HANALEI — It’s the time of year when Kauai’s nocturnal seabirds start to lay their eggs. That means Kauai Endangered Seabird Recovery Project is once again out with its radar truck collecting data on the birds. The truck will be

HANALEI — It’s the time of year when Kauai’s nocturnal seabirds start to lay their eggs. That means Kauai Endangered Seabird Recovery Project is once again out with its radar truck collecting data on the birds.

The truck will be monitoring populations of ‘a‘o, or the Newell’s shearwater, and ‘ua‘u, or the Hawaiian petrel, on Kauai, said Andre Raine, KESRP project coordinator.

Field researchers will be surveying at the same 18 sites around Kauai that have been surveyed since 1993.

“We use this data to chart long-term population changes over time — which is the best islandwide measure for how populations of both the species are doing,” Raine said.

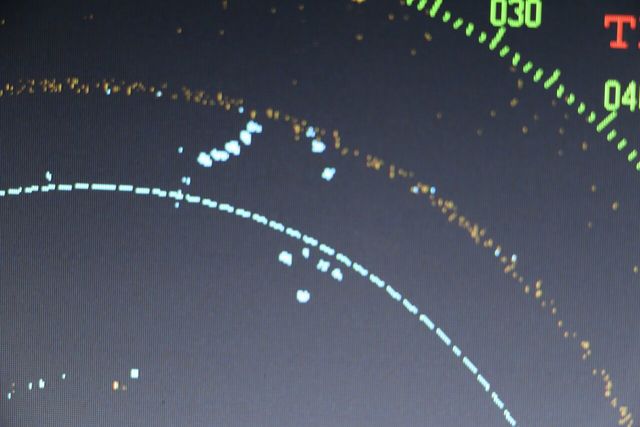

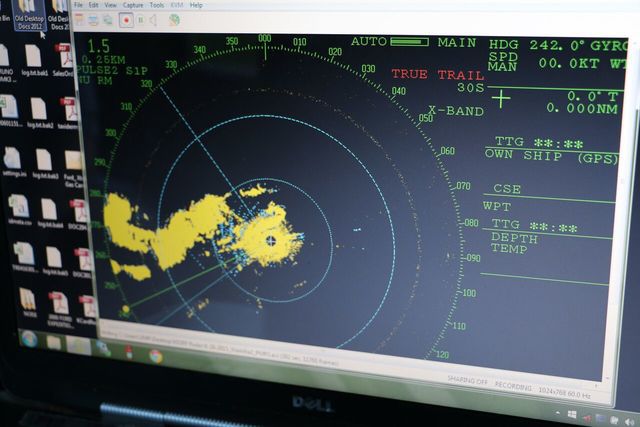

KESRP is using radar because both species of seabirds fly back to their burrows in their colonies at night, making it difficult to see them. Radar puts the birds on a screen as a series of blips.

“We use a combination of the bird’s speed, behavior and the time of night to identify the bird species,” Raine said.

He explained KESRP researchers only count targets moving faster than 30 miles per hour because that’s the typical flight speed of the two seabird species. He also said seabirds are moving in a straight line inland at the time of night when the monitoring is conducted, rather than meandering.

The time of the flight helps distinguish between the two species — ‘ua‘u fly inland earlier in the evening than the ‘a‘o.

He said the seabird radar monitoring project leaves out the band-rumped storm-petrel — the other endangered seabird within KESRP’s purview — because those colonies are in harder to reach places along the Napali Coast.

He said KESRP is monitoring storm-petrels using acoustic monitoring units, which record the nightly calls of the storm-petrels.

Raine said both the ‘a‘o and the ‘ua‘u are mainly concentrated in the northwest part of Kauai, in areas like Hono O Na Pali Natural Area Reserve, Upper Limahuli Preserve, and the large valleys of Wainiha, Lumahai and Hanalei.

Data collected from these annual radar monitoring has been useful in documenting the trends of the species’ populations, but Raine said the news they’re getting from the data isn’t necessarily good.

He said the data has shown a huge decline since the early 1990s.

“The colonies to the east and south of Kauai in particular have declined dramatically in the last 20 years, with some of them disappearing altogether,” Raine said.

He explained 90 percent of the world’s population of ‘a‘o and a significant portion of the world’s population of ‘ua‘u are concentrated on Kauai.

“They face significant threats from introduced predators, such as feral cats and rats, as well as changes in their habitats, collisions with man-made structures, and the effects of light pollution,” Raine said. “Charting their population trends helps us to understand how the birds are doing at an island level, and that information can be used to help conservation actions designed to save them.”

Radar monitoring began Wednesday and will continue through September, with the peak activity in June. The radar truck will mainly operate for the first two hours after dark to track the birds as they fly inland to their breeding colonies.

Radar will also be operated for two hours before dawn, tracking the seabirds as they head out to sea.