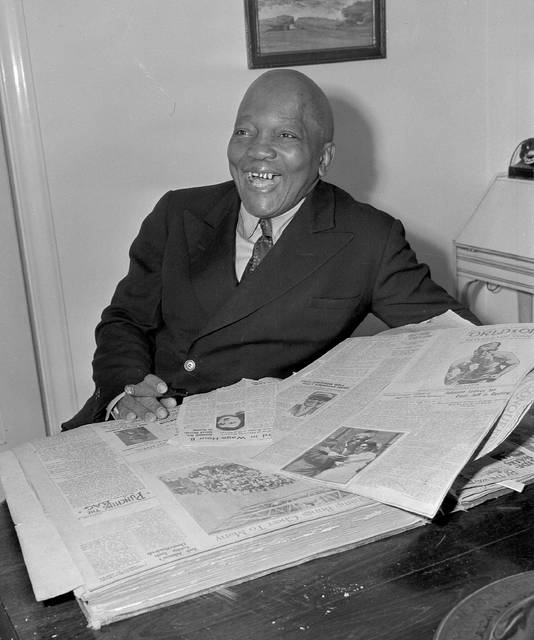

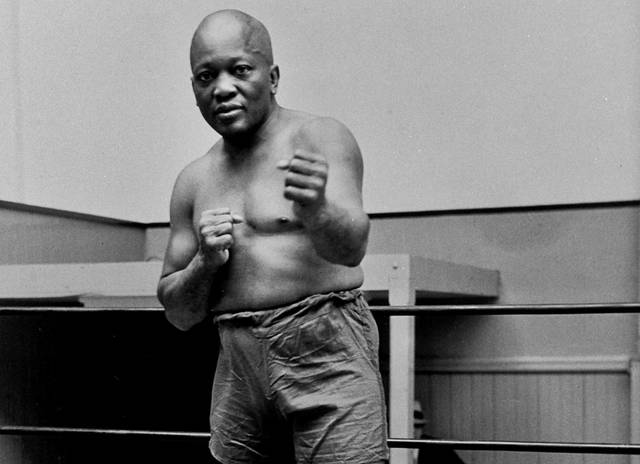

WASHINGTON — President Donald Trump on Thursday granted a rare posthumous pardon to boxing’s first black heavyweight champion, clearing Jack Johnson’s name more than 100 years after what many see as his racially-charged conviction.

“I am taking this very righteous step, I believe, to correct a wrong that occurred in our history and to honor a truly legendary boxing champion,” Trump said during an Oval Office ceremony. He was joined by WBC heavyweight champion Deontay Wilder, retired heavyweight titleholder Lennox Lewis and actor Sylvester Stallone, whom Trump credited with championing the pardon.

Trump said Johnson had served 10 months in prison “for what many view as a racially-motivated injustice.”

“It’s my honor to do it. It’s about time,” the president said.

Johnson, a prominent athlete who crossed over into popular culture decades ago with biographies, dramas and documentaries, was convicted in 1913 by an all-white jury for violating the Mann Act for traveling with his white girlfriend. That law made it illegal to transport women across state lines for “immoral” purposes.”

Trump had tweeted in late April that Stallone, a longtime friend, had brought Johnson’s story to his attention in a phone call.

“His trials and tribulations were great, his life complex and controversial. Others have looked at this over the years, most thought it would be done, but yes, I am considering a Full Pardon!” Trump wrote then.

The Oval Office ceremony was a celebratory scene, bringing together boxing greats past, present and fictional. The guests brought with them a colorful boxing championship belt, which sat front and center on the president’s Resolute Desk as he spoke. At one point, Trump jokingly asked Lewis whether he could “take Deontay in a fight” if he really started working out.

Lewis said Johnson had been an inspiration to him personally, while Stallone said Johnson had served as the basis of the character Apollo Creed in his “Rocky” films.

“This has been a long time coming,” he said.

Trump has a personal history with the sport, and hosted matches in the 1990s at his hotels.

After Johnson’s conviction, he spent seven years as a fugitive, but eventually returned to the U.S. and turned himself in. He served about a year in federal prison and was released in 1921. He died in 1946 in an auto crash.

His great-great niece, Linda E. Haywood, had pressed Trump for a posthumous pardon, and Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz., and former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, D-Nev., had promoted Johnson’s case for years.

The son of former slaves, Johnson defeated Tommy Burns for the heavyweight title in 1908 at a time when blacks and whites rarely entered the same ring. He then beat a series of “great white hopes,” culminating in 1910 with the undefeated former champion, James J. Jeffries.

McCain previously told The Associated Press that Johnson “was a boxing legend and pioneer whose career and reputation were ruined by a racially charged conviction more than a century ago.”

“Johnson’s imprisonment forced him into the shadows of bigotry and prejudice, and continues to stand as a stain on our national honor,” McCain has said.

Haywood, who joined Trump in the Oval Office, said her great-great uncle’s conviction had led her family members to live in shame of his legacy.

“For so long my family was deeply ashamed that my uncle went to prison,” she told Trump, adding that said she didn’t find they were related until she was 12 years old.

“By this pardon being issued, that would help to rewrite history and erase the shame and the humiliation that my family felt for my uncle, a great hero,” she said.

Posthumous pardons are rare, but not unprecedented.

President Bill Clinton pardoned Henry O. Flipper, the first African-American officer to lead the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry Regiment during the Civil War. President George W. Bush pardoned Charles Winters, an American volunteer in the Arab-Israeli War convicted of violating the U.S. Neutrality Acts in 1949.

Haywood had wanted Barack Obama, the nation’s first black president, to pardon Johnson, but Justice Department policy says “processing posthumous pardon petitions is grounded in the belief that the time of the officials involved in the clemency process is better spent on the pardon and commutation requests of living persons.”

The Justice Department makes decisions on potential pardons through an application process and typically makes recommendations to the president. The Justice Department’s general policy is to not accept applications for posthumous pardons for federal convictions, according to the department’s website. But Trump has shown a willingness to work around the DOJ process in the past.

———

Associated Press writer Zeke Miller contributed to this report.