‘My Name is Yoshiko’

Susan Matsumoto was 10 days shy of her 20th birthday on the morning Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, plunging the United States into World War II.

In that moment, life changed for Susan, her three siblings and their parents, who had been farmworkers in rural Southern California for nearly 20 years.

Four months after the bombing, Susan’s family and 120,000 other Japanese Americans across the country, were imprisoned, perceived by the U.S. as threats to national security solely because of their Japanese ancestry.

Now 94 years old and a Kauai resident, Susan looks back at the trajectory her life took as a result of these momentous events, in her newly published memoir, “My Name is Yoshiko.” Her book title honors the name her parents gave her at birth, Yoshiko, meaning “good child” in Japanese.

Living in a horse stall

Several weeks after Pearl Harbor was bombed, Susan and her family began seeing governmental notices posted around town announcing that all persons of Japanese ancestry were being “evacuated,” and were ordered to report to a place the government called the “Santa Anita Assembly Center.”

The “assembly center,” turned out to be the Santa Anita Racetrack, where horse races were previously held.

“As we got off the bus, we saw several very tall guard towers. The entire track was surrounded by a barbed-wire fence, with about 200 soldiers with guns guarding the perimeter,” Susan says. “We were only 15 miles or so from our home, but it already felt like we had been deposited into a cruel distant world.”

Susan’s family was assigned to live in a horse stall.

“The floor was dirt and there were three cots lined up head-to-head,” she says. “We could smell the strong odor of horse manure and urine. We wondered if anyone had even tried to make the horse stalls habitable for humans. Our hearts sank.

“My father said, ‘Oh my goodness, we didn’t do anything bad.’”

For five months, Susan’s family of six lived in that one-room, dirt-floor horse stall, wondering every day how long they would be forced to stay there.

The partition that separated their stall from the family living in the stall next to them did not reach the ceiling, so there was no privacy. There was no kitchen in the horse stall, of course, and they had to use horrible communal bathrooms that also had no privacy. Some families were assigned to live out by the grandstand of the racetrack and had to sleep on mattresses filled with hay.

Despite the hardships, Susan’s family began to settle into a rhythm of tolerance.

“We became accustomed to the searchlights that swept the grounds nightly,” she says. “And we found ways to keep clean, in spite of there being only 150 showers for the whole population.

“In the evenings, some of us young people would sit in the grandstand and watch the trains going by on the tracks outside our jail. We wondered what each one was carrying: troops, war supplies or food?”

“Recently I learned that while we were living in that horse stall, my father signed up for the Fourth Registration of the Army draft, often referred to as the ‘old man’s registration,’ for men who were between 45 and 64 years old,” Susan says. “My father signed up to prove his loyalty to the United States.”

‘Gaman’

Eventually rumors began circulating among the internees at the racetrack that they would be released. Soon they learned the sobering reality: they were to remain imprisoned indefinitely, but now in a “relocation center” in Arkansas.

Loaded onto trains along with 10,000 other people from the racetrack, they were shipped for four days to Arkansas. They were ordered to keep the blinds down over their windows the entire time.

“I don’t know if this was so we could not see the outside world that we were no longer part of, or if it was to protect us from people who would not understand that the Japanese faces looking out were Americans, and not the enemy,” Susan says. Nevertheless, she peeked out of her window.

“On the second day, as we passed through Texas and several other states, I saw cotton fields after cotton fields. Small shacks dotted the landscape, and I assumed that’s where the hired farmhands lived,” she says. “The scenes made me yearn for the simpler years of my childhood. We had worked long days doing manual labor on the farm, but at least we had our freedom.”

They arrived in Rohwer, Arkansas, on Sept. 24, 1942.

“The first thing we saw was barbed-wire fences and high watchtowers, with soldiers aiming rifles at endless rows of barracks,” Susan says. “I wondered, ‘What kind of place is this?’”

It was a more permanent internment camp for U.S. residents of Japanese ancestry, consisting of 500 acres of tar-papered barracks hastily built to hold 8,000 people. Rohwer was one of 10 similar camps across the nation.

