A yellowish-green, masked bird flits through the ohia trees of Kauai’s Alakai Swamp, tagging lehua blossoms and searching for bugs.

It’s difficult to spot, and not just because of its small size.

There are fewer than 1,000 akekee birds, a type of Hawaiian honeycreeper endemic to Kauai, left in the forest.

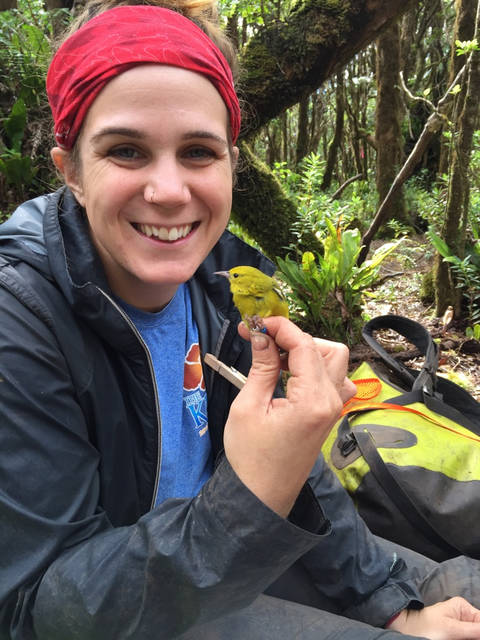

Their numbers are dwindling and researchers are ramping up efforts to keep them from disappearing — researchers like Maria Costantini, a doctorate student with the Kauai Forest Bird Recovery Project, who is studying the diet and microbiomes of akekee and the endangered akikiki to unlock ways of preserving the species.

The University of Hawaii at Manoa student just landed a grant to travel to the American Ornithological Society conference next summer in Anchorage, and hopes to spread the word about the endangered birds with others in the field.

The research and travel grant was for $5,000 with an additional $1,500 for the conference.

“The conference is the biggest ornithology-based conference in the country and personally, it’s a chance for me to get out there and present my research and start making an impact,” Costantini said.

Since 2015, Costantini has been a field assistant for KFBRP, a program of the state’s Division of Forestry and Wildlife dedicated to conservation of Kauai’s native forest birds.

Hailing from New Jersey, she started her post-secondary education as a pre-med student who decided she wouldn’t be happy with a lifelong medical career.

“I had a moment to be real with myself and I became a biology major, then I took an ornithology class and realized I wanted to get into conservation and go into grad school,” Costantini said.

She made her first trip out to the West Coast for an internship at Point Blue Conservation Science straight out of college, where she was working hands-on in the field banding birds. “Having that be my first job experience, I fell in love with it,” she said. “I was lucky.”

After a couple attempts at applying for seasonal employment with KFBRP, she landed a job on Kauai.

The more time she spent with researchers and field workers at KFBRP, the more Costantini thought about completing a PhD.

“I had my masters at that point and didn’t think I’d ever go back for my PhD. If I did, I knew it had to be something I was passionate about,” she said.

“I thought, ‘This is something I could see myself spending six years dedicated to.’”

Now she’s in her third year of school and is researching food sources of the akekee and akikiki — two species that are believed to only eat arthropods, but whose diets have not been well researched.

Costantini is collecting fecal samples from these two bird species and matching the DNA sequences within to arthropod DNA to figure out what specifically is important to their diet.

“Are they specified in what they eat, maybe things that only occur in certain parts of the Alakai, or are they more generalized?” she said. “Maybe if we can find what’s important in their diets we can link that to other habitats.”

Mosquitoes and their vectored avian malaria and other diseases have been creeping up in elevation, thanks to warming temperatures and shrinking endangered forest bird habitat.

Eliminating mosquitoes from their habitat is still being researched and is seen as imperative to their survival. If that is accomplished, Costantini’s research could inform best places to reintroduce the species.

Hand-in-hand with diet is the microbiome within the birds — the bacteria and other microbes in the gut that are connected to overall health and fitness.

Much microbiome research has been done on humans, but with the research spreading to non-human animals as well, Costantini thinks it might play a big role in keeping the species alive in captivity as well as in the wild.

“A healthy microbiome can be easily disrupted potentially by changing habitat or if the prey base is changed, and that is tied to how the animal works in general,” she said.

The two species have been in captivity for three years as a way of preservation, and studies have shown that captivity changes the microbiome of other animals.

It doesn’t always mean that a change in the microbiome will affect the health of the animal negatively, but Costantini wants to see how the microbiome is being impacted and to identify ways of keeping birds health through captivity and through release back into the wild.

“As their habitat degrades, that could be affecting their microbiome and ability to fight off things like avian malaria,” she said. “It’s all kind of linked and it’s important to understand.”

I’ve known for a fact that the use of natural gas canisters that generate CO2 gas and has a trap for female mosquitoes worked on my friend’s home in Waihiawa a forested area known for large amounts of mosquitoes.

He had two of these canisters working an area around 1 1/2 acres and I never got bitten when outside for over an hour. These contraptions really work and should also work in forested area where these endangered birds reside in.

The only problem is that people would steal these prophane canisters, but if the State put cameras that will help. Its a solution that can be implimented right away.