KATHMANDU, Nepal — Animal-rights campaigners are hoping this year’s festival season in Nepal will be a little less bloody.

During the 15-day Dasain festival that began this week in the Himalayan country, families fly kites, host feasts and visit temples, where tens of thousands of goats, buffaloes, chickens and ducks are sacrificed to please the gods and goddesses as part of a practice that dates back centuries.

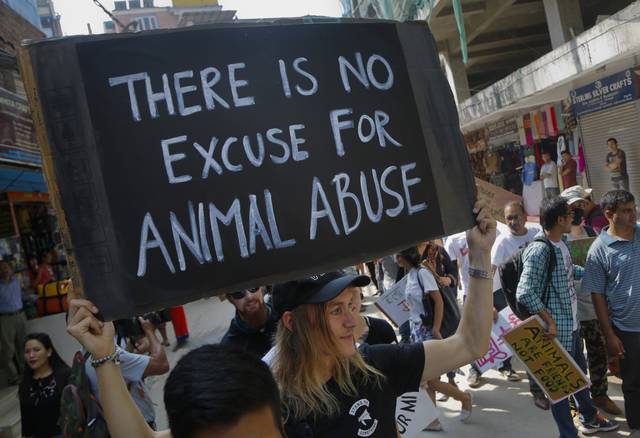

Animal rights groups are hoping to stop —or at least reduce— the slaughter, using this year’s campaign as a practice run to combat a much larger animal sacrifice set for next year at the quinquennial Gadhimai festival.

Such a campaign is novel in Nepal, where four out of five people are Hindu and animal sacrifice is a deeply rooted tradition.

Activists first organized after the Gadhimai festival in 2009, when an estimated 250,000 animals were killed at a single temple in southern Nepal.

Images of carcasses piled up on an open field were widely published and broadcast. Though there are no official data, fewer animals were believed to have been sacrificed at the subsequent Gadhimai festival in 2014, according to rights group Animal Nepal.

The number of buffalo sacrifices alone dropped from 20,000 in 2009 to 3,000 in 2014, said campaigner Pramada Shah.

“We are very few campaigners but we have a very loud voice. We are a loud minority,” Shah said.

Shah and other campaigners are visiting temples where animals are slaughtered and where devotees line up around the blood-soaked floors, offering the blood to the temples’ idols.

They are hanging banners and distributing pamphlets denouncing the practice and speaking to devotees, hoping to persuade them to take the animals they’ve purchased for sacrifice to animal sanctuaries instead.

At the Bhandrakali temple in the heart of Nepal’s capital, Kathmandu, priests and volunteers prepared for the estimated 100,000 devotees expected to visit during the festival. It is one of the main sites for animal sacrifices.

One of the priests, Anuj Pujari, said that while the number of devotees had increased, there appeared to be fewer animals brought for sacrifice.

“It is because more and more people are now against” it, he said.

Truckloads of goats were brought in from other parts of Nepal and neighboring India to Kathmandu’s goat market.

Chandra Pokhrel, who has been selling goats for the last two decades, said sales for this year’s Dasain festival were down compared to previous years.

Krishna Prasad Dhangal, a shopkeeper and devotee who was at the market to purchase animals for sacrifice, defended the practice.

“It is a tradition that our fathers and grandfathers have followed and we will continue to follow this path. We believe offering the blood to the goddess Kali will please her and bless us. The meat is not wasted and we distribute it with neighbors and we all feast,” he said.