Susan’s family of six once again had to live in one room.

“Thank goodness when we arrived, we had no idea we would spend the next two years in this God-forsaken place,” she says.

To some, it may have appeared that Japanese Americans who were sent to internment camps during World War II were submissive, too obedient for their own good or simply very docile.

Susan says outward appearances were the opposite of the truth, that the Japanese concept of gaman is more accurate.

“Gaman is to remain strong in the face of adversity, regardless of how much suffering we feel,” she explains. “Gaman is enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.”

Rejoining America

After living in the Rowher internment camp for two years, Susan’s family was released, each person given $26 by the government.

“I wondered how in the world we were going to pay rent and buy food until we all found work with only $26 apiece,” she says. Her father was 67 years old by this time.

The family found work on a farm in Michigan, employed by a Japanese family that had lived in the barracks across from them in the Arkansas internment camp.

Shortly thereafter, Susan and one of her sisters were given a blessing: the opportunity to work as waitresses at Devon Gardens Tea Room, an upscale restaurant in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. The restaurant had been named by a Michigan newspaper “one of America’s most distinguished and distinctive tea rooms.”

It was at Devon Gables that the young woman who had been born with the name Yoshiko, received her English name of Susan, given by her employer. Her sister was given the name Frances.

“I think our boss gave us English names because when she started hiring Japanese workers from the relocation camps, she received many threatening letters,” Susan says. “Maybe it was a blessing that we got our English names.”

One year, Susan and Frances spent the Christmas holidays in Chicago, where they met a young Japanese American man named Tom T. Matsumoto, who was visiting friends in Chicago. Tom, who had recently completed four years of service for the U.S. Army and lived in Los Angeles, had been born and raised in the tiny town of Kekaha on the island of Kauai.

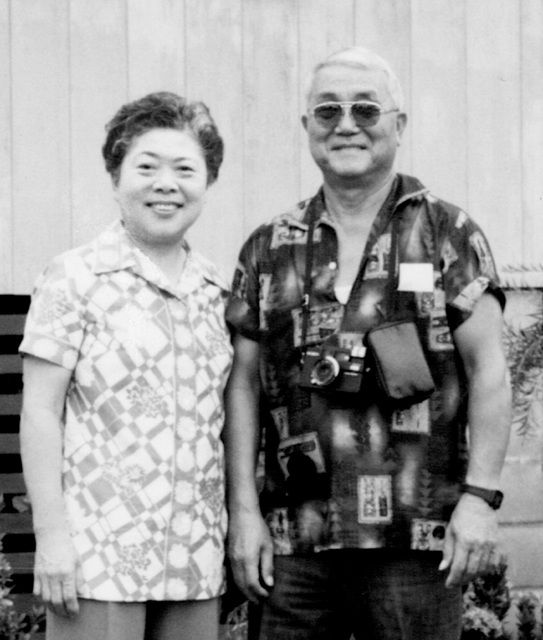

Susan and Tom became engaged and were married in 1947. After living in Chicago for 20 years, the couple relocated to Southern California for 10 years, so Tom could be closer to Hawaii. The couple retired to Kauai in 1977, where they lived in Kalaheo. Tom passed on in 2004 and Susan now lives in a retirement community on the island.

When Susan thinks back on the years that she, her family and so many others were unjustly imprisoned, she remarkably harbors no resentment. “War is war,” she says matter-of-factly.

Thought she understands why some people allowed themselves to become embittered by the entire experience, she is happy that her family chose not to hold onto any anger.

“I believe that our positive outlook enabled us to endure the years we were wrongly confined, so that once we were released, we could be happy during the rest of our lives.”

•••

Read Susan Matsumoto’s story in its entirety in her book, “My Name is Yoshiko,” available on Amazon, published by Write Path, LLC. Pamela Varma Brown is the publisher of “Kauai Stories,” “Kauai Stories 2” and “Kauai In My Heart.” Visit www.WritePath.net.