KEKAHA — Robby Kohley shone a light against the avocado-sized bird egg, illuminating its hidden contents. An embryo inside resembled a large, red spider with legs that stretched in every direction. An air cell at the shell’s apex jiggled. “This

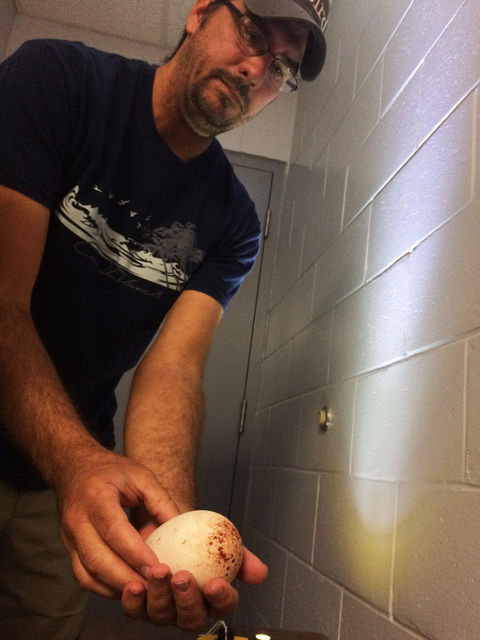

KEKAHA — Robby Kohley shone a light against the avocado-sized bird egg, illuminating its hidden contents.

An embryo inside resembled a large, red spider with legs that stretched in every direction. An air cell at the shell’s apex jiggled.

“This one’s fertile,” Kohley said. “See the spider? You can even see a tiny bit of movement in the embryo if you look really close.”

By morning’s end, two dozen Laysan albatross eggs had been candled by Kohley, an Oahu-based avian ecologist for Pacific Rim Conservation.

Twenty were fertile. One was not. Three others showed signs of infertility, but Kohley said it would be best to wait and continue to monitor the eggs for hints of life.

The eggs had been collected from nests along the runway at the Pacific Missile Range Facility at Barking Sands, a historically popular breeding spot for albatrosses. This species that spends most of its life gliding over the sea returns to land from mid-November to mid-December, during most years of its life, in order to mate, as well as lay and incubate an egg.

Almost as if drawn back by a magnetic pull, the bird returns every year to the same place.

PMRF’s runway area has swift wind conditions and wide, open topography that make for perfect albatross breeding terrain. Well, almost perfect.

The problem is that the birds pose a collision hazard in the runway zone, putting themselves, the aircraft and flight crews at risk.

So every year the eggs are collected, and those that are fertile are transported to Kauai’s North Shore, where albatrosses occupy about a 10-mile strip of coastline from Moloaa to Princeville. Scientists then identify which albatross pairs there have laid an egg that’s infertile so they can swap it out for a fertile one from PMRF.

The idea is to encourage the albatrosses, who imprint on the location of their birth colony, to adopt a safer place, away from air traffic, to call home. The species may fly more than 2,000 miles in a single stretch, and always know how to find their way back to where they came from.

All told, about 70 eggs are transported off of PMRF’s runway area annually. Eggs that can’t be placed locally on the North Shore are transported to James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge on Oahu, where Kohley works.

PMRF’s albatross program is organized by biologist Tom Savre, a Navy contractor.

“Obviously the bird doesn’t want its egg taken away — that’s a failed nest,” Savre said. “But the trade-off is that every egg we take we give to another bird that’s going to lose an egg due to infertility. Sometimes infertile eggs will explode, rotten, if the bird is still sitting on it waiting for it to hatch, not knowing that it’s no good.”

Some of the infertility on Kauai results from female-female albatross pairs. Since male albatrosses outnumber females here, a pair of females will sometimes try to incubate an egg, not knowing that it won’t hatch.

Another part of the program is the annual transport of about 200 birds from the runway area to more albatross-friendly zones on the North Shore.

“The way I see it, is that anytime there’s an albatross here on the ground at PMRF, they draw new albatross in and they start to socialize,” Savre said. “If we had people out there 24/7 and every time a bird came in we picked them up and brought them up north, we’d be even more effective. But we have been effective. The activity on the airfield is definitely decreasing.

“We have people who come and say, ‘Wow, we used to see albatrosses here all over the place. Where are all your albatrosses?’ So even without all our data, anecdotally we know it’s working.”

Following a period of decline, in part due to an illegal feather trade, the number of albatrosses across the Hawaiian Islands is rebounding. The birds, which have a 7-foot wingspan and a habit of noisily clacking their beaks open and shut, are found mainly in the uninhabited Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, as well as on Kauai, Niihau and Oahu.

Since the future of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands is uncertain due to rising sea levels, scientists are working hard to reestablish albatross colonies on higher elevations on the main Hawaiian Islands.

“The number of birds that lay an egg each season (at PMRF) is kind of holding steady right now,” Savre said. “But the one thing that’s changing is the number of new guys that are coming in. That number is increasing because there are more albatross on Kauai every year. That’s a good thing. We want more albatross, we just don’t want them here along the runway.”

On Tuesday afternoon, six albatrosses in animal carriers made their way from Kekaha to Na Aina Kai, a botanical garden with a fenced-in cliffside albatross breeding zone in Kilauea. One by one, Savre opened the door to the carriers. The birds stepped out onto a dirt pathway cloaked in needles from Cook pines.

Savre hoped the birds would stay. But he knew the great likelihood that some would make their way back to PMRF again.

Clacking beaks and bobbing necks, the birds meandered like drunkards toward the cliffside and a brilliant turquoise ocean.