The spate of arrests, details of under-the-table bribes to teenagers and the expected downfall of one of the sport’s best-known coaches has triggered uncomfortable soul-searching among the institutions at the heart of college basketball, including internal reviews by more than

The spate of arrests, details of under-the-table bribes to teenagers and the expected downfall of one of the sport’s best-known coaches has triggered uncomfortable soul-searching among the institutions at the heart of college basketball, including internal reviews by more than two dozen schools of their own prominent programs.

At stake is the future of a business that, over the span of 22 years ending in 2032, will produce $19.6 billion in TV money for the NCAA Tournament, known to the public, simply, as March Madness.

The NCAA distributes those billions to its conferences and universities, and that figure doesn’t include the millions splashed around by shoe companies, who play an outsized role in the success of the programs and the careers of some of their top players.

More than two dozen universities with major hoops programs — including Louisville, where Hall of Fame coach Rick Pitino is in the process of being fired after 16 seasons — have responded to news of the sport’s bribery scandal by conducting internal reviews of their compliance operations.

The Associated Press asked 84 schools, including all the nation’s power programs, and six top conferences about their response to the arrests that upended college hoops mere days before practices for the 2017-18 season began around the country.

Of 63 schools that responded, 28 said the probe prompted their own internal reviews. So did the Pac-12 Conference, which formed a task force to dive into the culture and issues of recruiting.

Among the schools reviewing their programs are Arizona, Auburn, Oklahoma State and Southern California; each had assistant coaches arrested as part of the sting.

The list also includes Alabama, where a review led to the resignation of basketball administrator Kobie Baker but unearthed no NCAA violations, according to school officials.

A representative from one school, St. Johns, told AP the NCAA directed all Division I programs to examine their programs for potential rules violations after the federal complaints were filed. The NCAA declined to comment when asked about that specific directive.

But last week, the NCAA formed a fact-finding commission to be led by former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, with results expected in April — right around the time the NCAA Tournament comes to an end.

“My only piece of advice (to young players), don’t let the process ruin you because we will. I blame myself,” said Tom Izzo of Michigan State, one of the schools conducting a review.

Izzo is convinced players’ circles grow too large as they near the big-time and fill up with too many people with different agendas.

But in an illustration of wide-ranging perceptions of the issue, Michigan State’s cross-state rival, Michigan, said it isn’t conducting an internal review and its coach, John Beilein, said “I don’t think the sky is falling in college basketball.”

“I think that there’s certainly some rogue coaches,” Beilein said. “How many? Maybe I’ll be proven wrong, but I can’t believe there’s too much of that going out there.”

Michigan, 34 other schools and the Big East Conference said they were not specifically responding to the federal probe. But many of the “no” responses came with the caveat that the school’s athletic department is always reviewing its compliance.

Four conferences and 21 schools declined to respond to the AP’s survey, including one university that declined to respond on the record but acknowledged privately that it was reviewing its program because of the probe.

