Loyalty proven

As a boy growing up on the Hawaiian island of Maui, Clinton Shiraishi’s only aspirations were to become a sugar plantation laborer like his father, who had immigrated to Hawaii from Japan in 1915.

“I remember my father telling me what was good enough for him as a plantation laborer should be good enough for me,” says Clinton. “My scope was very limited at that time.”

But through a series of fortuitous events, and Clinton’s native intelligence and determination, he became a decorated World War II veteran who helped liberate the Dachau concentration camp; a successful lawyer and judge on Kauai; and in 1960, he founded one of Kauai’s first and largest real estate brokerages that is still thriving today.

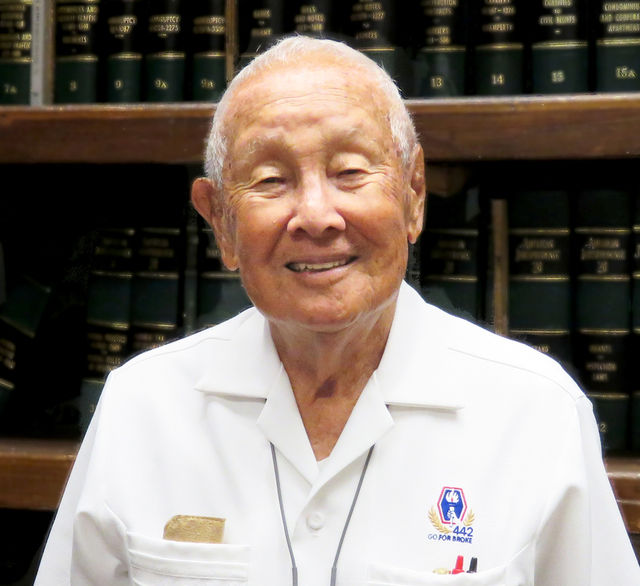

Slim and trim at 93 years old, Clinton mentions his accomplishments only when specifically asked about them, typical of his generation of Japanese-Americans who are notoriously humble. He speaks in perfectly structured sentences, with only a hint of the Pidgin accent that reflects his sugar plantation roots.

Clinton’s first inkling that there were opportunities for him beyond manual labor was as an eighth-grader, when he was sent to the school principal’s office for something he had not done.

“The principal addressed me by my Japanese name: ‘Ikuzo, you’re a smart boy. Have you ever thought about becoming a lawyer?’ Here I am, just a plain country boy. Until that day, it had never occurred to me that I would be anything but a plantation worker.”

After ninth-grade graduation, when his father wanted him to begin working for the plantation, his grandmother interceded.

“My grandmother, bless her soul, told my father that I could amount to something if I continued my schooling,” Clinton says. “So my father relented and I continued high school.”

Prove our loyalty

But life changed shortly after high school for Clinton and all Japanese-Americans, on the day that Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, plunging the United States into World War II.

“Even though I was born in America, we Japanese-Americans were looked upon with suspicion. No matter where we went, I always had the feeling that Caucasians did not fully trust us,” Clinton says. “So when the call came for volunteers to join the Army, I felt I had to volunteer to prove my loyalty to the United States.”

Clinton joined the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, comprised of Nisei, the first generation of Japanese born in America. The soldiers of the 442nd, along with the 100th Infantry Battalion, with whom they were combined, were sent to some of the bloodiest battles of the war, fought valiantly, and suffered tremendous loss of life.

With their “Go For Broke” motto, the 100th/442nd became the most highly decorated units in U.S. military history at that time, earning more than 18,000 individual decorations for bravery, including 9,500 Purple Hearts, awarded to those killed or wounded in action.

As a member of the 522nd Field Artillery Battalion (part of the 442nd), Clinton fought in the now-famous battles in the small French towns of Bruyeres and Biffontaine.

He was also part of the rescue of the “Lost Battalion,” a Texas-based unit that had been entrapped by the Germans for a week, and was running out of ammunition and food.

“It was nearing winter, very cold, we were hunkered low to the ground to stay warm,” he recalls. “When our leader said ‘Go,’ our infantry guys stood up and charged up the hillside, shouting ‘Banzai!’ and ‘Go for broke!’ It took us about a week, but we finally overcame the Germans.

“When we rescued them, the Lost Battalion was down to about maybe 200 men. But in doing so, our combat team suffered about 800 men in casualties,” Clinton says.

After the rescue of the Lost Battalion, surviving members of the 100th/442nd were ordered to assemble so the general could personally thank them for their efforts.

“When we were all gathered together, the general looked at our group and asked our commanding officer, ‘Where are the rest of the men?’ Our commanding officer sadly said, ‘Sir, you’re looking at the entire regiment. This is all that’s left.’

“So many of our boys were killed. So many badly wounded,” Clinton says. “It was a very horrendous war experience for all of us veterans.”

Clinton himself was wounded during the war, fighting near Florence, Italy, while German soldiers were firing shells at his unit.

“One of the shells struck a tree that I was under. The shell exploded and one of the shell fragments sliced through my thigh,” Clinton says. “I didn’t even know I was wounded. When I stood up, I noticed blood flowing down my trousers. The aid station people bandaged me up. The medical officer said, ‘Sergeant, you got yourself a Purple Heart.’”

