ATMORE, Ala. (AP) — The convicted killer of a police officer used his final moments before being put to death to curse at the state of Alabama, raising his middle fingers in defiance at the start of a lethal injection his lawyers described as inhumanely painful.

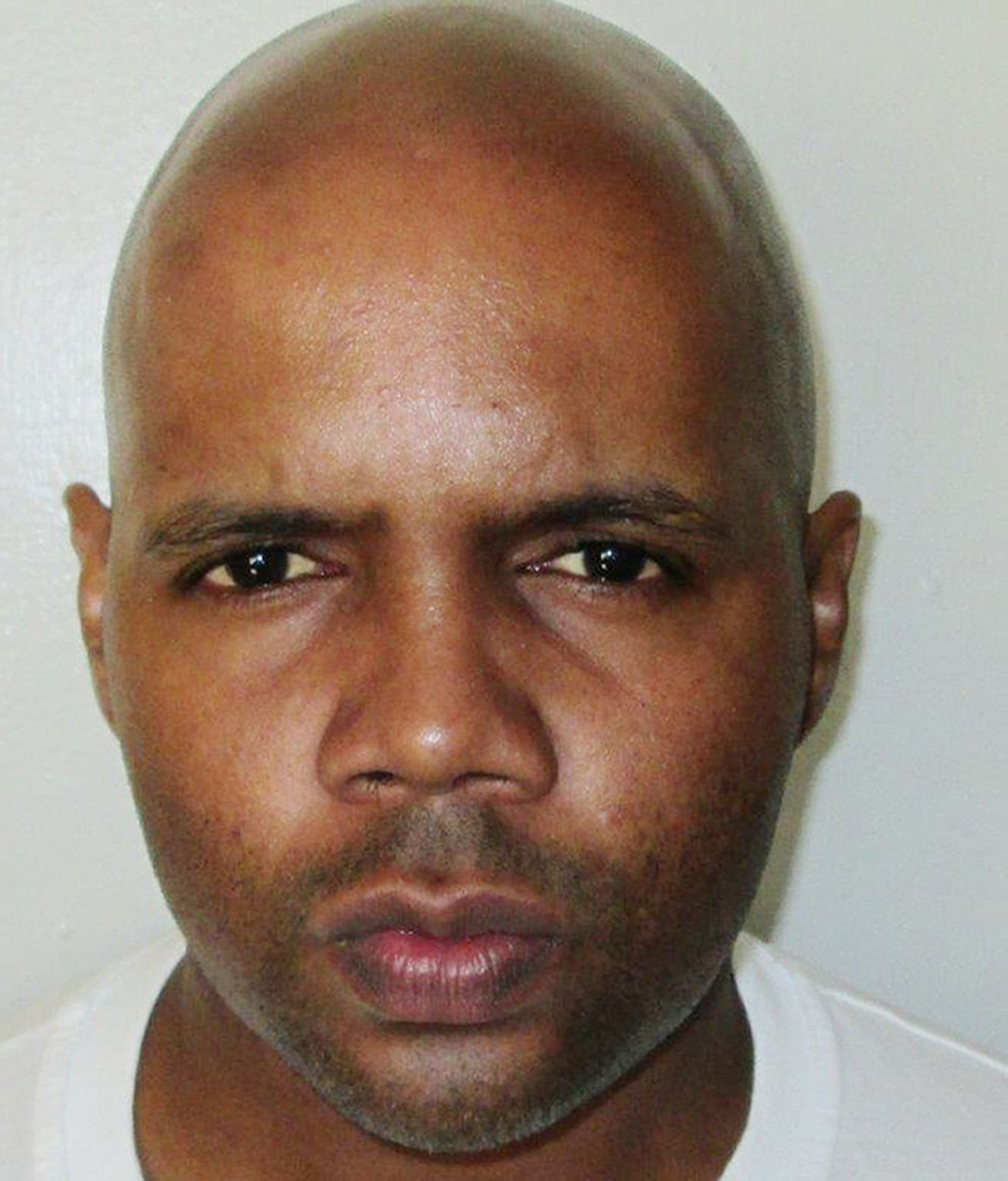

Torrey Twane McNabb, 40, was executed Thursday for the 1997 slaying of Montgomery police officer Anderson Gordon. McNabb shot Gordon five times as the officer sat in his patrol car after arriving at a traffic accident McNabb caused while fleeing a bail bondsman.

McNabb’s attorney said Friday that his movements during the middle of the execution, that included moving his arm and rolling his head back and forth after a consciousness check, showed problems with the sedative used by the state. Alabama Department of Corrections Commissioner Jeff Dunn said he was confident that McNabb was unconscious and the movements were involuntary.

While strapped to the gurney in the death chamber at a southwest Alabama prison, McNabb used his final words to lash out with an obscenity at the state executing him.

“Mom, Sis, look at my eyes. I got no tears in my eyes. I’m unafraid. … To the state of Alabama, I hate you … I hate you. I hate you,” McNabb said as the warden held a microphone for him to speak.

After the warden left the room to start the intravenous flow of lethal injection drugs from an adjoining control room, McNabb raised his arms as far as he could and extended the middle fingers of both hands, keeping them in the air for several minutes until his hands dropped as he showed signs of drowsiness.

McNabb was one of several inmates in an ongoing lawsuit arguing that the sedative midazolam does not reliably render a person unconscious before subsequent drugs stop the lungs and heart. In the Alabama procedure, a prison guard performs a consciousness check by pinching the inmate’s arm, saying his name and touching his eyelid to see if the inmate reacts before the killing drugs are administered.

McNabb appeared to react by flicking his hand upward after a first consciousness check. He was given a second check about 18 minutes into the procedure. Prison officials in the control room, unseen by witnesses, then administered the next two drugs.

Authorities won’t say exactly when the drugs begin flowing into an inmate’s body, but four minutes after the second check, McNabb raised his arm and rolled his head back and forth with a grimace on his face, and then fell still.

McNabb’s family members and attorneys who witnessed the execution expressed concerns to each other that he was still conscious during the lethal injection. “He’s going to wake up,” one of his relatives whispered.

“His execution last night again shows that despite the State’s claims, Midazolam works exactly the way we have said it does in our challenge to its use. It does not relieve pain and only sedates to a level where pain is still felt, but the person cannot react. It creates an illusion of anesthesia, nothing more,” McNabb’s attorneys said in a statement issued Friday.

Dunn said he is confident that McNabb was unconscious. Alabama has carried out five executions using midazolam.

“I’m confident he was more than unconscious at that point. Involuntarily movement is not uncommon. That’s how I would characterize it,” Dunn said.

The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals last month ruled that a judge prematurely dismissed inmates’ midazolam lawsuit, in which McNabb was a plaintiff, and ordered more proceedings. John Palombi, an attorney for McNabb, said he wants to find out “more about the events of last night in the time leading up to the trial on the constitutionality of the protocol.”

Gordon’s relatives in a statement read after the execution that the 30-year-old officer — known as “Brother” — was devoted to his two children and his work as a police officer before his life was taken on Sept. 24, 1997.

“Over 20 years ago, we lost a companion, a father, a brother and friend who only wanted to make a difference in his community,” the statement read. “Although, the wounds of having a family member murdered can never be healed, through this tragedy, the Gordon family has remained strong and will continue to be resilient.”