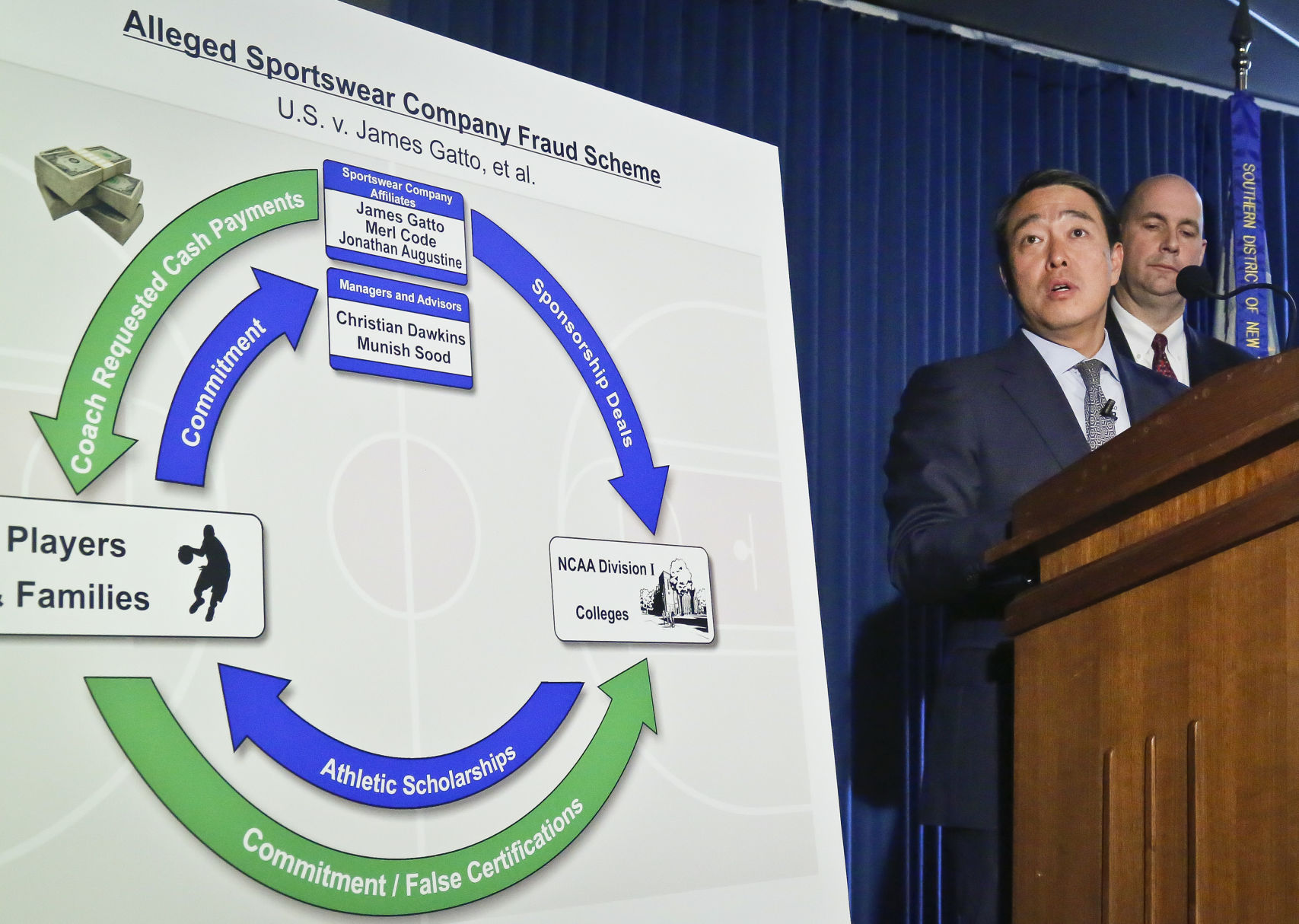

The vast majority of schools surveyed have shoe deals with Nike, Adidas or Under Armour. A top Adidas marketing executive was among the 10 people arrested, after authorities spent two years untangling schemes, often bankrolled with money from the apparel companies, to steer future NBA players toward particular sports agents and financial advisers. No players were accused of doing anything illegal, but any recruits found taking any improper benefits could lose eligibility to play.

In many corners, the arrests have been portrayed as the government’s response to activities that have long been viewed as business-as-usual in big-time hoops — a long-awaited reckoning with problems the NCAA has been unwilling or unable to rein in.

An announcement Friday by the NCAA that a seven-year-long investigation into academic fraud at North Carolina would result in no sanctions for the Tar Heels did nothing to promote confidence in the body tasked with keeping its sports clean.

The AP also asked universities if they had been contacted by federal or state law enforcement. Only the schools involved in the federal complaints acknowledged being contacted.

That doesn’t mean more isn’t coming. Prosecutors have made clear the probe could widen in scope as the investigation continues.

“I’d say most people agree that this is the tip of the iceberg,” said John Tauer, the coach at St. Thomas in Minnesota, which has won two Division III titles this decade. “Over the next six months to a year, a lot more chips are going to fall, and you’d have to think that schools that aren’t diligent right now could end up paying dearly.”

Tauer, who doubles as a social psychology professor specializing in issues of sports in society, spends a lot of time wrestling with the NCAA rulebook. His task isn’t as high-stakes, though, because scholarship money and big-time shoe deals are essentially nonexistent in Division III.

“As an educator and a coach, you’re certainly disappointed but not shocked to know this kind of thing goes on,” Tauer said. “You hear rumors and stories of things that go on in the underworld of recruiting. You always hope they’re not true, but you probably know, deep down…”

Utah coach Larry Krystkowiak told a story of losing a hard recruiting battle, and his initial reaction was “at least we didn’t cheat.”

He called it his heat-of-the-moment reaction, though he’s certainly not blind to the issues confronting his sport. When he arrived at Utah in 2011, his two guiding principles were: “We are never going to cheat,” and “We aren’t going to recruit any turds.”

“I wasn’t sure in my lifetime that we were going to see anything of this magnitude where the lid got blown off,” Krystkowiak said. “I was hopeful that at some point somebody’s going to pay the price. Now when you get the feds and the FBI involved, it takes it to a new level.”

Kansas coach Bill Self, whose school is among those conducting an internal review, said he harbors no illusions about what’s at stake.

“This is bigger than us just coming up with ideas, this is us coming up with ideas that can withhold all the headwind that’s going to be coming toward it,” Self said.

———

Nearly four dozen AP sports writers around the United States contributed to this report, including Kareem Copeland, Oskar Garcia, Jimmy Golen, Larry Lage, John Marshall, Eric Olson, Dave Skretta and Noah Trister.

———

For more AP college basketball coverage: http://collegebasketball.ap.org and http://twitter.com/AP—Top25