LONDON — Don McCullin’s most famous photographs burn with the physical and emotional brutality of conflict: a shell-shocked American soldier in Vietnam, a starving woman and child in Nigeria’s breakaway Biafra.

But don’t call him a war photographer.

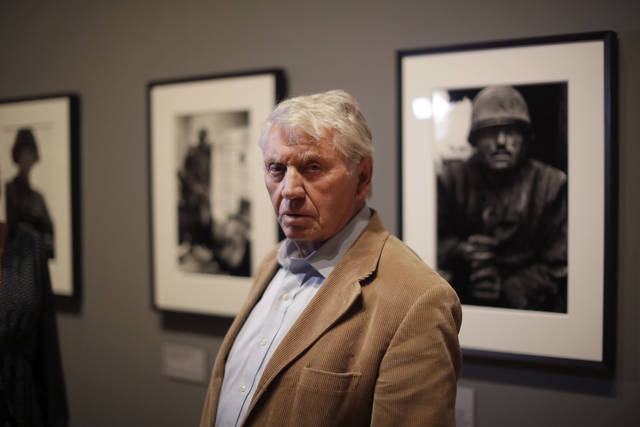

“I hate that,” the 83-year-old British photojournalist said Monday, sitting in an exhibition of six decades’ worth of his images of damaged people, ravaged landscapes and scarred cities. “I’ve willfully changed direction because I didn’t want to get stuck in the war direction, people calling me a war photographer.”

The retrospective of more than 250 photographs opens Tuesday and runs to May 6 at Tate Britain , the country’s foremost gallery of U.K. art. But don’t call McCullin an artist.

“I hate that, too,” said McCullin, who is charming with a combative undercurrent. “I’m not an artist. I’m a photographer, and that’s all there is to it.”

McCullin’s career began almost by chance, with a photo of young gang members he knew from Finsbury Park, the tough London neighborhood where he grew up. A shot of the group — “The Guv’nors” — standing in a bombed-out building, had a powerful combination of squalor and swagger that caught the attention of British newspapers.

“Once that was published in The Observer, I could see a life for myself rather than hanging around with those boys,” McCullin said. “So I made this journey into photography, and it’s been extraordinary, really.”

McCullin plunged into many of the 20th century’s conflict zones: Cold War Berlin, Biafra, Vietnam, Cambodia, Congo, Lebanon, Northern Ireland, Iraq.

His images, always in black and white, powerfully capture the emotions of war — the raw grief of a woman in Cyprus who has just learned of her husband’s death; the devastation of an American GI; the exhilaration of youths in Northern Ireland throwing stones at soldiers.

His lens looked just as unflinchingly at his home country. From the 1950s onwards, McCullin captured a side of Britain scarred by poverty, violence and decay. It’s tough stuff, though his images of holidaymakers at the seaside have a defiant cheerfulness, and there is great dignity in his close-up portraits of careworn and homeless inhabitants of Britain’s cities.

McCullin survived physical danger and brushes with death. A glass case at the exhibition holds a Nikon camera that stopped a bullet hitting him in Cambodia.

He didn’t escape an emotional toll, and in recent years has turned to quieter subjects — “to eradicate the past,” McCullin says in an exhibition note. Recent works include photos of the strange, watery landscape of the Somerset Levels near his home in southwest England.

McCullin acknowledges that even these rural landscapes end up “looking like the First World War,” shot on black and white film — never digitally — and printed by McCullin with his signature in glowering intensity.

He hasn’t abandoned war zones altogether. There are images of devastated Homs in Syria taken on a trip last year.

McCullin has sometimes wondered if his work was worth it, since wars continue unabated. But he is amazed by how far it has taken him.

“It’s taken me all around the world many times,” he said. “And I’ve got a great love of culture now. I started out with nothing. There was never a book in my house; there was only violence in my house when I was a boy.”

He says he doesn’t suffer from post-traumatic stress: “I’ve cured myself by doing these landscapes.”

“I grew up with quite a strong backbone, and I’ve kept it going,” McCullin said. “Now I’m getting old and lame and I’m having heart attacks and all that kind of stuff. I just think that’s part of the stuff I have to beat.

“That sounds a bit macho,” he added, a touch apologetically. “But it’s not meant to be macho — it’s meant to be a ‘You can do it’ kind of thing.”

———

Follow Jill Lawless on Twitter at http://Twitter.com/JillLawless