MANAGUA, Nicaragua — The 21-year-old agricultural economics student, nearly two months pregnant, had hoped to escape Nicaragua with her boyfriend, but a police officer on a motorcycle blocked their path as they were getting into taxis with other students to go to a safe house.

Five police trucks loaded with masked and armed men dressed in civilian garb surrounded them. Uniformed officers began to search the students’ backpacks. One pulled out a blue-and-white Nicaraguan flag.

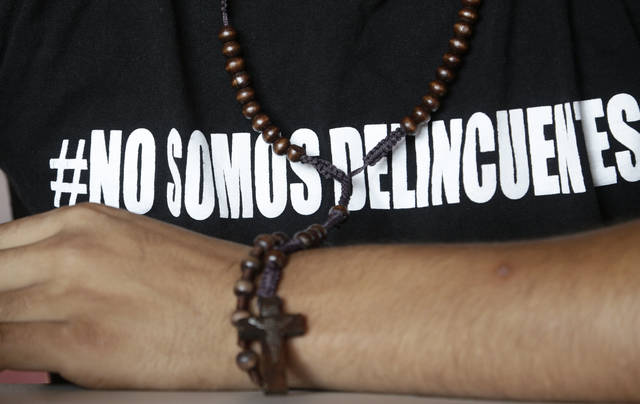

“These are the terrorists who killed our fellow police,” the officer shouted, using President Daniel Ortega’s term for those who have protested against his government since mid-April.

The young couple and their friends joined the ranks of more than 2,000 people arrested in Nicaragua in nearly four months of unrest and official crackdown. At least 400 people are believed to still be held in jails, prisons and police stations across the country and some consider them to be political prisoners, according to the non-governmental Nicaraguan Human Rights Center.

Others are held for days or weeks incommunicado, brutally interrogated to give names and threatened with terrorism charges before being released without explanation as Ortega’s government seeks to extinguish the resistance.

“I was hit in the face, slapped. They crushed my fingers, and hit me in the ribs and the stomach,” the pregnant student said. “When I was on the ground they kicked me.”

The Associated Press separately interviewed four of those arrested and released, all of whom are in hiding. They requested anonymity and asked that the location of their arrests not be identified out of fear of retaliation.

“Right now, without exaggerating, Nicaragua is a prison,” said Vilma Nunez, the human rights center’s president and a former supreme court vice president under Ortega’s first Sandinista government in 1979. She called Ortega’s systematic search for those involved in the unrest a “human hunt.”

Last week, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights said its monitoring team in Nicaragua found that “Nicaraguan authorities made numerous arbitrary detentions involving the use of force.” Detainees were abused, not informed of their rights or charges against them, no warrants were presented and their families were not told where they were held, according to the commission.

The Nicaraguan national police did not respond to a request for comment.

Ortega for weeks had denied that paramilitary squads and Sandinista youth groups that have clashed with or attacked protesters were working with the police, but when asked in a recent television interview how members of the opposition picked up by masked paramilitaries end up in jails, Ortega said: “We have volunteer police who cooperate with the police.”

He has dismissed the Organization of American States as a tool of the U.S. government and accused protesters and opponents of trying to stage a coup.

The current unrest began in April, when Ortega imposed cuts to the social security system and small protests by senior citizens were violently broken up. The protests spread and Nicaragua’s university students quickly became the vanguard of a push to oust the president who has ruled for the past decade. Students had been attacked earlier in the year while protesting the government’s slow response to a wildfire in a bio reserve and jumped at the opportunity to reassert themselves.

The student from the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua said she had belonged to the government-backed student organization, which Ortega used to maintain a foothold in universities. But when a friend was killed early in the unrest and the head of the Nicaraguan National Students Union denied that the death had occurred, the young woman joined her classmates digging in at the central Managua campus.

When paramilitaries attacked the campus in mid-July she was one of nearly 200 students driven out under heavy fire that left two people dead.

She said that when she was arrested and the flag pulled from a friend’s backpack, the masked paramilitaries threw her and the other students to the ground.

They were taken away and later made to line up in the police processing center with their hands behind their necks.

“I told (one) I was pregnant,” she said. “‘Ah,’ he says, ‘great, we’ve got a pregnant one.’”

“One of the paramilitaries came and punched me in the stomach,” she said. “‘Now we’re going to get it out of you,’ he said. ‘And you’re going to eat it alive.’”

At that point she silently prayed for divine intervention.

The men and women were separated and interrogated individually. The men were stripped naked.

A 20-year-old business administration student from the national university said he was punched in the stomach and kicked in the testicles.

“They made me spit blood,” he said.

When he nervously fumbled trying to remove a piercing from his eyebrow, a police officer ripped it out. A cigarette was put out on a tattoo on his shoulder.

“They said they were going to rape us. They said they were going to rape the girls,” he said.

The interrogations were carried out by police and masked civilians they called paramilitaries.

They were asked the same questions: Who were the student leaders? What political party was financing their movement? How much were they being paid? What weapons did they have?

A 24-year-old marketing major at the national university said a female police officer told her to tell the truth while threatening her with a knife. She slapped her face.

“They know how to hit us without leaving marks,” she said.

A 23-year-old woman who recently graduated from another university said she was slapped and hit by a rifle butt during her interrogation, but her boyfriend, who they suspected of being a leader, suffered worse abuse.

“They put a cigarette on his testicle, they burned him,” she said. “And the next day, he says they gave him an ointment, like to cover up what they had done.”

The wave of arrests has been a nightmare for the detainees’ families as well.

Maria Jose Malespin’s 27-year-old son Lester Lenin Mayorga Malespin went with a friend to Bluefields on the Caribbean coast in July to pick up a motorcycle. They were arrested at a police checkpoint on the outskirts of town.

The only clue to their whereabouts was that Lester’s wife had called him at the moment police stopped the men. He was only able to say “police” before the call ended.

For three weeks the welder was held without seeing a judge or being able to speak to his family. Malespin and her daughter-in-law flew to Bluefields to look for him only to find out after the fact that he had been transferred to Managua’s notorious El Chipote jail.

“I don’t sleep, I don’t eat, I can’t do anything,” Malespin said during her son’s captivity. “Until I see where he is, that they aren’t doing anything to him, that he’s well, healthy, I can’t relax.”

Finally on Aug. 1, he was released without explanation.

Malespin waited for him at the gate and they suffered verbal abuse from the two-dozen hardcore Sandinistas who had been posted there for weeks to intimidate families trying to get news of their detained relatives.

The son said that while in custody he was interrogated and beaten daily. They showed him photos and asked him to identify people. They asked where the weapons were.

The pregnant student’s detention lasted only five days, but the effects continued afterward.

She was taken into an interrogation room where there was a female police officer, a masked paramilitary and a civilian. They made her stand with her hands spread out on a table in front of her.

“They started to hit me more in the stomach,” she said.

They wanted to know her boyfriend’s role and why he was carrying a lot of cash. She told them they had planned to leave the country. The female officer unsatisfied with her answers cut off half of her toenail.

When she again told them she was pregnant, they told her, “the pain is what we feel fighting for the country. You all just want to see the country destroyed. You want to see our commander (Ortega) go.”

Midway through her incarceration she had started to bleed. She was interrogated and beaten again.

When the students were finally released they were warned to stay out of sight or they would be charged with terrorism.

The next day she went to a hospital. A doctor told her that there was nothing they could do.

“They told me to prepare myself for the news,” she said. “I lost my baby.”