HONOLULU — Small boat fishermen have nothing to fear from the potential expansion of Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, according to a group of Native Hawaiians. Hoku Cody, with the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Native Hawaiian Cultural Working Group, said it’s the

HONOLULU — Small boat fishermen have nothing to fear from the potential expansion of Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, according to a group of Native Hawaiians.

Hoku Cody, with the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Native Hawaiian Cultural Working Group, said it’s the longline fishing industry that would take a small hit if President Barack Obama increases the size of the monument through the Antiquities Act.

“We’re going to bat for all small boat fishermen who do access … those areas where the weather buoys are and the middle banks,” Cody said. “We’re proposing those areas be left out of the expansion.”

According to the 2015 logbook for these commercial fishing practices, only 5 percent of longline efforts are concentrated within the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

“Large-scale gathering practices like the longliners don’t align with our traditional values,” Cody said. “We want to make it clear that we are pro-small boat fishermen and we’re anti-longliners.”

The Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument began as a national wildlife refuge in 1940 under the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt and went through several phases until 2006, when President George W. Bush designated it as a national monument under the 1906 Antiquities Act.

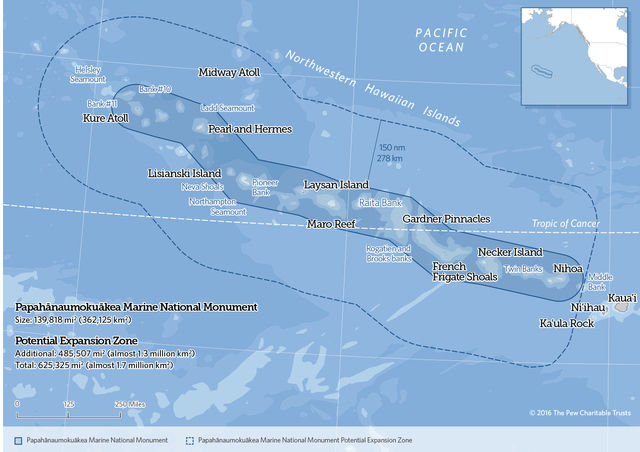

Now, on the 10-year anniversary of the monument’s establishment, a group of seven Native Hawaiians has asked Obama to extend the boundaries of Papahanaumokuakea 200 miles on all sides, except the southern boundary — to avoid cutting off access from the middle banks and the weather buoys.

The monument is 139,797 square miles. If the president declares the expansion, it would create the largest marine protected area on Earth.

Getting a seat at the table

Keola Lindsey, OHA’s Papahanaumokuakea program manager, said the creation of the monument established three levels of management. OHA has been a part of the base-level management for the past decade, but the organization wants more say in the monument.

“We’ve always pointed to the lack of Native Hawaiian representation at the senior executive board and the co-trustee level as a fundamental flaw in this unique co-management structure,” Lindsey said.

The organization has been gearing up to take on more responsibility in the monument management and is using the expansion as a way to get a seat at the table.

“We’re saying, Mr. President, as you’re considering the expansion, remember that Native Hawaiians haven’t been represented,” Lindsey said. “OHA is the only organization that serves on the management board that is excluded from the higher levels of co-management once issues are elevated.”

Culturally sacred

Cody said she sees the area as a “taproot that allows the main Hawaiian Islands to flourish,” but the significance of these waters goes beyond being the geological birthplace of the archipelago.

In Hawaiian culture, the area is where life originated and it also plays a part in the journey of death.

“We see this as an area of the gods and ancestors; it’s a place where life emerged into the world as we know it and it’s a place where spirits of our ancestors return upon passing,” said Kawika Riley, chief advocate for Office of Hawaiian Affairs. “All the life (in the area) are connected to us genealogically.”

Fern Rosenstiel, who is running for State House District 14, explained in the Hawaiian belief system, the line between cultural and biological resources is murky.

“The sharks were gods and everything was sacred,” Rosenstiel said. “There’s biological and cultural overlap.”

Cody said it’s that significance that is spurring the Native Hawaiian Cultural Working Group to action.

“This is a community-based, Hawaiian-led proposal, founded in traditional values and supported by science,” Cody said. “We’re asking for a higher standard of the way we conduct ourselves in this place.”

Scientifically significant

Papahanaumokuakea protects the habitat of more than 7,000 marine species, and scientists are finding more and more species in the area as they research the wilder parts of the seas.

“The science is very much backing the extension, it’s one of the most unique places on Earth,” said Alan Friedlander, director of the fisheries ecology research lab for the University of Hawaii and chief scientist for National Geographic’s Pristine Seas. “We’re just peeling back the first layer of the onion.”

In May, the scientific journal Marine Biodiversity published a study describing the largest sponge in the world, found at a depth of 7,000 feet within the monument. The sponge was close to 12 feet long and 7 feet wide, according to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration news release.

“The deep seas are still susceptible to potential exploitation — there’s deep sea fishing and mineral mining,” Friedlander said. “And the reefs around the world are degrading quickly. There’s very few places left that are still healthy; it’s prudent to take a precautionary approach.”

Kauai aquatic biologist Don Heacock, however, pointed out flaws with using time and resources to designate monuments while “global warming and ocean acidification is killing corals around the world.”

“It’s like Nero fiddling while Rome is burning,” Heacock said. “We’re not protecting anything by designating the monument; it’s a mirage.”

Friedlander agreed that climate change and the dying reef should be high priorities, but conservation is key, too. He pointed out the few wild and remote places left in the ocean are generally more resistant to the ocean’s changes, or are more resilient and will bounce back more rapidly.

“We should do both: redouble our efforts for marine based management and create more marine protected areas,” Friedlander said.

What’s next?

After the Jan. 29 submission letter to Obama requesting the expansion, the administration answered with a charge to show support for the idea.

That kicked off the groundwork of the effort, and brought about 50 additional people on board from across the state — mostly Native Hawaiians that have a close connection to the area, according to Sheila Sarahangi, who has been working behind the scenes as a statewide organizer.

The group also began a petition, which has garnered more than 67,000 signatures in support of the expansion, and had a May meeting with the Obama administration on Oahu to share the proposal.

Sarahangi said the group is now focused on building momentum into the September meeting of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature World Conservation Congress in Honolulu.

She said if the president does declare the expansion, the working group expects there will be a public comment period, and are “strongly advocating for a public meeting on Kauai” because of its proximity to the monument’s borders.