A vision fulfilled

When Ikito “Ike” Muraoka was a freshman at Kauai High School in 1936, he never could have guessed that as the result of a hunting accident, he would be given a glimpse into his future.

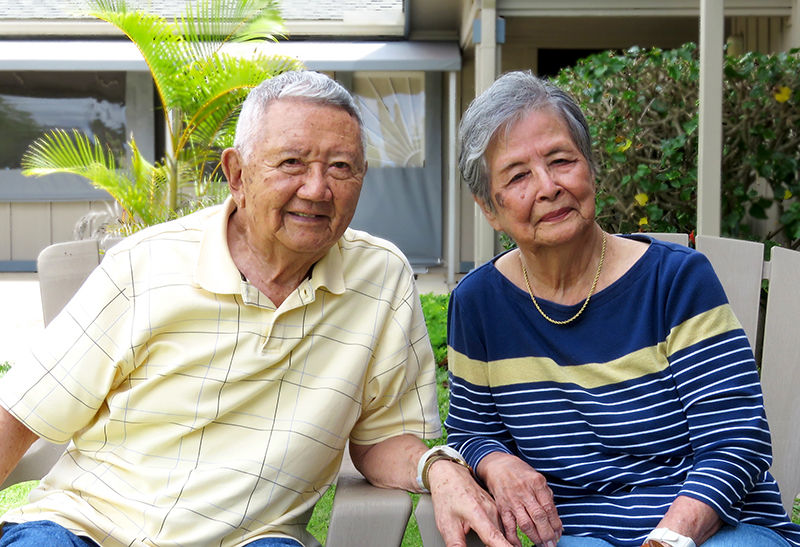

Looking much younger than his 93 years, with a calm demeanor and a rich baritone voice, Ike recalls that fateful morning clearly.

He and one of his brothers drove from their home in Koloa on Kauai’s South Shore to Mahaulepu Valley to hunt pheasants.

While Ike’s brother was standing on a knoll a short distance away, their dog flushed a pheasant out of the brush. The bird flew up and fluttered in the air between the two boys.

“I raised my shotgun and that’s the last I knew — because I was shot,” Ike says.

The bird had blocked his brother’s view of him. Pellets peppered the left side of Ike’s body, from his abdomen down though his left leg, plus a few in his right leg, and he was bleeding profusely.

His brother carried him from the valley to their car, which was parked about half a mile away, then drove him to Koloa Hospital, a sugar plantation hospital.

“While I was in a semi-conscious state, I had this incredible vision that I went off to war, was wounded, came back, got married and fathered two daughters,” he says.

