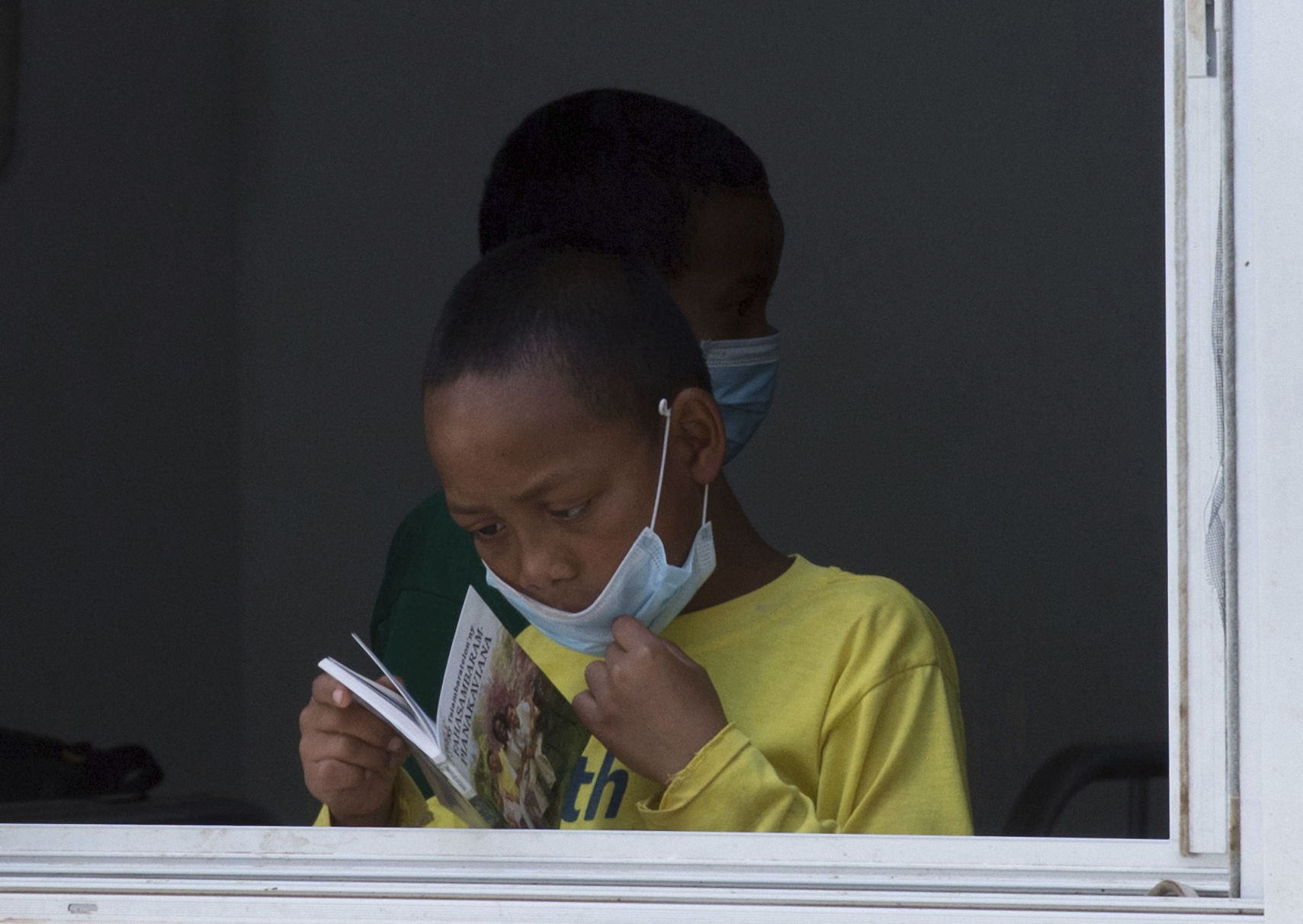

ANTANANARIVO, Madagascar (AP) — As plague cases rose last week in Madagascar’s capital, many city dwellers panicked. They waited in long lines for antibiotics at pharmacies and reached through bus windows to buy masks from street vendors. Schools have been

ANTANANARIVO, Madagascar (AP) — As plague cases rose last week in Madagascar’s capital, many city dwellers panicked. They waited in long lines for antibiotics at pharmacies and reached through bus windows to buy masks from street vendors. Schools have been canceled, and public gatherings are banned.

