A respected research professor, scientist and part-time resident has been on Kauai for several weeks coordinating the latest phase of a tuna tagging project launched on Kauai and the Big Island three years ago. Dr. Molly Lutcavage is a research

A respected research professor, scientist and part-time resident has been on Kauai for several weeks coordinating the latest phase of a tuna tagging project launched on Kauai and the Big Island three years ago.

Dr. Molly Lutcavage is a research professor at the University of Massachusetts Boston’s School for the Environment. She is also director of the Large Pelagic Research Center and is renowned for her extensive work with the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishing community.

The Ahi Satellite Tagging Project of the Pacific Island Fisheries Group is a joint venture that uses state-of-the art technology and partners fisheries organizations, policy makers and local fishermen in the effort to gather much-needed baseline data on ahi and other pelagic fish that live and migrate in waters surrounding the main Hawaiian islands and beyond.

“There’s very little information on these patterns for ahi in this region,” Lutcavage said.

“Most of PSAT or data logging tags on ahi were deployed in the eastern and western Pacific, so the Hawaiian islands remain a ‘data poor’ area as far as high-tech tag results,” she added.

Last week, six large yellowfin tuna (ahi) were tagged with pop-up satellite tags and released in waters off Kauai. If all goes well, the tags will collect data that will help identify their migration routes and behavior for one year, Lutcavage said.

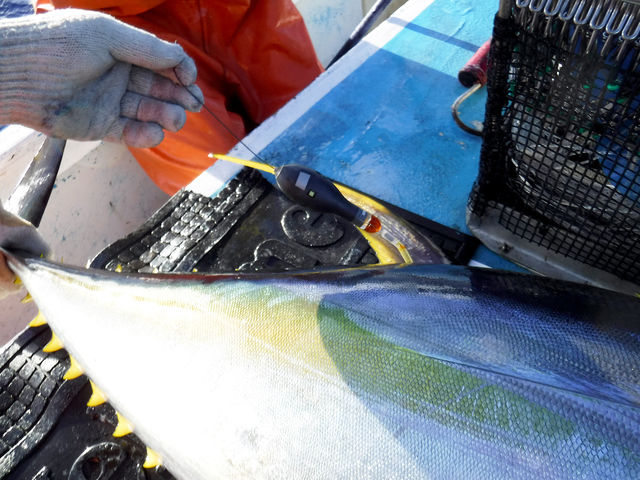

The tagging process has been used in similar projects in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Fish are brought alongside or aboard the fishing vessel and evaluated. Tags are then affixed via a dart and tether into the base of the second dorsal fin of healthy fish.

The PSATs are programmed to be released from the fish after a year, and float to the surface, where they transmit collected data to National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration satellites and Service Argos receiving stations aboard NOAA satellites.

The recorded data, depth, temperature and light levels experienced by tagged fish are obtained and then analyzed by the scientific team. Light levels are used to estimate the ahi’s daily position, based on celestial navigation techniques adjusted with ocean data from remote sensing data.

The methodology was developed by Dr. John Sibert’s lab at the University of Hawaii, Manoa. Unlike sea turtles or marine mammals, fish don’t come up to breathe, so they can’t be tracked in the same way.

As a member of the science and statistical committee of the Western Pacific Regional Fishery Council and over the past 10 years, Lutcavage felt that more research was needed on ahi. Data collected in her lab’s work with western Atlantic bluefin revealed that existing biological assumptions used in fisheries assessment were inaccurate at best, and outright wrong regarding their migration routes and spawning grounds.

Fishermen in many fishing communities have a tremendous amount of respect for Lutcavage. They know that the fishing community can only benefit from their passion to learn all they can about the resource they rely on.

“Molly is all about researching the fish,” one Kauai fishermen said. “But she is also all for the fishermen,”

This project is funded by the National Marine Fishery Service’s Co-operative Research program. The WESTPAC supplied 10 PSAT tags for tagging both yellowfin and bigeye, and LPRC donated a few extra tags for Kauai deployment.

“Tags are expensive and a sufficient number of successful, long term tag reports are needed to identify migration routes,” Lutcavage said. “We consider 25 tags a minimum to develop the most basic understanding (because tags fail at sea, and fish die or are predated upon), and ahi may have multiple migration patterns, so more tagging and financial support is needed.”

Adequate funding is always a challenge. Although there is no question the need is real and the value of data gathered for ahi is significant, the acquisition of funding is complicated by several factors. For one thing, pro-active research such as this, no matter how important, does not top the list of projects to fund. Fisheries in crisis are usually given top priority.

The length of time it takes before data can be analyzed and used is also an issue. Most agencies have a one-year funding cycle, matching the tag’s data recording mission. Ideally, the PIFG team would like to get multi-year support for projects such as this but it hasn’t happened yet, at least not for ahi.

”Yellowfin tuna are healthy and not overfished here, but we still don’t know where they are before they appear in Hawaiian waters, or where they go afterwards,” Lutcavage said. “To make sure that ahi are sustainably managed and not overfished elsewhere, we need more comprehensive information.”

“You just can’t do these kinds of projects on one-year funding without gaps,” she said. “What is needed is a dedicated, robust investment in ahi science. There has to be vision to support the basic fisheries work, whether private or federal. How can we evaluate impacts of climate change or other issues for tunas if we don’t have good baseline information? “

Lutcavage and Clay Tam, PIFG program manager, said the tag project team is grateful to the many individuals who have assisted them over the years.

Mark Oyama has helped organize and introduce Lutcavage and her team to Kauai captains. Ryan Koga, Craig Koga, and Eric Hadama fabricated the tagging poles. Other fishermen included Eric Hadama, Curtis Matsumura, Joe Koerte, Marvin Lum, Alan Horikawa and Bryan Hayashi, who helped tag in 2014 and 2015. This year, Kevin and Gavin De Silva tagged the fish.

Help from fishermen who recover the PSATs is encouraged. Tags to look for are the black bulb-like “pop up” tags. They may be attached to yellowfin or big eye tuna here. If the data logger is still attached and the fish is landed, fishermen are asked to cut off the tag and tether, record the tag number, the latitude/longitude of the catch, and the curved fork length of the fish (or estimation of length) and contact Clay Tam, (808) 284-4390 or Molly Lutcavage, (603) 767-2129 immediately.

There is a $500 reward for the return of a functioning tag (either on or off the fish) and a $200 reward for a non-functioning tag. They also want to know if you found a fish with only the tag’s tether remaining.

In addition to the PSAT tags, the plan is to put 1,100 dart tags in juvenile yellowfin and bigeye tuna to complement the satellite tagging project. Anglers will be asked to help place the tags and will be PFIG-trained and certified on how to identify species and record data.

Anyone interested in taking part in the dart tag placement or who would like to get project updates can go to the PIFG website, http://www.fishtoday.org/category/ahi-updates/

•••

Rita De Silva is a former editor of The Garden Island and a Kapaa resident.