The common image of the late journalist Hunter S. Thompson is one of a drug-induced writer who rode with the Hells Angels, often shot up his red IBM Selectric typewriter and helped Chicano attorney Oscar Zeta Acosta burn the lawn of a California judge.

But a new book on the counterculture crusader attempts to dig deeper into the mission of a writer who pushed “gonzo journalism” — a style of journalism written without claims of objectivity and with the journalist at the center.

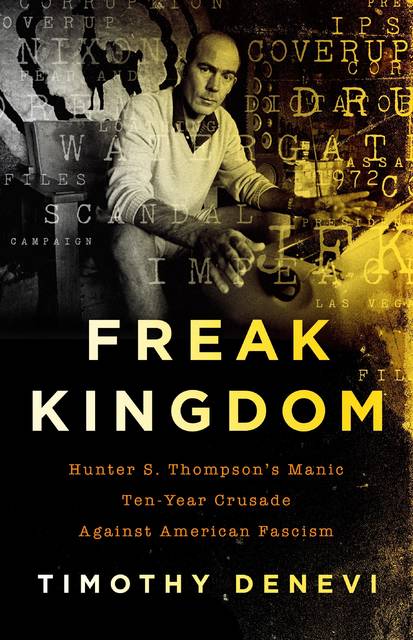

“Freak Kingdom: Hunter S. Thompson’s Manic Ten-Year Crusade Against American Fascism” by Timothy Denevi looks into the events of the turbulent 1960s and 1970s that drove Thompson to literary journalism and his desire to tackle what he saw as a rising tide of fascism in the United States. That included the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, the persistence of the Vietnam War and the rise of President Richard Nixon and his monitoring of activist groups. For Thompson, these events were an attack on the essence of the foundation of the United States and humanities. He decided early on to use his skills as a journalist to combat the rise of a totalitarianism event when it affected his mental state, his marriage and his health.

For example, Denevi writes that after the police attack on anti-war protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Thompson escaped to his Chicago hotel room to contemplate the image of police beating journalists. “His clothes stank with chemicals. His gut aches,” Denevi writes. “His entire body was shaking. He couldn’t write. None of it made sense.”

Unlike other portrayals of Thompson as a simplistic alcohol-driver journalist who brushed off identity politics, Denevi’s book argues that Thompson was indeed disturbed by the plight of young protesters, Chicanos and other minorities as the federal government sought to quiet dissent. He wouldn’t be silent, especially during the Nixon presidency.

Denevi, an assistant professor in the MFA program at George Mason University, crafts his biography like a nonfiction novel, letting his research unfold in a capitating narrative that places readers at some of the most important episodes of Thompson’s career.

The biography is the latest entry into the lives of Thompson and his counterculture pal, Acosta. The PBS documentary “The Rise and Fall of the Brown Buffalo” that aired earlier this year touched upon the pair during the Chicano Movement in Los Angeles.

The renewed interest in Thompson comes amid self-reflection by many journalists in the era of President Donald Trump and worries over fraudulent news sites.

Denevi’s work reminds us that the persistent concern about totalitarianism overwhelming free speech isn’t something new. And 50 years ago, one journalist decided to do something about it.

———

Online:

http://www.timdenevi.com/

———

Associated Press Writer Russell Contreras is a member of The Associated Press’ race and ethnicity team. Follow Contreras on Twitter at http://twitter.com/russcontreras