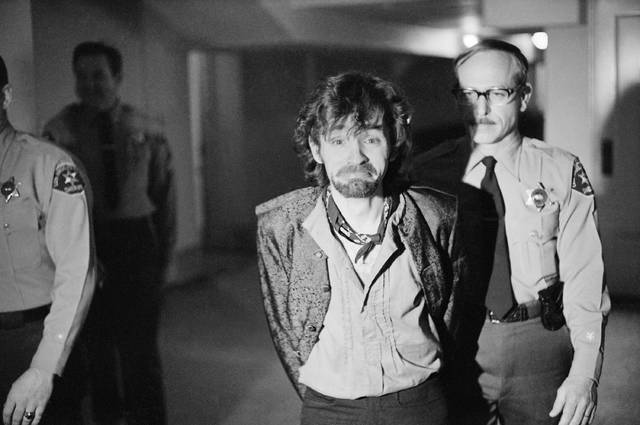

LOS ANGELES — The first time I saw Charles Manson being led into a courtroom in 1969 at the old Los Angeles Hall of Justice, I was shocked — not because of the mythology that preceded him, but because of just how small he was.

The cult leader, accused of the most notorious murders in decades, arrived amid stories of mystical powers and hypnotic eyes. Now, he was shuffling down a hallway in handcuffs, wearing fringed buckskins, surrounded by deputies.

At just over 5-foot-3, Manson was not much taller than me. His shaggy brown hair hung across his face, and he appeared dazed by the hysteria surrounding him.

Photo crews galloped down the hallway, jockeying so fast to get near him that they knocked a water fountain off the wall, flooding the corridor.

“This is crazy,” I said to another reporter. Little did I know how crazy it would become.

The gruesome murders of actress Sharon Tate and six others had stunned the world — a celebrity case like no other that plunged me into the world of high-profile trials that would become my professional calling. The Manson case shadowed my life for nearly a half-century as I covered parole hearings and anniversaries and saw a new generation become transfixed by the horror.

To this day, the name Manson can make people shudder as they recall the cult leader who ordered the killings of a group of Hollywood’s beautiful people, as well as husband and wife Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, who were slain across town from Tate’s elegant home.

The trial of Manson and three female followers lasted from late 1969 into 1971, a surreal spectacle punctuated with grotesque images of death, bloody scrawlings and tales of a “family” of disaffected youths living in a backwater commune.

The aura of celebrity permeated the case. Tate’s husband was the movie director Roman Polanski, and Manson had hung out on the fringes of the music business.

The focus was squarely on “Charlie” and the extraordinary power he exerted over his followers, leading them into a world of sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll and, ultimately, murder.

On the witness stand, his young followers spoke of orgies presided over by Manson — designed to rid them of society’s conventions — and the use of hallucinogenic drugs to break down their resistance to his ersatz philosophy.

He had delusions of being a rock star and a fascination with the Beatles song “Helter Skelter,” which the killers scrawled in blood on the walls of Tate’s home. It was later adopted as the title of a best-selling book on the trial by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi.

Manson was an ex-con who had spent most of his life in prison. He held sway over his mostly teenage devotees with a promise of acceptance they had not found at home or in the counterculture havens that dotted 1960s America. They were special, he told them.

As a short man in prison, he said he learned to survive by telling people what they wanted to hear about themselves — the same technique he used with his followers.

The case played out well before televised court proceedings and tabloid TV. Most of the courtroom photos were in black and white, and there was minimal TV footage of the defendants.

Inside the courtroom, spectators sometimes had LSD flashbacks and were dragged out shouting. Outside, a ragtag band of women camped on the sidewalk day and night. They were Manson’s “family,” who worshipped him and compared him to Jesus. They became a tourist attraction and were always available for media interviews.

One day, they showed up in saffron robes threatening to immolate themselves if Manson was convicted, just as nuns in Vietnam had done in protest of the war.

As I watched from my front-row seat, Manson took the stand outside the jury’s presence to explain himself in a riveting monologue.

“These children that come at you with knives, they are your children,” he pronounced. “You taught them. I didn’t teach them. I just tried to help them stand up. … I am just a reflection of every one of you.”

In the next breath, he uttered his most quoted line: “I have killed no one, and I have ordered no one to be killed.”

It was a lie, and everyone knew it. But the jury was not in the courtroom, and he refused to repeat his words for them.

In court, Manson choreographed a spectacle that included his three co-defendants jumping to their feet and singing songs mocking the judge. At one point, he propelled himself across the counsel table, brandishing a pencil and shouting at the judge: “Someone should cut your head off, old man.”

He and the three women were so disruptive that they sometimes were exiled to an adjoining room, where they listened to an audio feed of the trial.

When then-U.S. President Richard Nixon declared Manson was guilty “directly or indirectly,” Manson somehow obtained a copy of a newspaper headlining Nixon’s remarks and flashed it to the jury, trying to provoke a mistrial. He failed.

Manson’s power over the women was obvious. When he showed up with an “X” carved in his forehead saying he was “Xed out of society,” the women mutilated their own foreheads the next day. He later changed his carving to a swastika.

When the women eventually confessed to murder, they absolved him of any blame. Their lawyers said they had been brainwashed.

All four were convicted of multiple murders and sentenced to die in the gas chamber, but their sentences were commuted to life in prison when the death penalty was briefly outlawed in California.

That was the prelude to years of parole hearings for the four. Manson rarely appeared, sending word that prison was his home and he didn’t want to get out.

For the band of journalists who covered the Manson trial, those 10 months felt like a plunge into horror beyond comparison. If the story had been put forward as a Hollywood script, no one would have bought it. It was just too unbelievable.

———

Deutsch covered high-profile trials for The Associated Press for 46 years.