In the early 19th century, solar eclipses overshadowing Kauai traditionally portended dramatic, threatening changes to the island’s rulers and people. On April 12, 1810, a solar eclipse coincided with the political surrender of the Kauai kingdom by Kaumualii to Kamehameha.

In the early 19th century, solar eclipses overshadowing Kauai traditionally portended dramatic, threatening changes to the island’s rulers and people.

On April 12, 1810, a solar eclipse coincided with the political surrender of the Kauai kingdom by Kaumualii to Kamehameha.

The eclipse of Feb. 21, 1822, shadowed the sky over Kaumualii in exile in Honolulu.

And the eclipse of June 26, 1824, followed closely to the death of Kaumualii and his burial in Lahaina, Maui.

In 1819 Humehume, the son of Kaumualii sent as a child to New England to be educated, used his prediction of an eclipse over Kauai to gain favor.

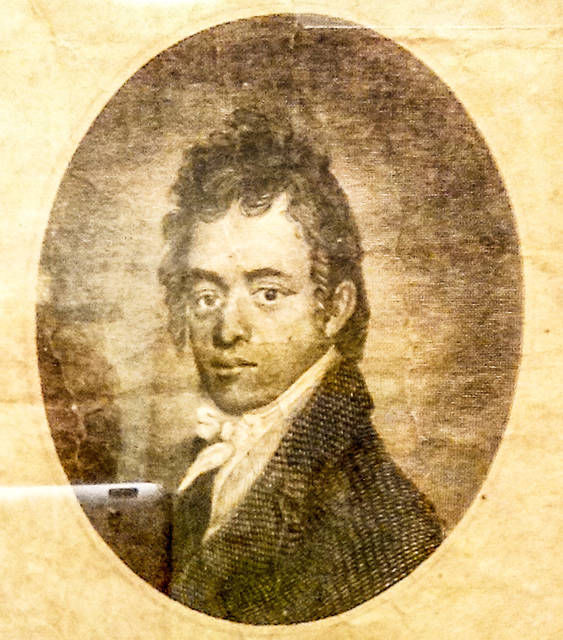

Humehume became known as George Prince Tamoree.

He studied at the Foreign Mission School in rural Cornwall, Connecticut.

He was preparing to sail to Hawaii aboard the brig Thaddeus as a companion to the pioneer American Board of Commissioners’ missionary party.

A shipment of English- language King James Bibles was being boxed up in New York City by the American Bible Society.

George learned that a special, oversized Bible was being sent with Kamehameha’s name in gold leaf on the cover.

The Kauai prince, then in his early 20s, had endured years of struggle in New England, including laboring as a child in farm fields and helping a carpenter.

He ran away to the sea as a teenager by joining the Marines during the War of 1812, and survived being run through with a sword-tipped pike during hand-to-hand combat aboard the USS Wasp.

To compensate for his lowly state, George boosted whenever possible his royal connection to his father Kaumualii, the king of Kauai.

In September 1819, George wrote a letter to the American Bible Society requesting an equally grand Bible be also sent to Kaumualii.

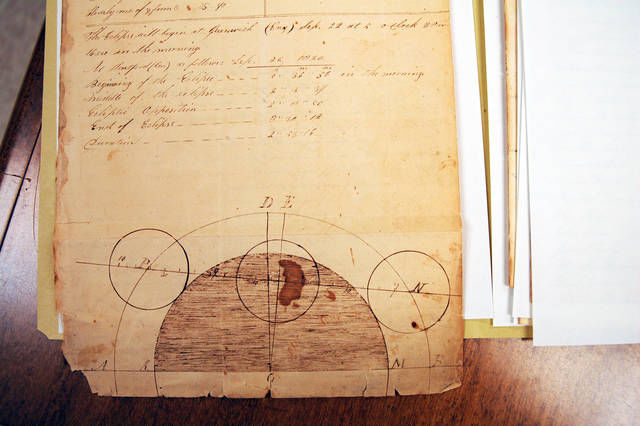

To add legitimacy to his request, George included samples of his schoolwork, in particular papers from his astronomy class at the Foreign Mission School with detailed trigonometry numbers and a drawing of a globe featuring Kauai predicting an eclipse over “Atooi” in September 1820.

These papers came to light in 2003 when I contacted the American Bible Society for information on how the Bible first came to Hawaii. I was preparing a talk on that subject to be given at the annual Hawaiian Islands Ministry conference in Honolulu. Humehume’s classwork had sat in a folder undiscovered for almost 200 years.

Humehume did return to Kauai aboard the Thaddeus in 1820.

His father, Kaumualii, was amazed and moved emotionally to see his long-lost son in the flesh, a prodigal son he had given up hope of ever seeing again, though he had sent letters home.

Missionary Samuel Whitney recorded the moment in his journal: “With an anxious heart & trembling arms, the aged Father rose to embrace his long lost son. Both were too much affected to speak.”

Kaumualii presented Captain Blanchard of the Thaddeus with a thousand dollars worth of sandalwood, he gave his son large land holdings in West Kauai and promised the missionaries his full support in setting up a mission station at Waimea.

Aboard the Thaddeus was the fancy presentation Bible that George, who again took on the name Humehume on Kauai, had requested from the American Bible Society for his father.

Kaumualii was known to read the Bible while cooling off by wading in the Waimea River with his Queen Debora Kapule.

The whereabouts of the Bible today is unknown.

By early summer 1824 another eclipse was soon to occur.

Kaumualii had died in Honolulu following his exile by Liholiho to Honolulu in 1821.

Humehume fell on hard times again by losing his royal connection.

He moved from Waimea, living in isolation at a camp he established along the coast at Wahiawa Bay, near today’s KIUC power plant at Eleele.

That summer of 1824, Sandwich Islands Mission leader Hiram Bingham, on a visit from Honolulu to the Waimea mission station, announced a mid-day solar eclipse would overshadow Waimea on June 26.

Bingham recalled in his journal: “During its progress, this phenomenon, which they had been accustomed to regard with superstitious awe and forebodings of evil, I endeavored to explain as the mere passing of the moon between us and the sun …”

The Hawaiians sought an ano (an interpretation of the eclipse from Bingham), a telling of his manao (thoughts) on what the shadow might portend.

Bingham demurred, but noted the fears of Westside Hawaiians who saw the eclipse as a foreshadowing of trouble. “Some … prognosticated war … an indication that war was desired, or was already meditated. The gloom of the moon’s shadow on the islands corresponded with the political gloom that then hung over Kauai … Others feared … destruction of the Kauai chiefs.”

These forebodings over the eclipse of June 26, 1824, came true within weeks.

In early August 1824, Humehume and a small army of disgruntled Native Hawaiians launched a surprise early-morning attack on the fort at Waimea. The attack resulted in deaths on both sides.

An army of professional soldiers under the Prime Minister and General Kalanimoku sailed from Oahu to Waimea.

Humehume collected his men and women at his stronghold along the coast at Wahiawa Bay. Kalanimoku marched up through Hanapepe to a field upland of Wahiawa Bay. There his powerful army slaughtered the rag-tag Kauai army. Bodies of the vanquished were left to be eaten by wild pigs and the ancient line of Kauai alii nui came to a humble end.

Kalanimoku spared Humehume and his wife Bette Davis Kaumualii, but exiled Humehume to Oahu. Kept under house arrest in Honolulu, Humehume died of influenza in 1826 and buried in a humble grave. The location of his burial is unknown.

•••

Chris Cook is a Kekaha resident, historian, author and former editor of The Garden Island.