Liberating Dachau

In March 1945, nearing the end of the war, Clinton and the 522nd Battalion were sent into Germany. Pulling their 105 mm Howitzers, which were cannon-like guns, with a 2½-ton truck, they moved quickly across the country, facing little resistance.

Traversing though rural, farm-like countryside, the 522nd suddenly came upon the Dachau concentration camp, having no idea what it was.

Dachau was the first German concentration camp to be built and was originally intended for political prisoners. It became the prototype for nearly 100 similar camps throughout Germany and Austria, where prisoners, primarily Jewish people, were tortured by German guards in hideous ways, their bodies incinerated in ovens built for that express purpose.

“When we came to this concentration camp, the German guards had already escaped. So one of our sergeants went up to the gate and blasted the lock with his gun, then opened the gate,” Clinton recalls.

“The prisoners, those who could walk, came out very slowly. They were emaciated,” he says. “We could see some of them, those who were too weak to walk, lying down in the snow on the ground. The Germans left them starving.

“Some of us went into the concentration camp and toward the back there was a building that looked like a warehouse,” he says. “We went inside and we saw, oh, lot of dead people. In the back, there was a large oven, still warm yet.”

The men offered their military-provided food such as canned Vienna sausage and Spam, but most of the prisoners, having been starved for years, had difficulty eating at all. To their horror, Clinton and his fellow American soldiers watched as other prisoners spotted a dead horse and cow along the road, tore off the flesh and began eating the meat raw.

“Oh, I felt so sad, I cried,” Clinton says, tearing up at the memory. “I can still see in my mind’s eye, those prisoners walking out, all skin and bones. I know some of our guys, when we talk about what we saw, we will still cry today.

“Some of the Caucasian units have gone down in history as the first ones to get to the concentration camps,” he says. “But in our case, we were the first to come to this particular camp, because it was our guy, a Japanese-American, who blasted off the lock and opened the gate.”

When the war in Europe ended, Clinton and his Hawaiian regiment-mates headed home.

“The sad part was after the war, we went to visit the parents of deceased soldiers, our friends who had been killed. I remember one who was my high school classmate,” he says. “I can still recall the tears in his mother’s eyes when we had to tell her that her only son had been killed.”

‘Lawyer more easy’

Prior to the war, while still living on Maui, Clinton had studied bookkeeping, typing and shorthand — a form of speed writing used by court reporters — so he could secure a job working in an office, rather than being a plantation laborer.

After the war, he attended Gregg College in Chicago to become a court reporter. One of his instructors suggested that Clinton visit a courthouse to watch actual trials — and court reporters — in action.

“I saw this court reporter writing down fast, 160 words per minute, and the lawyer standing up and talking. I said to myself, ‘Hey, being a lawyer more easy than being a court reporter.’”

So Clinton changed gears, enrolled in the exclusive John Marshall Law School, and graduated third in his class.

He returned to Hawaii, married a Kauai girl, and stayed with her parents on Kauai while awaiting his bar exam results. He had planned to move back to Maui to practice law, but on the day he passed the bar, the chief justice of Hawaii telephoned him.

“He said, ‘There’s a district court judge position open on Kauai. I’d like to appoint you to that position.’ I said, ‘Sir, I just got my license. If you think I’m good enough, I’ll accept the position.’”

Clinton served as a judge on Kauai, both in Koloa on the island’s South Shore, and in Lihue, the government seat of the island.

While handling deeds and other documentation, Clinton noticed that his real estate clients were making much more money selling one property than he made doing multiple transactions.

“So I formed Kauai Realty,” Clinton says. “Today we are one of the largest real estate firms on Kauai.”

Kauai Realty, now run by his son, Sherman, has 20 real estate agents, and Clinton’s family members serve as officers of the corporation. Clinton is still the president of the company.

Four shots a night

After operating his law firm, his real estate company, serving on numerous Kauai boards and commissions and dabbling in local and state politics for a short while (his campaign motto while running for Board of Supervisors: “Take a Hint — Win with Clint”), Clinton is now happily retired.

“I’m 93 years old, so I want to take it easy,” he says.

He enjoys spending time with his three children, six grandchildren and three great-grandchildren, all of whom live on Kauai. He and his wife, Fumiko, have resided at Regency at Puakea retirement community for just over a year.

Clinton still has the energy of a much younger man, a fact he attributes to his daily hour-long brisk walks from Regency, in loops through the town of Puhi.

And then there’s his whiskey.

“Four shots of whiskey or four shots of gin with my dinner every night. I’ve been doing that for many years,” he says. “I go to see my doctor regularly. I’ve told him about my drinking. He says, ‘At your age, continue to do the same.’ ”

As Clinton looks back on his life, he realizes the hardships that he and his family endured over the years paved the way for his life to unfold in the remarkable way it has.

“My mother was a very hard-working woman, and uneducated. Maybe for that very reason, she pushed all of her children to become educated,” he says. “I’m also thankful to my grandmother, who pushed my father to allow me to continue my education beyond ninth grade.

“A lot of my personal friends were killed in action during the war, and some very, very badly wounded,” he says. “I feel very, very fortunate and proud that I was able to serve my country, come home and serve Kauai.”

•••

Pamela Varma Brown is the author of “Kauai Stories” and “Kauai Stories 2.”