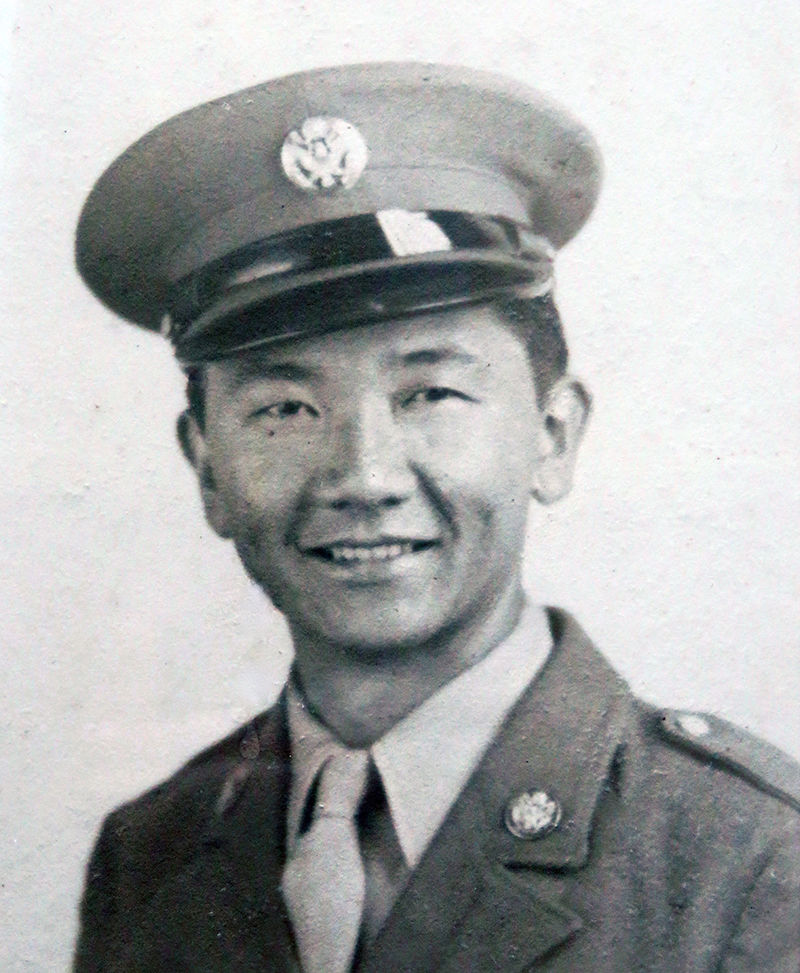

From soldier to medic

Five years later, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, drawing the United States and Hawaii into World War II. Like thousands of Nisei (first generation of Japanese born in America), Ike volunteered for the United States Army. The Army accepted him, even though most of the pellets from the hunting accident were still lodged in his body.

“They didn’t examine me too well,” he says, understating the military’s desperation for more bodies — and the Nisei’s determination to prove their loyalty to the country of their birth.

“What was hurtful was that the youngsters that I attended grammar school and high school with, they turned against us Japanese. We were suspected and treated as enemies,” he says. “We just wanted to prove that we were Americans. Our hearts were American.”

Ike became a member of the all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team that was soon combined with members of the 100th Infantry Battalion, comprised of former members of the Hawaii National Guard. Together they became known as the 100th/442nd. One of Ike’s older brothers served in the 100th.

The 15,000 soldiers of the 100th/442nd were sent to some of the bloodiest battles of the war, fought valiantly, and suffered tremendous loss of life. With their “Go For Broke” motto, the 100th/442nd became the most highly decorated units in U.S. military history, earning more than 18,000 individual decorations for bravery, including two Presidential Unit Citations.

In 1944, 200 members of the 442nd were shipped from the U.S. to Naples, Italy.

Ike was one of six men in that group who were placed in an impossible situation: After being trained to kill as combat soldiers, they were ordered to become combat medics.

“When we got shipped overseas, that’s when they told us. We had no choice,” he says, ruefully. “How do you train somebody overnight to do something as complex as being a medic? We were given about one week of training.

“You know what sticks in my mind? That I lost a dear friend during the war because I did not know enough medicine.”

Later that year, in Civitavecchia, Italy, near Rome, Ike was wounded as artillery shells began falling while his unit advanced on a hill. He was in a hospital for nearly one month, “then they sent me back to the unit again,” he says.

The entire regiment was sent to fight in southern France, where the men were ordered to save the “Lost Battalion,” a group of 211 Texas soldiers who had been stranded for days on a ridge in France, surrounded by German soldiers. The 100th/442nd successfully broke through the German line, but in five days of fighting, lost 800 men in the rescue.

For his wartime service, Ike earned a Purple Heart, a Bronze Star and, in 2011, the Congressional Gold Medal, awarded 66 years after WWII ended to all members of the 100th/442nd and the Military Intelligence Service.

“I never regretted my decision to volunteer for the war, but I was devastated when I lost my close friends,” he says. “I was very fortunate that I came back alive, but thousands of my comrades sacrificed their lives for this country.”

The first segment of his hunting accident vision was completed.

Meeting Nancy

Once he returned home to Kauai, Ike suffered from bouts of “shell shock,” now referred to as Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome, from his wartime experiences.

