Bill Fernandez remembers Kauai in 1941

KAPAA — Bill Fernandez remembers Dec. 7, 1941 as a day of stark contrast on Kauai.

“It was one of the most beautiful Hawaiian days. The sun was shining and the ocean was calm,” he said.

His family returned from 7 a.m. mass around 9 that morning, flipped on the radio at their Kapaa home and that’s when the winds changed.

“It said, ‘We’re under attack by the Japanese and this is no drill. We’re under attack and we’re going off the air. Everybody stay indoors.’” said Fernandez. “That was the first knowledge we had of the Pearl Harbor attack on the island of Kauai.”

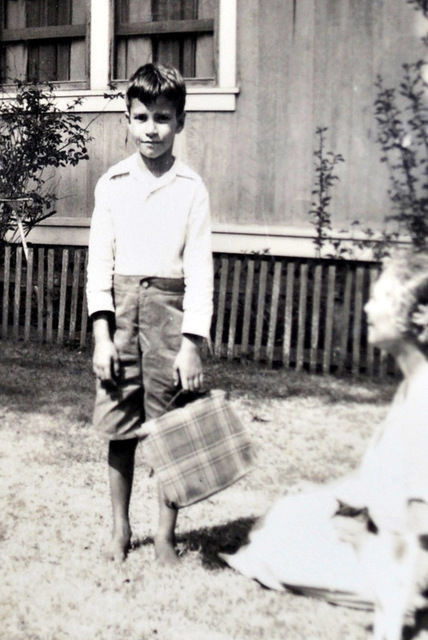

So the first thing Fernandez did — he was 10 years old at the time — is run out the door to look for the airplanes.

“My mother yelled and screamed, but that didn’t daunt me,” he said. “I had an air rifle BB gun and I went down to the beach to see if there was an invasion force coming.”

It was curiosity that drove him to the beach, he said, and throughout the years that followed that same sense of curiosity led him to make friends with many of the soldiers and National Guardsmen on Kauai.

Gas masks arrived for the people about a month after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and Fernandez said he walked to and from school daily with the mask. There were even drills at school that taught the kids how to use them in the case of a gas attack.

“We were told to go into this room with the mask on and it had been all set up for the infusion of tear gas,” he said. “They told us to go in and open it up and take a sniff or two of tear gas.”

Tear gas doesn’t kill, but it does hurt and Fernandez said he’d heard stories of the use of poison gas in the war, stories that struck fear in many people.

“It felt like, holy hell is that going to happen here,” he said.

Through the eyes of a child

“As a child, fear is momentary you’ve got that curiosity, you’re not thinking too much,” Fernandez said. “We found ways to turn the fear around and learn to relax, have a little fun with the hoop-la that was occurring.”

One example of that is the games Fernandez played with his friends in a mock-pillbox they set up about 50 feet from the beach, behind the real soldiers in their pillbox.

The kids would split themselves into two groups, an attacking force and a defending force, and the idea was to play out a battle for the pillbox using coconuts for ammunition.

“Who made the best Japanese soldiers? The Japanese kids,” Fernandez said. “We didn’t think about it, but right behind the GI’s that were defending the shore, was a small Japanese army.”

Fernandez even became a “gopher” for a company of soldiers in the Fighting 69th, buying soda, cigarettes and doughnuts for them.

“I tell the story about visiting the soldiers at night in the machine gun nests after curfew and bringing them cigarettes or whatever else they want,” Fernandez said.

Innuendo, rumor and fear

Fernandez said everyone questioned what would happen if a battle landed on Kauai’s shores.

An atmosphere of suspicion surrounded the island as well, especially since 40 percent of Kauai’s population was Japanese.

“It wasn’t just fear of airplanes coming down to bomb you or an attack from the ocean,” Fernandez said. “What about the people that you thought were your friends?”

The story of the Ni’ihau Incident further instilled fear into the people. Fernandez said he heard the story from some of the National Guardsmen that responded to the incident, but the rumor spread over the island.

A Japanese pilot landed a wounded plane on Ni’ihau after the Pearl Harbor attack and he was met with courtesy mixed with suspicion. He carried maps in his airplane, which were confiscated and he wanted them back.

So, the pilot convinced three Japanese people who were living on Ni’ihau — the island’s whole Japanese population — to help him get his maps back. The small group ended up kidnapping a Hawaiian man named Ben Kanahele and his wife and forcing them to lead the way to the maps.

