PATERNA, Spain — Remedios Ferrer scrutinizes a pit where forensic archaeologists are brushing away dusty soil and white traces of quicklime, unearthing four fractured skulls amid a mass of bones and decaying clothes.

Her anarchist grandfather, Mariano Brines, was summarily executed by a firing squad in Paterna months after Gen. Francisco Franco proclaimed his victory in the 1936-39 Spanish Civil War. According to the family’s account, Brines was buried along with 99 other sympathizers of the fallen republican regime just as the dictatorship cemented its authoritarian grip.

Eight decades on, a new center-left government’s move to exhume Franco from a controversial shrine also raised attention over an unresolved issue linked to his regime — the hundreds of anonymous mass graves that testify to the dictatorship’s brutality.

Such efforts, legally active at least for the past decade, have been erratic, intermittent and led by victims’ descendants forced to seek independent, non-state funding, which has raised criticism from United Nations bodies and human rights organizations.

But for descendants of victims like Ferrer, whose parents led her to French exile as a 2-year-old and died before discovering Brines’ burial site, even the changes sought by Spain’s new Socialist government are coming too late.

“It makes me sad and angry, because it was heart-breaking for my mom, and before her for my grandmother, to know that grandpa was buried here like an animal,” said Ferrer, now 66. “They should be the ones standing here.”

Paterna is a town in the outskirts of coastal Valencia that has prospered in the shadow of an infamous execution wall still standing near the cemetery, holes of bullets still visible among flower bouquets and memorials that locals place to remember the atrocities committed at the site.

Military and civil guard firing squads shot dead at least 2,238 prisoners here according to historians’ research and the cemetery’s records. The remains are believed to have been thrown into 70 different mass graves and covered in the quicklime to seal off the site.

On Tuesday, graveyard number 112 — where two batches of 50 prisoners were inhumed months after the war ended in April 1939 — was the latest to be opened in Paterna. After days of careful digging underneath a layer of ordinary, casket-burials, piles of skeletons emerged.

Alex Calpe, one of the independent archaeologists working at the site on behalf of relatives those killed, says the experts’ work must be “thorough” because its goal is “to deliver closure to the victims’ families.”

Countrywide, the task ahead remains daunting. Mass graves are believed to hold at least 114,000 victims of the Spanish Civil War — in which half a million people are believed to have died on all sides — and the four decades of Francoism that followed.

Exhumation efforts began in earnest in 2007 with a new Historic Memory Law that condemned atrocities committed during Franco’s regime, which lasted until 1975. But the law fell short, leaving it up to local and regional governments to fund exhumations and DNA tests — which were often paid for by relatives through crowd-funding. The previous conservative administration declined to allocate any budget.

“This is not a matter of politics, whether left or right-wing this is something that should be done,” said Carmen Gomez, who leads the association of 42 relatives who pushed for the opening of graveyard number 112, ultimately paid for by a grant last year from the provincial government of Valencia.

On Tuesday, armed with the evidence of remains showing cracked bones suggesting torture or violent deaths, Gomez and Calpe’s team of archaeologists showed up in Paterna’s local courthouse to request authorities to open a criminal investigation.

The group explained that judges tend to dismiss the cases because crimes over 20 years old fall under a 1977 amnesty law that was key in ensuring the country’s peaceful transition to democracy, by protecting officials and members of Franco’s security forces from future prosecution.

Gomez says the amnesty law should be changed, or scrapped altogether, because it deprives their deceased relatives from justice. But the government has not shown any signs of wanting to revisit Franco-era judicial decisions in its efforts to amend the 2007 Historic Memory Law.

“I’m not looking for punishment for anybody, but we don’t want our relatives to remain criminals in the eyes of history,” Gomez said.

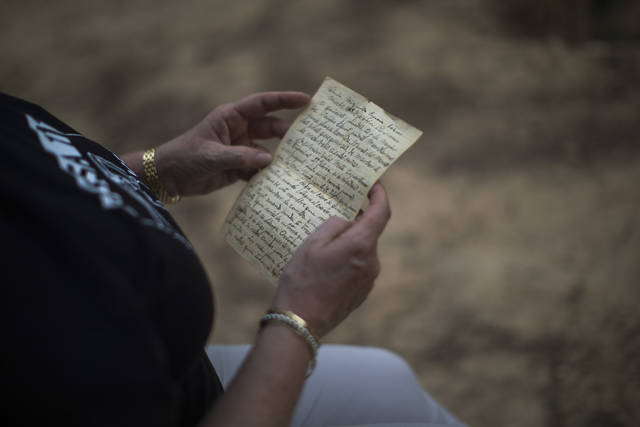

For Ferrer, the exiled relative, the unearthing of the grave where Brines is thought to be unleashed a tidal wave of hope and sadness. But she said it was a necessary step.

“This country can’t remain with such shame and darkness covered by layers of soil,” she said. “This country deserves real sunlight.”