Israel at 70: Satisfaction and grim disquiet share the stage

FILE - In this April 26, 2012 file photo, an Israeli waves towards an Israeli air force flyover during Israel’s 64th Independence Day anniversary celebrations in Tel Aviv, Israel. As Israel marks the 70th anniversary of statehood starting at sundown Wednesday, April 18, 2018, satisfaction over its successes and accomplishments share the stage with a grim disquiet over the never-ending conflict with the Palestinians, internal divisions and an uncertain place in a hostile region. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit, File)

FILE - In this April 22, 2015 file photo, school children from Belgium sit on a tank as they listen to an Israeli soldier speak about Israel’s wars, at the wall of names of fallen soldiers, at the Armored Corps memorial in Latrun. As Israel marks the 70th anniversary of statehood starting at sundown Wednesday, April 18, 2018, satisfaction over its successes and accomplishments share the stage with a grim disquiet over the never-ending conflict with the Palestinians, internal divisions and an uncertain place in a hostile region. (AP Photo/Ariel Schalit, File)

FILE - In this Dec. 6, 2017 file photo, Jerusalem’s Old City is seen through a door with the shape of the star of David. As Israel marks the 70th anniversary of statehood starting at sundown Wednesday, April 18, 2018, satisfaction over its successes and accomplishments share the stage with a grim disquiet over the never-ending conflict with the Palestinians, internal divisions and an uncertain place in a hostile region. (AP Photo/Oded Balilty, File)

This June 21, 2017 photo shows a view of Tel Aviv, Israel, As Israel marks the 70th anniversary starting at sundown Wednesday, April 18, 2018, satisfaction over its successes and accomplishments share the stage with a grim disquiet over the never-ending conflict with the Palestinians, internal divisions and an uncertain place in a hostile region. (AP Photo/Sebastian Scheiner)

FILE - In this Jan. 11, 2009 file photo, Israeli soldiers chant slogans after a briefing before entering Gaza on a combat mission at the Israel-Gaza Border. As Israel marks the 70th anniversary of statehood starting at sundown Wednesday, April 18, 2018, satisfaction over its successes and accomplishments share the stage with a grim disquiet over the never-ending conflict with the Palestinians, internal divisions and an uncertain place in a hostile region. (AP Photo/Sebastian Scheiner, File)

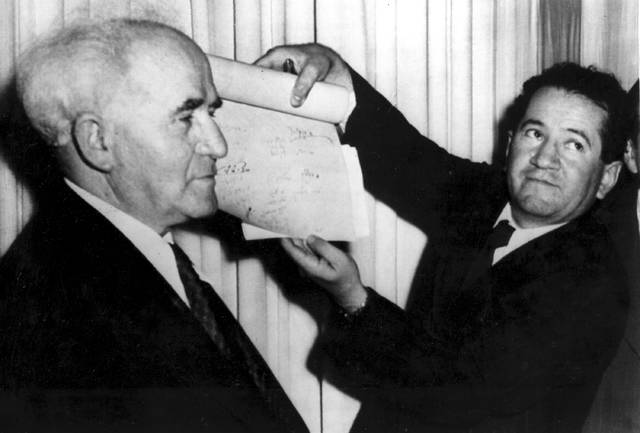

FILE - In this May 14, 1948 file photo, an official shows the signed document which proclaims the establishment of the new Jewish state of Israel declared by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion in Tel Aviv, Israel. As Israel marks the 70th anniversary of statehood starting at sundown Wednesday, April 18, 2018, satisfaction over its successes and accomplishments share the stage with a grim disquiet over the never-ending conflict with the Palestinians, internal divisions and an uncertain place in a hostile region. (AP Photo, File)

JERUSALEM — Is Israel a success as it turns 70? As Israelis commemorate the milestone this week, satisfaction and a grim disquiet share the stage.

JERUSALEM — Is Israel a success as it turns 70? As Israelis commemorate the milestone this week, satisfaction and a grim disquiet share the stage.

It has a standard of living that rivals Western Europe, though it lacks significant natural resources. It can boast of scientific achievements and military and technological clout beyond its modest size. It controls most of biblical Israel, and despite widespread criticism of its policies toward the Palestinians, it has cultivated good diplomatic ties with most of the world.

But it’s also a country that is weary from decades of conflict with the Palestinians. It is riven by religious, ethnic and economic divisions. It is still seeking recognition in a region that has not fully come to terms with the presence of a Jewish state.

Its founding declaration offers it as a “light unto the nations,” but it still is regularly accused of war crimes against Palestinians, millions of whom it has controlled for decades without the right to vote. There is no end in sight to its occupation of the West Bank, or to its crippling blockade of Hamas-ruled Gaza.

The grand peace hopes of the 1990s have mostly evaporated. Israel still feels endangered, with well-armed adversaries calling for its destruction and no permanent borders. Israelis are fretting over the possibility of war with archenemy Iran, which has a military presence in neighboring Syria.

Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, despite winning three elections since 2009, is reviled by many and faces corruption scandals.

A look at Israel at 70:

WEALTH AND ECONOMIC INEQUALITY

Fueled by a vibrant high-tech sector, Israel’s per capita GDP of almost $40,000 ranks with Italy and South Korea, and is within reach of Britain and France.

But it also suffers from one of the highest levels of inequality in the developed world, and poverty is especially prevalent among its Arabs and ultra-Orthodox Jews.

These two sectors, at nearly a third of the population and growing, risk dragging down the rest of the economy.

