Lung cancer screening has proved to be stunningly unpopular. Five years after government and private insurers started paying for it, less than 2 percent of eligible current and former smokers have sought the free scans, researchers report.

The study didn’t explore why, but experts say possible explanations include worries about false alarms and follow-up tests, a doctor visit to get the scans covered, fear and denial of the consequences of smoking and little knowledge that screening exists.

“People are not aware that this is a test that can actually save lives,” said Dr. Richard Schilsky. “It’s not invasive, it’s not painful, there’s no prep, nothing has to be stuck into any body cavity,” so to see so little use “is shocking.”

Schilsky is chief medical officer of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, which released the study Wednesday in advance of the group’s meeting next month.

Lung cancer is the top cancer killer worldwide, causing 155,000 deaths in the United States each year. It’s usually found too late for treatment to succeed.

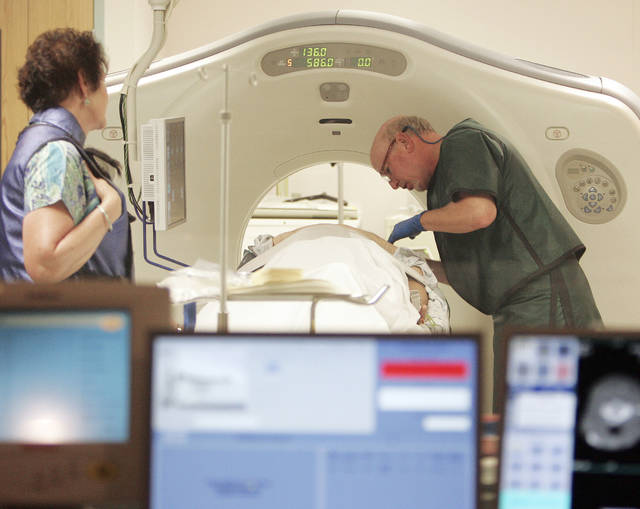

A big study found that annual low-dose CT scans, a type of X-ray, could find cases sooner and lower the risk of dying of lung cancer by 20 percent for those at highest risk. That’s people ages 55 through 79 who smoked a pack of cigarettes a day for 30 years or the equivalent, such as two packs a day for 15 years.

In 2013, a government task force and others backed screening for such folks. The scans cost $100 to $250 and are free for those who meet the criteria, but people must have a special appointment to discuss risks and benefits with a doctor.

Dr. Danh Pham at the University of Louisville in Kentucky and others got information on how many scans were done from an American College of Radiology registry of all 1,800 sites in the U.S. accredited to perform them. A federal health study was used to estimate how many current and former smokers were eligible.

The results: In 2016, less than 2 percent of 7.6 million eligible smokers were screened. Rates ranged from 1 percent in the West to 3.5 percent in the Northeast.

That’s way below the 60 percent to 80 percent rates for breast, colon or cervical cancer screening.

The study was sponsored by the Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation. One study leader has consulted for the company and other cancer drugmakers.

Mary Baroody of Alexandria, Virginia, has had several scans at MedStar Georgetown University Hospital since her husband, Michael, was diagnosed with lung cancer and successfully treated seven years ago. Both are 71 and longtime smokers who quit 15 years ago.

“I’m glad to go do it and I feel good afterward,” she said of getting screened. “You get a clean bill of health. What else could you want?”

Her husband said screening “just seems to be a no-brainer” because it can find cancer when it’s most treatable.

“I’m living proof, literally, that caught early you can do something about it,” he said.

But screening has a dark side: research shows that over three years of annual scans, 40 percent of people will have an abnormal finding that often leads to follow-up tests such as a lung biopsy, and complications of those can be fatal, said Dr. Otis Brawley, the American Cancer Society’s chief medical officer.

“I’m committed to telling people the truth and letting people decide for themselves,” Brawley said, but added that if he were a candidate for screening, “I don’t think I would do it.”

Dr. Kenneth Lin, a Georgetown family physician and former staff doctor for the government task force that advised screening, also isn’t a fan.

“There’s been a lot of skepticism” about its value, and the American Academy of Family Physicians has not endorsed it, Lin said. Many doctors feel the effort is better spent trying to get smokers to quit, he said.

———

Marilynn Marchione can be followed at http://twitter.com/MMarchioneAP

———

The Associated Press Health & Science Department receives support from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute’s Department of Science Education. The AP is solely responsible for all content.