WICHITA, Kan. — Access to the ballot box in November will be more difficult for some people in Dodge City, where Hispanics now make up 60 percent of its population and have remade an iconic Wild West town that once was the destination of cowboys and buffalo hunters who frequented the Long Branch Saloon.

At a time when many rural towns are slowly dying, the arrival of two massive meatpacking plants boosted Dodge City’s economy and transformed its demographics as immigrants from Mexico and other countries flooded in to fill those jobs.

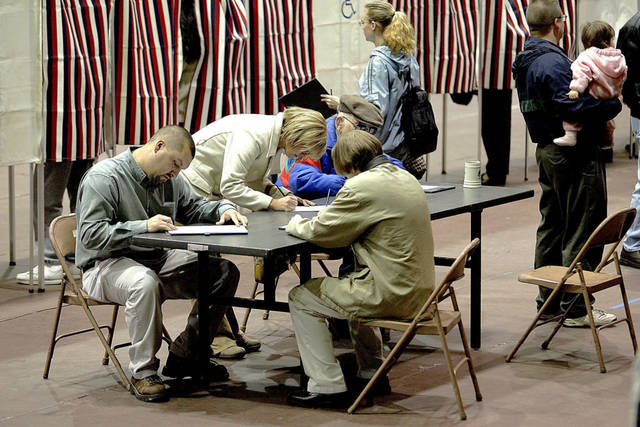

But the city located 160 miles (257 kilometers) west of Wichita has only one polling site for its 27,000 residents. Since 2002, the lone site was at the civic center just blocks from the local country club — in the wealthy, white part of town. For this November’s election, local officials have moved it outside the city limits to a facility more than a mile from the nearest bus stop, citing road construction that blocked the previous site.

“It is shocking that we only have one polling place, but that is only kind of scratching the surface of the problem,” said Johnny Dunlap, chairman of the Ford County Democratic Party. “On top of that, not only is it irrational and ridiculous that we have only one polling place, but Dodge City is one of the few minority majority cities in the state.”

A Democratic Party database compiled from state voter data shows Hispanic turnout during non-presidential elections is just 17 percent compared to 61 percent turnout for white voters in Ford County in 2014.

Dodge City’s turnout is below the national turnout rate of 27 percent among Latino eligible voters in 2014, which in itself was a record low that year for the country, according to the Pew Research Center .

“That is terrible,” Dunlap said of the sole polling site’s former location in a white neighborhood. “What that has contributed to is a way below average Hispanic turnout in voting in Dodge City,” Dunlap said.

Hispanic voters tend to vote Democratic and could be a factor in Kansas’ tight governor’s race featuring a champion of immigration restrictions, Republican Kris Kobach, against Democratic state Sen. Laura Kelly.

Some local voters and the American Civil Liberties Union have long criticized the use of a lone Dodge City polling site even before its move just weeks before the midterm election.

That single polling site services more than 13,000 voters in the Dodge City area, compared to an average of 1,200 voters per polling site at other locations, said Micah Kubic, executive director of the ACLU in Kansas.

Dodge City voters sometimes have to wait more than an hour in line to vote, and freight trains frequently block intersections at railroad tracks that split the town, Dunlap said.

Ford County Clerk Debbie Cox did not return messages seeking comment. Kansas Elections Director Bryan Caskey said Cox had no choice but to move the polling site due to the road construction, adding she did the best she could to find a suitable location. She also contacted every voter and sent out advance voting applications in English and Spanish, he said.

Dodge City had multiple voting locations until the American with Disabilities Act in 2002 imposed more stringent requirements for accessibility to polling places, Dunlap said.

Kansas is not the only state that has closed polling sites. Polling places across the country have also been shuttered since the U.S. Supreme Court in 2013 struck down parts of the Voting Rights Act. A 2016 research report from the civil rights coalition Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights found local officials had shuttered 868 polling places in the three years after the court’s ruling.

Another Kansas county also has cut the number of polling places for November, although the Dodge City situation is the only place where voting rights activists have raised concerns.

This November, some Barton County voters will have to travel 18 miles to get to their closest polling site after officials there cut the number of polling places from the 23 that were open for this year’s primary to 11 for the general election, according to Barton County Clerk Donna Zimmerman.

Zimmerman said she consolidated them to save money in hiring poll workers. The county of about 27,000 residents in central Kansas wanted to “test the waters” to see if it could get by with fewer voting machines at fewer sites, she said.

“I watched as a kid the pain of losing a school and losing the post office and losing the grocery store and now losing the voting location and so it is something that is very near and dear to my heart,” Zimmerman said of her decision. “It is a tough choice to move a voting location and it is certainly not one that didn’t happen with considerable thought.”