No going home for many Hondurans deported back to brutality

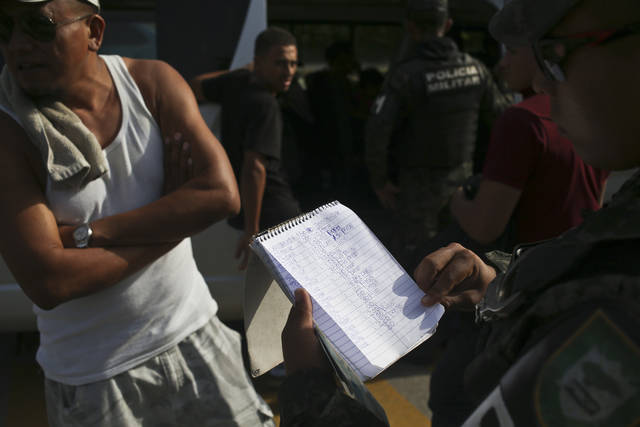

In this July 4, 2018 photo, a military police officer looks at a notebook found hidden inside a public bus, as he searches several men who were the bus in San Pedro Sula, Honduras. The notebook, which no one claimed to be the owner of, appears to list names and extortion payments, due and paid, by shop owners, drivers, etc. No one was detained during the search of bus passengers, but the notebook was confiscated by police. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

In this July 1, 2018 photo, Larissa and her husband eat a lunch of fish on his break from a construction job in the department of Yojoa, Honduras. The Mara Salvatrucha gang, also known as MS-13, came for their 14-year-old son, aiming to recruit him, but when he refused they beat him up, kicking him in the face and breaking his nose. The family failed to migrate to the U.S. when they were deported home from Mexico, but will try again. Three of Larissa’s cousins died young after being recruited by the gangs. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

In this July 1, 2018 photo, a man who prefers not to give his name for fear or gang member retaliation, wraps a shirt around his forehead to protect his head and neck as he works as a construction laborer in the department of Yojoa, Honduras, where he worked to build a home to save money for his family to migrate again to the U.S. On April 22, 2001, the man was shot by gang members 14 times when he failed to come up with extortion money but survived after being left for dead. His son and 8-year-old daughter left on a northern-bound bus, but in Mexico he and his wife came across a security roadblock, and lacking proper documents, were sent back to Honduras. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

In this July 9, 2018 photo, a woman breaks down crying on the perimeter of a crime scene where her only son Javier Antonio Santos, 18, was killed during a shootout with military police, where an officer also died, in the Chamelecon neighborhood of San Pedro Sula, Honduras. The two youths who died in the shootout are alleged by police to be Mara gang members, while the mother cried that he was not. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

In this Aug. 2, 2018 photo, family members of slain Ronald Blanco clean his blood from the alleyway of the Japon neighborhood where the Barrio 18 gang operates Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Family members sprinkled holy water and prayed at the site before working to wash away the blood stains, as passing neighbors gave them their condolences. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

In this July 27, 2018 photo, 15-year-old Jus, who did not want to give his last name for security reasons, works on composing songs at the shelter where he lives that takes in deported migrant youths who cannot return home due to high violence in their communities, where they risk getting forced into gangs, in Tegucigalpa, Honduras. Jus was deported from Guatemala as he tried to make his way to the U.S. after his father was murdered by a gang in their home town. (AP Photo/Esteban Felix)

TEGUCIGALPA, Honduras (AP) — They cannot go home again.

TEGUCIGALPA, Honduras (AP) — They cannot go home again.

For many Honduran deportees, home means a return to the brutality that sent them fleeing north in the first place.

In the neighborhoods where they grew up, corpses are dumped unceremoniously at construction sites, and carted off in body bags like loads of potatoes. Heavily armed police patrol from the back of pickup trucks, stopping to frisk pedestrians for weapons, drugs or other signs they belong to gangs.

At home, a grieving woman with a household broom tries to wash rivers of blood from the alleyway where her kin was slain.

For these deportees, home is a neighborhood ruled by murderous gangs who extort money and demand that young men join their ranks — killing those who refuse to obey.

They cannot go back home, so many seek refuge at a shelter for troubled youth in the capital, Tegucigalpa, where their stories echo each other.

Alexis, 18, arrived at the shelter two years ago after being deported from Mexico. He says gangsters had threatened him repeatedly because he wouldn’t join them, and finally his mother told him he had to run.

Salm, 14, left home after gang members threatened to kill him for refusing to join. He was in a shelter in Nicaragua for a while, but then that country sent him back.

Jus, 15, fled after his father was murdered. He was deported from Guatemala.

“I can’t go back to where I was born,” Jus says. “In any case, I don’t have any family there any longer.”

The Associated Press is not publishing the location of the refuge or the full names of its residents for safety reasons.

Many deported families no longer have a home. They sold everything to pay for a trip north and now find themselves without shelter — and the additional burden of a debt they cannot pay.

A woman named Larissa, her husband and their two children left home after the Mara Salvatrucha gang tried to recruit her 14-year-old son; when her boy refused to join, they beat him, kicking him in the face and breaking his nose.

Years earlier, her husband was shot 14 times by gang members for failing to make an extortion payment, but survived. Three of her cousins were not so lucky. They were recruited by gangs, and all died young.

“They say that those who take that path get killed,” Larissa said, speaking on condition of anonymity for safety. “That’s what happened to them.”

The family was deported from Mexico and lived with relatives in Honduras’ countryside, where Larissa’s husband worked in construction to save for another trip north. She didn’t dare move back to her hometown, El Progreso, though she did risk a visit to get a copy of the police report she had made about the gang. She hoped it will help the family gain asylum in the United States. She said they will try “when things are calm and they’re not taking kids away.”

Days later they left Honduras to try to reach the United States again.

In Tegucigalpa, the kids remain at home as long as they can. On a recent day, smiling boys with toy submachine guns play cops and gangsters, pausing when asked which side they are on: police, they say.

Today it is a game. One day, those boys may have to make a real-life decision: whether to join a gang, or to flee their homes.