WASHINGTON — A divided Congress barreled toward a possible election-year government shutdown Thursday, facing showdown votes in the House and Senate to keep federal offices open and hundreds of thousands of workers on the job.

Weeks of argument over immigration, big spending and more remained unresolved, and Republican leaders were straining to win passage of stopgap legislation that would stave off a shutdown until Feb. 16 to give bargainers more time. But success wasn’t assured in the House, and odds were rising against approval by the Senate.

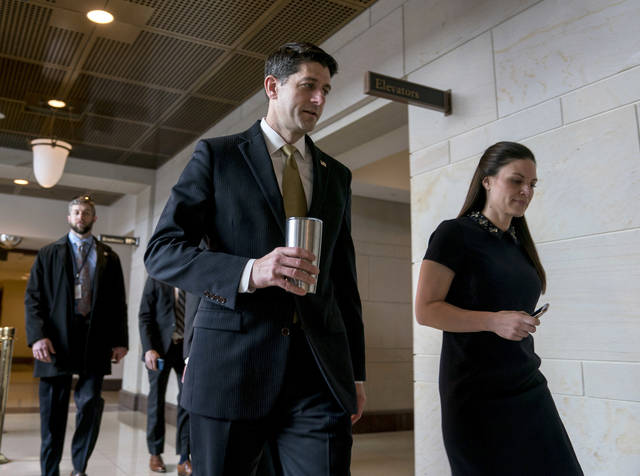

“We’re doing fine,” Republican House Speaker Paul Ryan of Wisconsin said of the bill heading for a vote in his chamber Thursday night. “I have confidence we’ll pass this.”

Even so, most Democrats were ready to oppose the legislation, and GOP conservatives were threatening to defect as well. Even if the measure survives in the House, strong Democratic opposition and uncertain backing by Republicans have dimmed its prospects in the Senate. The GOP controls the Senate 51-49 but will need at least 60 votes — meaning a large block of Democrats — to muscle the measure to passage over Democratic delaying tactics.

Even before the pivotal votes, Republicans were all but daring Democrats to scuttle the bill and force a shutdown because of immigration. They said that would hurt Democratic senators seeking re-election in 10 states that President Donald Trump carried in 2016.

Trump himself weighed in from Pennsylvania, where he flew to help a GOP candidate in a special congressional election.

“I really believe the Democrats want a shutdown to get off the subject of the tax cuts because they’re doing so well,” he said.

Democrats said Republicans would be faulted because they control Congress and the White House.

“You have the leverage. Get this done,” said House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi of California.

If the current measure fails, the next steps are unclear.

Barring a last-minute pact between the two parties on spending and immigration disputes that have raged for months, lawmakers said a measure financing agencies for just several days was possible to build pressure on negotiators to craft a deal. Also imaginable: lawmakers working over the weekend with a shutdown underway — watched by a public that has demonstrated it has abhorred such standoffs in the past.

Shadowing everything is this November’s elections. Trump’s historically poor popularity and a string of Democratic special election victories have fueled that party’s hopes of capturing control of the House and perhaps the Senate.

As he’s done since taking office a year ago, Trump was dominating and confusing the jousting, at times to the detriment of his own party. He tweeted that the month-long funding measure should not contain money for a children’s health insurance program — funds his administration has expressly supported — then the White House quickly said he indeed supports the legislation.

Congress must act by midnight Friday or the government will begin immediately locking its doors. Though the impact would initially be spotty — since most agencies would be closed until Monday — the story would be certain to dominate weekend news coverage, and each party would be gambling the public would blame the other.

In the event of a shutdown, food inspections and other vital services would continue, as would Social Security, other federal benefit programs and most military operations.

Hoping to garner more votes, Republicans added language providing six years of financing for the widely popular Children’s Health Insurance Program and delaying some taxes imposed by President Barack Obama’s health care law. The children’s health program serves nearly 9 million low-income children, and some states have come close to exhausting their funds.

But Pelosi compared the GOP bill to “having a bowl of doggy-doo and adding a cherry on top and calling it a chocolate sundae.”

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., taunted Democrats, saying, “My friends on the other side of the aisle do not oppose a single thing in this bill” and “can’t possibly explain” their opposition to voters.

Most Democrats remained opposed anyway, though saying they’d relent if there also was a deal to protect around 700,000 immigrants from deportation who arrived in the U.S. as children and now are here illegally. Trump has ended an Obama-era program providing those protections and given Congress until March to restore them.

Republicans were demanding that a separate budget bill financing government for the rest of this year include big boosts for the military, and they accused Democrats of imperiling Pentagon funding. Democrats were insisting on equally large increases for domestic programs for opioid treatment and veterans — efforts that many in the GOP also back.

While that tradeoff seemed achievable, it was the immigration dispute that loomed as the biggest hurdle, and Democrats were trying to use the need to keep government financed as leverage.

“If this bill passes, there’ll be no incentive to negotiate, and we’ll be right back here in a month with the same problems at our feet,” said Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer, D-N.Y.

Talks among top lawmakers and White House officials were moving slowly on an immigration package. Trump and Republicans want it to include money for the president’s promised wall along the Mexican border and other security measures.

Both parties faced cross-currents.

Some conservatives were balking, including members of the hard-right House Freedom Caucus. They were demanding more military spending and a promise from GOP leaders for a House vote on an immigration bill that’s far more restrictive than bipartisan measures that emerged in Congress.

Asked if he was being pressured by top Republicans to back the current short-term bill, Freedom Caucus Chairman Mark Meadows, R-N.C., said, “I don’t get squeezed. I squeeze others.”

———

AP reporters Jill Colvin, Marcy Gordon, Matthew Daly and Kevin Freking contributed.