Charlie Edwards was a World War II fighter pilot

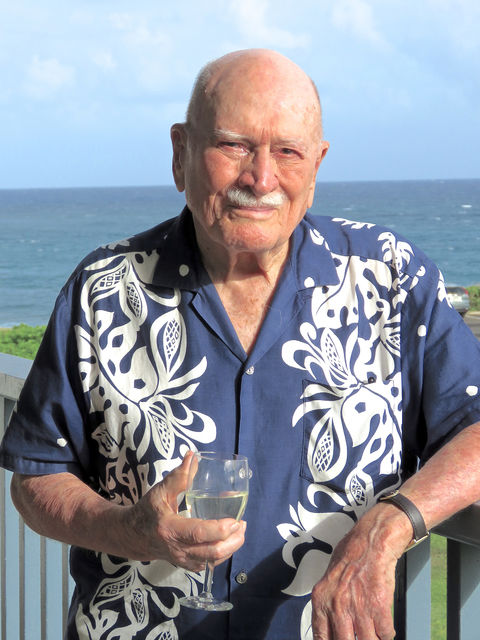

Two months shy of his 98th birthday, Charlie Edwards still has his World War II fighter pilot confidence.

“It might sound cocky, but I have never done anything in my life as well as I flew an airplane,” he said during his recent visit to Kauai. “Flying felt natural to me.”

Charlie was a member of the VC-66, a U.S. Naval Air Squadron that was stationed on Oahu, Maui and Kauai during the war. The VC-66 was awarded the Presidential Unit Citation for its collective accomplishments during battle, and Charlie received the Air Medal for his role in sinking a Japanese submarine.

Returning to Kauai’s Pacific Missile Range Facility for the first time in 72 years, Charlie was greeted by sailors and civilians. Several days later, sitting on the couch of a rented condo in Poipu, glass of wine in hand, Charlie recounted some of his most memorable moments during World War II.

As a Navy pilot, Charlie had to acquire skills that most other pilots never learn, most notably taking off from, and landing on, an aircraft carrier, an ocean-going warship that is equipped with a runway.

During the war, most land-based runways were about 1,500 feet long, but most aircraft carriers were only 1,000 feet long, leaving runway lengths of 600 feet.

But Charlie served primarily on escort carriers that were much smaller, only 400 feet in length, with only 250 feet of runway.

It took skill — and guts — to master landing in such a finite space, on a ship that was not only making forward motion, but being tossed by ocean waves.

“It had to be intuitive. There was a landing signal officer up front. He gave you a sign to cut your engine or wave off, go around and try it again,” Charlie says. “But there was a limit to how much he could control the moment that you would strike the deck, compared with how the ship was rolling or pitching in the waves.

“In rough seas, there would be a bad relationship between the moment you cut the engine and when the ship either went up or down,” he says, laughing. “Every carrier landing got your attention, you bet!”

Upon touchdown, arresting gear that included eight or nine cables tightly stretched across the deck, grabbed hold of the plane’s tailhook to rapidly decelerate it. If a pilot failed to catch one of the cables with his tailhook, the plane could slide into a barrier at the end of the runway. Beyond the barrier were parked planes or an elevator that led down to the hangar deck.

Even for trained pilots, landing on an aircraft carrier was not an easy task.

“A lot of planes missed those cables and went into the barrier,” Charlie says. “And once in awhile, somebody would go over the side.

Taking off from an aircraft carrier was also an adventure, especially when the plane needed to be catapulted. One time Charlie was catapulted off a carrier in the dark of night in the Marshall Islands.

“That was pretty scary,” he says. “They didn’t consult us pilots about how they were going to get us in the air. It depended on how much wind they had across the deck and how fast they were trying to get people into the air.”

“If you see a submarine, sink it”

As a fighter pilot, Charlie experienced being shot at by enemy planes numerous times. During training, the men had spent many hours learning aircraft recognition, so that in a tenth of a second of looking at their radar screen, they could tell how many aircraft were heading toward them, and whether they were friendly or the enemy.

But sometimes enemy fire came from submarines.

“We didn’t know one submarine from another,” he says. “We were told, ‘There are no friendly submarines out in the middle of the Pacific, so if you see a submarine, sink it.’ ”

Once, several hundred miles east of the Marshall Islands, Charlie and other Navy pilots had been instructed to go on a “hunter-killer” mission, flying solo in propeller-driven Wildcats, to seek out enemy aircraft and submarines.

“My torpedo bomber and I would fly in triangular courses. We’d go out 300 miles from the carrier, make a left, then turn back to the ship,” he says.

