LIHUE — Koloa fishermen were not happy they had to travel to Lihue on Thursday evening to discuss the future of their own fishing grounds. Tensions slowly eased at the public meeting to brainstorm solutions for protecting the marine ecosystem

LIHUE — Koloa fishermen were not happy they had to travel to Lihue on Thursday evening to discuss the future of their own fishing grounds.

Tensions slowly eased at the public meeting to brainstorm solutions for protecting the marine ecosystem at Koloa Landing and other dive sites across the island.

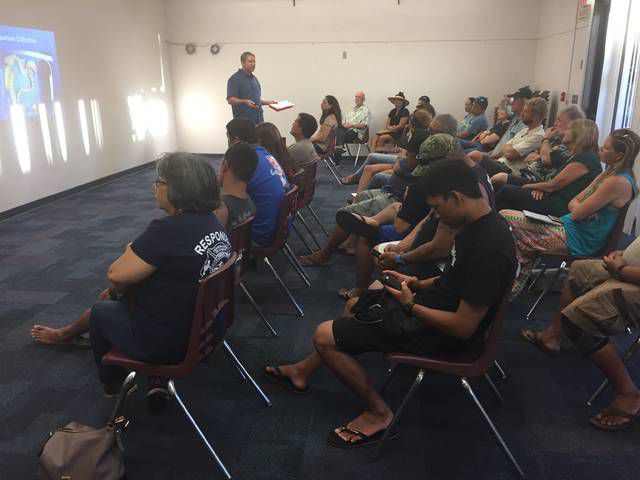

More than 30 people, including divers, fishermen, tour operators and representatives from state departments and environmental organizations, soon found a common interest in protecting Hawaii’s sea life.

The two-hour forum at the Lihue Public Library was hosted by Scott Bacon for Malama Na ‘Apapa, a nonprofit organization committed to preserving and restoring Kauai’s coral reefs.

“The recent disappearance of fish from Koloa Landing has once again piqued concern for the preservation and sustainability of marine life,” Bacon said

Numbers of unique marine species have declined at Koloa Landing during the last few years, including the Hawaiian dragon moray eel, frogfish, harlequin shrimp and colorful nudibranchs, Bacon said, an Eyes on the Reef volunteer for the Malama Na ‘Apapa Kauai Response Team.

Many factors contribute to the disappearance of threatened marine life: Coral reef health, invasive species, aquarium collectors and polluted waters, he said.

“Coral reefs are the foundation species. If coral is healthy then there’s going to be fish and all different kinds of marine life,” Bacon said. “If coral reefs disappear, then the whole thing collapses. It’s kind of a domino effect. It’s the home to all marine life.”

Some Koloa residents questioned imposing regulations that could prevent fishing to feed their families. They also expressed fears that regulated fishing areas allow invasive fish, such as the roi (peacock grouper), to dominate reef habitat without the hunting pressure.

Residents proposed spear-hunting tournaments to target the voracious eater that consumes numerous endemic fish of Hawaii.

One cause of fish disappearing at Koloa Landing in March 2016 was a collector seen harvesting dragon eels, leaf scorpion fish, and several other species for aquarium use. Although it is legal to collect these species, special permits are required to sell them. Dragon eels are sold through online aquarium shops for as much as $980.

“Harlequin shrimp used to be a consistent highlight of a dive tour at Koloa Landing. Now they are no longer around,” Bacon said. “As responsible divers, we are the strongest advocates to preserve, sustain and protect marine ecosystems. There is little protection for marine life at Kauai dive sites to keep them healthy with biodiversity.”

A representative from the state Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Aquatic Resources suggested a continued grassroots approach to publicly address concerns, as an alternative to passing rules and regulations.

The discussion produced another plan to educate divers, collectors and fishermen through signs on tour boats or near places where populations of rare endemic species have been seen.

An islandwide approach must be taken to address water quality issues that affect marine life, Bacon said. Rivers and streams collect runoff from injection wells, cesspools, septic tanks, agriculture, ranching, fertilizer, pesticides and insecticides, he said.

Waikomo Stream is the main source of harmful bacteria entering Koloa Landing, which has tested for high inshore levels of bacteria for the last eight years since Surfrider Foundation began testing there, according to its senior science adviser, Dr. Carl Berg.

“Chemicals like herbicides and pesticides entering the ocean may not kill the fish, but it may keep them from reproducing,” Berg said.

Ocean acidification is happening close to the shore because of oils in the groundwater from things like soaps, sunscreen and insect repellent, according to Berg. Human impact affects the marine ecosystem, especially at highly populated beaches where sensitive reefs get damaged from contact and sunscreens cloud the water.

All attendees agreed on the need to take action to preserve Hawaii’s most threatened marine species.