But he soon found a very pleasant diversion: a lovely young Japanese woman named Nancy, who was living at home with her father and siblings. (Nancy’s mother died when she was only 2 years old.)

“He pretended he was coming to see my brother, who had also recently come home from the war, but I think he was coming to see me,” says Nancy, now 88 years old, and radiating kindness.

Sixty-nine years later, Ike tries to play it cool with a noncommittal smile, but his dimples give him away.

“I really didn’t think much about his visits at first,” Nancy says. “But when he started to come and see me where I was working, I suspected that something was on his mind. I think when the men came back from the war, they were all looking for somebody they could marry.”

Soon Ike, along with some friends who were also veterans, began attending Honolulu Business College on Oahu, and Ike and Nancy continued their romance across the 90 miles of ocean between the islands.

Then in 1946, Ike made a very important phone call: “I proposed to her from Honolulu by phone,” he says.

“I said ‘yes’ on the phone but I didn’t tell anybody. He was coming by boat to see my father, bring a fish and ask for my hand,” Nancy says. “It’s the old-fashioned style, the way the Japanese think.”

After Nancy’s father gave his blessings, the couple returned to Honolulu together so Ike could resume his college career, and so they could get married on Oahu.

Ike had accomplished the second portion of his life vision that he received on the day of the hunting accident.

Longing for Kauai

After college, Ike worked as the assistant paymaster for Clark-Halawa Rock Company, then later worked his way up to chief clerk at Young Bros.

The couple’s two daughters were born in Honolulu, completing the third and final portion of the vision he had after the hunting accident.

But Ike found himself longing for Kauai.

“One day, without telling Nancy, I quit my job,” he says.

“I had the refrigerator door open when he told me,” she says. “I just stood there holding the door, with my mouth wide open.”

Though they had both grown up on Kauai, she the ninth of 10 children and he also one of 10, Nancy wasn’t overjoyed to return to a place “where the streets all rolled up at 5 p.m.”

But relocate they did, with Nancy eventually beginning a 22-year career at the Waiohai Hotel, which was then owned by Grace and Lyle Guslander, esteemed hoteliers who also owned the Coco Palms Hotel.

Ike, meanwhile, applied for an opening on the Kauai Police Department, where he began as a foot patrolman. “I worked myself up to be a court officer, a liaison between the police department and the prosecutor’s office,” he says. “I served a total of 16 years on the force.”

One of the court judges that Ike worked with was Norito Kawakami, a member of the Kauai family that had launched a grocery store chain, Big Save Markets (now owned by Times Supermarkets). Judge Kawakami invited Ike to join his family’s business.

Working in private industry was a big change for Ike. While the grocery store chain was growing, he put in 12- to 16-hour days, worked weekends and some holidays. During his longest days, Nancy drove from Koloa to Eleele to bring him dinner.

As he helped the company grow, Ike worked his way up to vice president of finance, and served on the board of directors before retiring.

But it was being appointed as the first former police officer to serve on the Kauai County Police Commission that is one of Ike’s proudest achievements. He served on the commission for eight years, two of those as chairman.

“It was rewarding work in the sense that I was able to contribute from my 16 years’ experience with the police department,” he says.

Blessings

Now, when Ike and Nancy look back on their long lives, the word they both use to describe their experiences is “blessed.”

“I am blessed to be alive, when so many of my buddies died in the war,” Ike says. “I’m blessed for having Nancy and our children, grandchildren and one great-grandchild.”

Though the couple recently moved from their home of 50 years in Koloa to the retirement living community Regency at Pua Kea in Lihue — a big adjustment for both of them — Nancy says they are extremely grateful for the “loving and caring staff” at Regency.

Ike says his secret to living so long is that, “Nancy keeps me going.” As does his gratitude for his entire life.

“I feel blessed that I have been so fortunate that I’m here talking to you.”

•••

Pamela Varma Brown is the publisher of “Kauai Stories,” “Kauai Stories 2,” and “Kauai In My Heart.” Visit www.writepath.net