets confirmed it.

His influence, however, will surely outlast him.

“LaRouche is the granddaddy of the conspiracist culture that is poisoning our culture today,” says Matthew Sweet, who wrote about LaRouche last year in “Operation Chaos: The Vietnam Deserters Who Fought the CIA, the Brainwashers, and Themselves.”

“Some of his ideas were insanely exotic — the idea that the Queen was plotting World War III, for example,” Sweet says. “But his fantasies about George Soros proved rather more contagious. Alex Jones, Roger Stone, those figures in the US who made it their business to produce seductive, confusing, paranoid noise, see him as an elder statesman. They’re toiling in the same dismal field.”

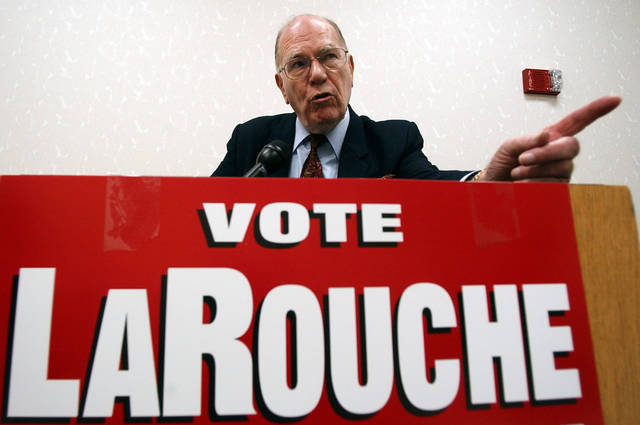

LaRouche, who died Tuesday at age 96, was an eight-time presidential candidate who never received more than a tiny percentage of the vote. But he had a global following, and he has been praised by some people now very much in the news.

Stone, the longtime associate of President Donald Trump who has alleged the “Deep State” is trying to kill him, has said he was “very familiar with the extraordinary and prophetic thinking” of LaRouche. He added that LaRouche’s ideas had an “important backstage role” in electing the very untraditional Trump.

“A friend of mine, a good friend of mine, and a good man,” Stone called him in 2017.

Jones, being sued for his allegations that the Sandy Hook shootings were a hoax, has interviewed LaRouche on his Infowars program and shared conspiracies about everything from the “Rothchilds” (a code word for Jews) of international banking to the evils of British power.

LaRouche’s thinking was shaped by the post-World War II culture. He has called himself a Franklin D. Roosevelt Democrat who became convinced that Harry Truman and other future presidents were pawns of the British, whose power dated back to the Roman Empire.

He indulged in many of the conspiracy theories common to his time, such as believing that President John F. Kennedy was assassinated by government forces because he was a threat to the establishment. He has called global warming a hoax (as has Trump), dismissed the Holocaust as “mythical” and disputed medical warnings about AIDS as lies.

But LaRouche also was unique for the extremity of his rhetoric and for his blurring of the far left and far right.

Jesse Walker, author of “The United States of Paranoia: A Conspiracy Theory,” published in 2014, says LaRouche’s rise coincided with a new kind of conspiracy thinking.

“Before, people tended to adopt the conspiracy theories associated with their own circumstances — there were liberal conspiracy theories, conservative conspiracy theories, and so on,” he says. “Now there was a growing interest in conspiracies — in themselves, so that, for example, you might start out interested in left-wing theories about the CIA but then check out what this fellow on the right has to say about banks.”

Gradually, Walker says, “this left/right crossover became a full-fledged subculture. LaRouche wasn’t himself a part of that subculture, but his mix of far-left and far-right ideas mirrored it in some ways — and helped guarantee that the members of the subculture would pay attention to him, though they never did agree on how seriously to take him.”

Today, suspicion of conspiracy has never been more widespread or more amplified. But American conspiracies long predate LaRouche and his era.

New Englanders in the 17th century accused women of being witches, tried them, and, in some cases, hanged them. In the 18th century, colonists speculated that a British statesman — John Stuart, 3rd Earl of Bute, was a behind a cabal to tyrannize Americans. A century later, Lincoln assassination conspiracists blamed everyone from the pope to the Confederacy’s Jewish secretary of state, Judah P. Benjamin.

“It’s much safer to believe that ‘someone secretly did it with a giant diabolical plan’ rather than that a single person can change our entire world at any moment,” says Brad Meltzer, the best-selling novelist whose nonfiction books include “The First Conspiracy: The Secret Plot to Kill George Washington.”

“We don’t like being scared. It’s much safer to blame others — especially when it’s a group of a different race, religion or nationality,” Meltzer says. “As long as there are believers, there will be those who take advantage of them, riding them to power. People want to believe. Show me your favorite conspiracy theory and I’ll show you who you are.”