PUNCHING ABOVE ITS WEIGHT

For a country of just under 9 million, Israel has enjoyed surprising success. It counts eight living Nobel winners among its citizens and has helped give the world instant messaging, Intel chips and smart, autonomous vehicles. High-tech units in the military have made Israel a global cybersecurity powerhouse.

It is in a small club of nations to have launched a satellite, and is widely believed to be among an even smaller group with nuclear weapons, although the government won’t confirm it. Israel has one of the world’s strongest air forces.

It has won European basketball championships and song contests, and hit shows like “Homeland,” ”In Treatment” and “Fauda” are Israeli creations. Last year’s blockbuster “Wonder Woman” — the highest-grossing live-action movie directed by a woman — starred Israeli actress Gal Gadot.

FORGING A NATIONAL IDENTITY

Despite decades of development, Israel is still working at forging a national identity.

Over a century ago, Zionists in Europe saw the Jews as a nation, not just a religion. Persecution in Europe, culminating in the Holocaust, sent European Jews pouring into the Holy Land.

Soon after Israel’s establishment in 1948, they were joined by immigrants from countries like Morocco, Yemen, Iraq and Iran.

These Middle Eastern, or Mizrahi, Jews had little in common with their European counterparts. They were poorer, more religious and often targets of discrimination. Three generations of integration and intermarriage have blurred the distinctions, but gaps remain.

Arrivals from the former Soviet Union and Ethiopia have made Israel even more diverse, yet the different communities still often keep to themselves.

The entire arrangement can seem an affront to the founding idea of the Jews as a nation — yet it is also a rare feat that all of these have been forged into a Hebrew-speaking population with considerable national pride.

Still, antipathy exists along cultural lines: Many Europeans, still said to account for perhaps half the Jews in Israel, cannot stand the popular Arabic-style “Mizrahi music” that in earlier days was suppressed; Moroccan-descended Culture Minister Miri Regev once boasted she does not read Chekhov.

Meanwhile, nationalist lawmakers push legislation that would define Israel as the Jewish nation-state. These initiatives have faltered so far amid criticism that they would discriminate against the Arab minority of about one in five citizens.

DISAGREEMENTS OVER JUDAISM

After 70 years, the place of Judaism in the Jewish state is unclear.

Most Israelis are either secular or mildly religious. Yet the devout ultra-Orthodox, about 10 percent of the population, wield disproportionate influence because right-wing coalitions never have been able to muster a majority without them.

They have used their political power to shut down much of the country on Saturdays, the Jewish day of rest; obtain exemptions from compulsory military service; and gain a monopoly overseeing rituals like weddings and funerals. Their strict rules have upset the secular majority, but attempts at change frequently result in violent protests.

The issue of religion has also affected relations with U.S. Jews — the largest Jewish community outside Israel and a key base of support. Israel’s Orthodox establishment repeatedly has sought to prevent inroads made by the liberal streams of Judaism popular in the U.S. Last year, it blocked plans to allow egalitarian prayer at Jerusalem’s Western Wall.

Such moves have created a sense that liberal American Jews are unwelcome. They also have been disenchanted by Israeli policies toward the Palestinians. American Jews tend to be liberal and support the Democratic Party, while Netanyahu boasts close ties with President Donald Trump.

RELATIONS WITH ARAB WORLD

After Israel declared independence, its Arab neighbors attacked it. And even after the watershed 1967 Mideast war, in which Israel captured parts of Syria, Jordan and Egypt, the Arab world refused to engage.

That began to change with the 1979 peace agreement with Egypt, Israel’s first with an Arab country. Jordan followed in 1994, after Israel reached an interim peace deal with the Palestine Liberation Organization. Meanwhile, Netanyahu strengthened ties with countries like India, China and Russia.

He often boasts of covert ties with moderate Arab countries — presumably Saudi Arabia and other Gulf nations that share Israel’s concerns about Iran. Saudi Arabia now allows flights between Israel and India to use its airspace. But without resolution of the Palestinian issue, formal relations remain elusive.

PALESTINIAN ENTANGLEMENT

The euphoria that accompanied the interim peace accords of the mid-1990s was short-lived.

The sides established an autonomous “Palestinian Authority” with limited powers on islands of territory but were never able to complete a final deal, due to deep disagreements and repeated violence that killed thousands. Israel’s relations with the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank are poor; its relations with Gaza’s militant Hamas rulers, who seized the territory from the Palestinian Authority in 2007, are hostile.

Israel has faced heavy criticism and war crimes allegations for high civilian casualties in Gaza — most recently with the deaths of over two dozen Palestinians in border protests. Israel and Hamas have fought three wars. Hamas, which is committed to Israel’s destruction, has repeatedly fired rockets at Israel, with Israel accusing its leaders of using civilians as cover for attacks.

Despite the autonomy arrangement, Israel has effective control in the West Bank over 2.5 million Palestinians who are left without voting rights, while it has expanded Jewish settlements in the same territory. That has drawn international condemnation and comparisons to apartheid in South Africa.

For years, it seemed that Israel would agree to a Palestinian state next door in order to preserve its status as a democracy with a Jewish majority. But after failed talks, Israel’s current hard-line government opposes the very idea of negotiations. Opponents consider this a suicidal path.

If things continue this way, a fateful decision awaits: Give Palestinians citizenship in a single state, and end Israel’s status as a Jewish-majority country; or maintain a two-tiered system, with a disenfranchised Palestinian population that could no longer credibly claim to be a democracy.