HONOLULU — Hawaii residents emptied store shelves Wednesday, claimed the last sheets of plywood to board up windows and drained gas pumps as Hurricane Lane churned toward the state.

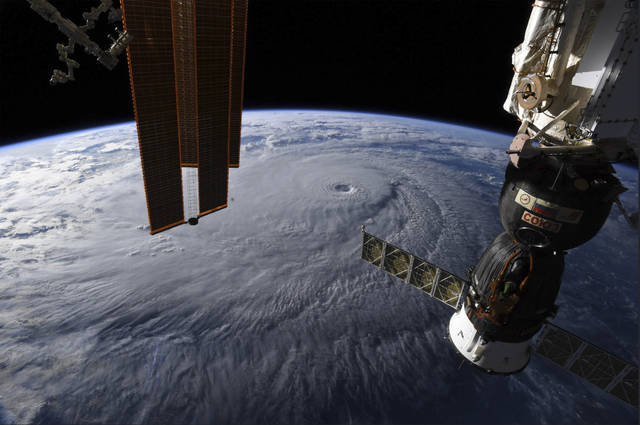

The category 4 storm could slam into the islands Thursday with winds exceeding 100 mph (161 kph), making it the most powerful storm to hit Hawaii since Hurricane Iniki in 1992.

Unlike Florida or Texas, where residents can get in their cars and drive hundreds of miles to safety, people in Hawaii are confined to the islands and can’t outrun the powerful winds and driving rain.

Instead, they must stay put and make sure they have enough supplies to outlast prolonged power outages and other potential emergencies.

“Everyone is starting to buckle down at this point,” said Christyl Nagao of Kauai. “Our families are here. We have businesses and this and that. You just have to man your fort and hold on tight.”

Living in an isolated island state also means the possibility that essential goods can’t be shipped to Hawaii if the storm shuts down ports.

“You’re stuck here and resources might not get here in time,” Nagao said.

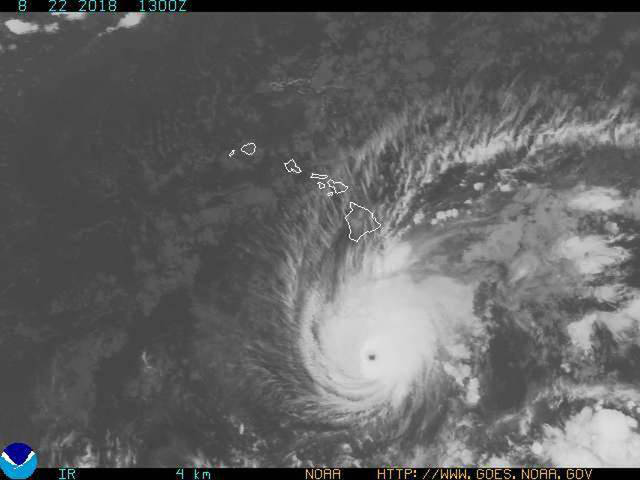

The National Weather Service said Lane is expected to make a gradual turn toward the northwest Wednesday, followed by a more northward motion into the islands on Thursday.

“The center of Lane will move very close to or over the main Hawaiian Islands from Thursday through Saturday,” the weather service said.

Public schools were closed for the rest of the week and local government workers were told to stay home unless they’re essential employees.

Shelters were being readied to open on Oahu, Maui, Molokai and Lanai. Officials said they would open shelters on other islands when needed. Officials were also working to help Hawaii’s sizeable homeless population, many of whom live near beaches and streams that could flood.

Hawaii Emergency Management Agency Administrator Tom Travis said there’s not enough shelter space statewide. He advised those who are not in flood zones to stay home.

Many residents were trying to reinforce older homes made with single-wall construction.

“We’re planning on boarding up all our windows and sliding doors,” Napua Puaoi of Wailuku, Maui, said after buying 16 pieces of plywood from Home Depot. “As soon as my husband comes home — he has all the power tools.”

Melanie Davis, who lives in a suburb outside Honolulu, said she was gathering canned food and baby formula.

“We’re getting some bags of rice and of course, some Spam,” she said of the canned lunch meat that’s popular in Hawaii.

She was organizing important documents into a folder — birth and marriage certificates, Social Security cards, insurance paperwork — and making sure her three children, all under 4, have flotation devices such as swimming vests — “just in case.”

Meteorologist Chevy Chevalier said Lane may drop to a Category 3 by Thursday afternoon but that would still be a major hurricane.

“We expect it to gradually weaken as it gets closer to the islands,” Chevalier said. “That being said, on our current forecast, as of the afternoon on Thursday, we still have it as a major hurricane.”

Puaoi said Home Depot opened at 6 a.m., and employees reported there was already a line around the building.

“We are fully stocked,” she said. “We have about nine cases of water because we’re having family stay with us as well, so one case per person.”

The U.S. Navy was moving its ships and submarines out of Hawaii. All vessels not currently undergoing maintenance were being positioned to help respond after the storm, if needed.

Navy aircraft will be kept in hangars or flown to other airfields to avoid the storm.

The central Pacific gets fewer hurricanes than other regions, with about only four or five named storms a year. Hawaii rarely gets hit. The last major storm to hit was Iniki in 1992. Others have come close in recent years.

“Winds tend to steer storms away from there,” said Princeton University climate scientist Gabe Vecchi. He also said upper level winds, called shear, tend to be strong enough to tear storms apart.

Puaoi was 12 when Iniki hit Hawaii.

“When it did happen, I just remember, pandemonium, it was all out craziness,” she said.

Some people have seen similarities in the paths of hurricanes Lane and Iniki. But Chevalier said today’s more advanced and accurate information indicates they’re completely different storms.

Nagao, who was 7 when Iniki hit, remembers that it took years before life on Kauai felt normal again.

“A lot of families didn’t prepare for it,” she said, recalling how her family had filled a boat with hundreds of gallons of water.

Hawaii has had a few hurricane scares since then. “Nothing ever happened,” Nagao said. “But this one for sure since yesterday, it started hitting home where I started having a little bit of anxiety.”

___

Associated Press writers Mark Thiessen and Dan Joling in Anchorage, Alaska, and Seth Borenstein in Washington contributed to this report.

Hopefully they will take the insurance monies and bail. Lane haas plans to clean the swamp, brushing past the other islands, which for kauai looks like a Direct hit like iwa and iniki. I pray that all the newbie transplanted will have the ohana, reconsidering our status of uninvited politicomilitary, dead set on “Killing us softly with their song”