On April 4, 1944, during their first trip of the day, Charlie spotted a Japanese submarine that had surfaced.

“My job was to strafe the sub with armor-piercing .50 caliber rounds to keep people off the sub’s deck so they couldn’t shoot at us. I had 800 bullets to unload.”

The torpedo bomber and his aircrew also began attacking the sub, firing three pairs of rockets and two depth bombs, then Charlie dove his plane down diagonally across the submarine, firing at the ship’s conning tower. More rockets and strafing followed.

“I hung around until I was out of ammunition, and the torpedo bomber had gone home,” Charlie says. “When I left, the sub was in the water at a 45-degree angle with the bow out of the water and the stern way down. We figured it was not a good situation for them. Later, we learned that Tokyo reported that the sub was never heard from again, so they gave us the kill.”

I’ll land in deeper water

Just four months later, Charlie had another memorable experience. He had hitched a ride on a torpedo bomber to Oahu, where he was to pick up a reconditioned fighter plane and fly it back to Maui, where he was stationed.

“I checked it out visually as much as I could and took it out to the end of the runway. It sounded good to me, so I took off,” he says. “I was just past Molokai, when the engine quit, cold! There was no wind-milling of the propeller or anything. Just bang!

“Fighters have a glide ratio kind of like a red brick,” he says, laughing at the imagery. “I hit the SOS button.”

He was flying at about 500 feet, too low of an altitude to bail out, so he knew he needed to find a place to land.

What he saw was a golf course off Maui’s north shore, and envisioned landing on a lovely fairway. But when he looked down, “all I could see was trees and sand traps. I was concerned that I might flip over and be killed. I thought, ‘Nope, no, no!’ ”

As seconds ticked by, he realized his only option was to land in the ocean. He saw green, shallow water near the shore, but quickly realized if he tried to land there and the plane flipped over, he would be trapped and unable to get out.

“So I’ll land in the deeper blue water,” he thought to himself.

“From there, it was simple, no different from a carrier landing, except I did it wheels up, and I didn’t lower my tailhook. It landed nicely, a little over 150 yards from shore.”

Charlie got out of the plane and began swimming for shore.

When he was halfway in, a young Hawaiian man swam out to help him.

“He had seen me go down,” Charlie says, touched at the memory of the young man’s willingness to help him. “That fellow might still be alive. If so, I would certainly like to shake his hand.”

Minutes after swimming ashore, Charlie found himself in an ambulance, though he was perfectly fine.

From the time his motor quit to the moment he landed, was barely 40 seconds.

“Things had to be done. Decisions had to be made,” he says. “It worked out nicely.”

Charlie gives thanks to the Navy that had actually trained him and other pilots to make emergency water landings and how to get out of the plane’s cockpit in such instances. “They figured that was going to happen sooner or later, so I was prepared for it.”

The entire experience sounds like a scene from a movie, but Charlie says there was a downside: in his plane, he had been carrying a sack of mail for his squadron.

“Oh boy, I was reluctant to go back to the ready room and admit what had happened. Those letters were so precious, and there I had sank a whole bunch of them in deep water.” (A ready room is the space on an aircraft carrier where pilots stand at the ready near their planes.)

“I was greeted less than enthusiastically by my buddies when I got back,” he says. “What the Hell, it was my mail too! There had probably been a couple of letters for me.”

Don’t have to take my hat off

After the war ended, Charlie was asked to work in intelligence for the newly-formed Atomic Energy Agency in Washington, D.C., “checking what Russia was doing in the nuclear business. It was fascinating,” he says. He worked there for many years.

His beloved wife of 68 years, Marnie, with whom he raised four children, passed on four years so, so Charlie has found new things to keep himself busy.

A handful of years ago he took up archery, and has competed in national championships across the country. He is usually the only competitor in the 95 to 99 year old age bracket, so today he is the current national champion for his age group and his score remains unchallenged.

Charlie has also started writing a book, tentatively titled, “My Wonderful Life,” retracing all of his life’s adventures, for which he is truly thankful. But sometimes he finds himself facing writer’s block.

“I say to myself, ‘Come on Charlie, are you going to write a book or not?’ I want to do that while I’m still young,” he says, laughing.

Revisiting his military accomplishments for his book reminds Charlie how fortunate he was to become a fighter pilot — and how large of an impact those few years had on his entire life.

“I would not give that up. You couldn’t buy it from me. Millions of dollars wouldn’t interest me. It helped define me very much, and in a real good way,” he says. “I just don’t have to take my hat off to anybody.”