When the pilot didn’t get his maps, he shot Kanahele three times. That triggered a fight and Kanahele’s wife took the opportunity to kill the pilot with a rock.

The Ni’ihau Incident took place from Dec. 7 to Dec. 9, 1941.

“The significance of that story is that 100 percent of the Japanese on the island of Ni’ihau had turned on the people they lived with,” Fernandez said. “That’s a heavy message to bring back, especially when 40 percent of your island are Japanese.”

Martial law and round-ups

Martial law was declared immediately on Dec. 7 and residents were given ration cards for food and gas. Curfew was set for 6 p.m. and the rules were that nobody was allowed outside of the house and no lights could be on. All weapons had to be surrendered.

“Except for my BB gun,” Fernandez said. “I kept my BB gun.”

Civil rights and the constitution went out the window and any sign of disloyalty was punished. Eventually barbed wire was installed as a barrier to the beach and the military patrolled the shorelines. Fishing was banned.

“How are you going to totally stop fishing in Hawaii,” Fernandez said. “You’d find a hole in the fence or you knew someone and there’d be an opportunity to get fish through that source.”

In addition to martial law, round-ups occurred and many Japanese Kauai residents disappeared into internment camps.

“A few days after the Pearl Harbor attack there were these men that came from Honolulu in dark suits. I still remember the dark suits,” Fernandez said. “They’d visit your Japanese friends and people you knew would start disappearing.”

The suspicion didn’t end with the person of interest, either.

“You could be guilty by association,” Fernandez said. “There was a lot of rumor and innuendo that was occurring that generated a lot of fear and intolerance.”

The rainbow in the storm

Sprinkled throughout the hardship and fear that the war brought with it, were opportunities to learn and to earn some serious cash — especially on a small island with an infusion of 15,000 soldiers.

“It stimulated the economy and everything moved out of the depression stage and into an economic boom for a while,” Fernandez said.

His father’s movie theater, The Roxy, is an example of a story that happened to many business owners on Kauai. In July of 1941, the state of the art, 1,050-seat theater was going bankrupt.

But, with the attack on Pearl Harbor and the reign of martial law the foreclosure action was suspended. Less than a year later, the theater garnered enough money to pay off the $50,000 mortgage.

“You had 15,000 soldiers camped behind Nounou Mountain, Sleeping Giant, and what are they going to do for entertainment,” he said. “The soldiers, they had money and they spent it.”

The boost was a blessing to many people on Kauai, who had been living in the conditions of the depression for the past decade.

“Nobody likes war and I wish Pearl Harbor hadn’t happened from the standpoint of all the people that died or were injured,” Fernandez said. “But, there are some good things that happened out of the war.”

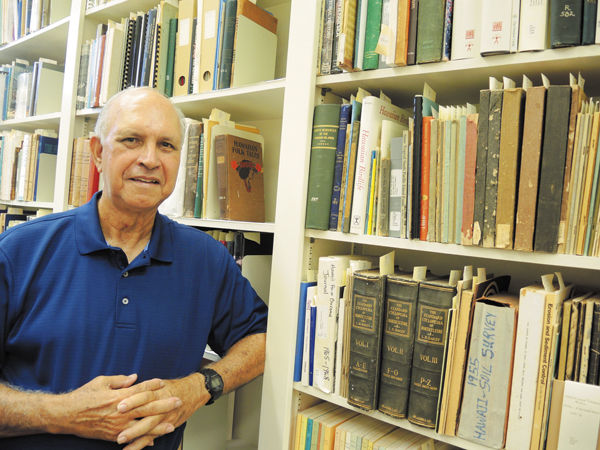

Author Bill Fernandez was born and raised in Kapaa, son of William and Agnes Fernandez who built the Roxy Theater in Kapaa in 1939. After attending Kamehameha Schools (‘49), he graduated from Stanford University and its law school. His legal career in Sunnyvale included serving on the city council and as mayor. When he retired after 20 years as judge on the Santa Clara County, California, courts, Bill eventually turned to writing memoirs of his barefoot years, then a murder mystery, and is now completing a novel set in the mid-1800s when a native Hawaiian is thrown off his farmland. Bill is half-Hawaiian, serves on the board of the Native Hawaiian Chamber of Commerce, Hale Opio, and on the State Juvenile Justice Advisory Commission, and served as president of the Kauai Historical Society. He and his wife Judith live in the house his mother bought with her pineapple cannery earnings where they count waves and write books.