The plague outbreak has killed 63 people in the Indian Ocean island nation, Madagascar’s government says. For the first time, the disease long seen in the country’s remote areas is largely concentrated in its two largest cities, Antananarivo and Toamasina.

Global health officials have responded quickly. The World Health Organization, criticized for its slow response to the 2014 Ebola epidemic in West Africa, has released $1.5 million and sent plague specialists and epidemiologists. The Red Cross is sending its first-ever plague treatment center to Madagascar.

On Wednesday, Madagascar’s minister of public health rallied doctors and paramedics in a packed auditorium at the country’s main hospital, saying they’re not allowed to go on vacation.

“Let’s be strong, because it’s only us. We’re at the front, like the military,” Mamy Lalatiana Andriamanarivo said. The outbreak could continue until the end of infection season in April, experts warn.

Madagascar has about 400 plague cases per year, or more than half of the world’s total, according to a 2016 World Health Organization report. Usually, they are cases of bubonic plague in the rural highlands. Bubonic plague is carried by rats and spread to humans through flea bites. It is fatal about the half the time, if untreated.

Most of the cases in the current outbreak are pneumonic plague, a more virulent form that spreads through coughing, sneezing or spitting and is almost always fatal if untreated. In some cases, it can kill within 24 hours. Like the bubonic form, it can be treated with common antibiotics if caught in time.

The WHO calls plague a “disease of poverty” caused in part by unsanitary living conditions. Madagascar has a per capita GDP of about $400, and national programs to control the disease have been “hampered by operational and management difficulties,” according to a report by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

But the airborne pneumonic plague, which accounts for about 75 percent of cases in the current outbreak, makes no class distinctions.

“Normally, the people who catch the plague are dirty people who live in poor areas, but in this case we find the well-to-do, the directors, the professors, people in every place in society, catching the disease,” said Dr. Manitra Rakotoarivony, Madagascar’s director of health promotion.

The current outbreak began in August, earlier than usual, when a 31-year-old man who had spent time in a village in the central highlands, Ankazobe, traveled by bush taxi to the east coast, unaware that he had the plague. He died en route and was buried without any safety precautions in Toamasina. Four people in contact with him also died.

Residents of the capital began to relax in recent days amid the global response to the outbreak, but the disease remains a serious threat with the number of new cases per day remaining steady.

Madagascar has fought the disease for more than a century. It was introduced to the island in 1898 when steamships from India brought rats infected with the bacteria that causes the disease. The plague nearly disappeared from Madagascar for 60 years, starting in 1930, but re-emerged in recent decades.

The black rats that carry the disease in the highlands have gradually developed resistance to it. Unsafe burial practices that involve touching corpses are another reason the disease spreads, according to a 2015 study by scientists at the Pasteur Institute in Madagascar.

The outbreak has alarmed neighboring countries. A 34-year-old man in another Indian Ocean island nation, the Seychelles, contracted the pneumonic plague while in Madagascar. He was treated in his own country and no longer has symptoms.

It was the first-ever plague case in the Seychelles, said the country’s public health commissioner, Dr. Jude Gedeon. Another Seychellois, a 49-year-old basketball coach, died of the plague last month while in Antananarivo for a tournament.

Seychelles authorities have established a plague isolation ward and announced that schools will be closed through Tuesday. Foreign travelers who have recently visited Madagascar are not being allowed into the country.

While the WHO says the risk of the epidemic spreading beyond the region is very low and does not advise restrictions on travel to Madagascar, Air Seychelles has canceled all flights to and from the island until further notice.

“The situation is still not under control in Madagascar,” Gedeon said.