PARKLAND, Fla. — Under the unforgiving Florida sun, the stuffed animals along the makeshift memorial are beginning to fade. The prayer candles have melted, and the roses have withered.

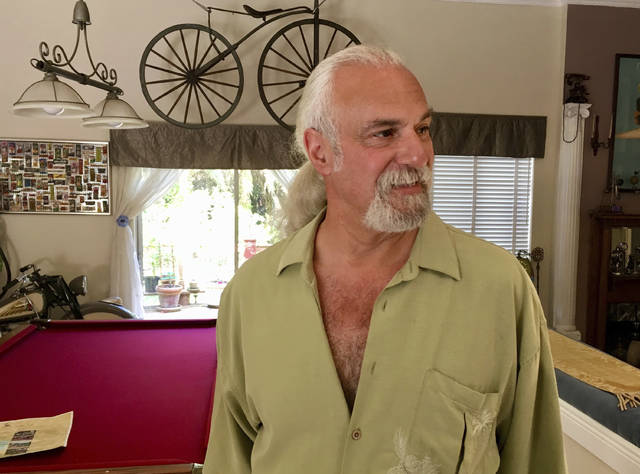

Now it’s time to collect, archive and preserve the mementos that honor the 17 students and faculty who were killed Feb. 14 at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School. The grim assignment falls to Parkland city historian Jeff Schwartz, who has already heard from people associated with other mass shootings, telling him to collect the items with “some degree of speed.”

“Objects could fade, get corroded, bug infested. And we want to be able to preserve all this,” said Schwartz, president of Parkland Historical Society.

After these tragic events, archivists face the task of documenting mementos by cleaning, photographing and storing them for future display.

Virginia Tech University digitized and created an online archive following the 2007 mass shooting there. After the 2013 Boston marathon bombing, Boston stored the gifts and letters in boxes and uploaded them online. Newtown was flooded with tens of thousands of teddy bears to honor the 26 victims of Sandy Hook Elementary School’s shooting. Families agreed to donate the toys to children in Afghanistan, Haiti and other countries, and the town kept handmade crafts and letters for a collection.

Less than two days after the Stoneman Douglas shooting, Schwartz got a call from close friend Ken Cutler, who sits on the Parkland city commission. Cutler told Schwartz to involve the historical society’s board members and to instruct his archivist to save newspaper clippings and videos.

“Obviously, it ripped out the heart of everyone,” Cutler said of the shooting. He is married to teacher at Stoneman Douglas.

Schwartz is forming a committee to gather and classify thousands of objects. His plan is to eventually display some at the library or at a museum the city has been envisioning next to an Indian burial site discovered in 1959. Families will be able to take any objects they want “for their own personal needs,” Schwartz said.

Several gun control banners will be preserved to show the students’ almost immediate reaction to the national debate. One read “Now is the time” and shows an AR-15 behind a prohibition sign. Another sign said: “Time for better gun laws” and stands near a table filled with glass jar candleholders with Catholic saints and icons known among Hispanic churchgoers such as “Our Lady of Guadalupe.”

Historians and archivists from other mass shooting locales such as Las Vegas and Orlando have called Schwartz to offer advice. The bedroom city of Parkland already has a connection to Orlando’s effort to honor its mass shooting victims. A well-known pizza restaurateur in Parkland is the brother of the owner of the Pulse nightclub, where a gunman killed 49 people in June 2016. The Parkland pizza shop, 3 miles (5 kilometers) away from the high school, has raised funds for the foundation to build a permanent museum and memorial for the Orlando victims.

In Parkland, superintendent for Broward County Schools Robert Runcie promises a memorial as well and the demolition of the three-story building where the shooting happened.

Fred Guttenberg, the father of Jaime, a 14-year-old girl who was killed in the attack, said it moves him to see the cheese crackers, puffs and Parmesan cheese that her friends left.

“Everyone knew that my daughter loved cheese and she specifically loved Parmesan cheese. Those were the people that loved her and knew her,” he said.

Although Guttenberg is more focused on advocating for gun control, he said the size of the shrines sends a message.

“It is people’s way of saying we can’t forget those who lost their lives. We have to remember the massive way in which this happened,” he said.