Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of stories by The Garden Island marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Japan on Aug. 15, 1945, and the end of World War II. J.Q. Smith was serving in

Editor’s note: This is the third in a series of stories by The Garden Island marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Japan on Aug. 15, 1945, and the end of World War II.

J.Q. Smith was serving in the Pacific Theater when he heard the news about the atomic bomb being dropped on Japan, but he didn’t understand the scale of what had happened.

“It was not really significant because there were so many bombs and battles and things, that we didn’t understand it. We didn’t have the information,” the retired Marine recalled 70 years later. “We heard it was enormous and they would probably surrender, and we wouldn’t have to go in. We were scheduled to go into Japan and land in Japan if they hadn’t dropped the Nagasaki and Hiroshima bombs.”

As it turned out, Smith ended up going to Japan anyway, but much sooner than expected, and on a much different mission. His transport plane was assigned to go to Japan to drop off news crews at an airfield outside the destroyed cities just a few days after the bombs fell.

“What I remember seeing is just flat, one building, a post sticking up here, a part of a building sticking up there, we didn’t see any people,” the Kapaa man said. “It was devastated. We didn’t realize how devastated — we didn’t know the number of people killed or damages done. We were so happy they surrendered, those were the things that were generating in our mind, we were going to go home.”

Before going home, Smith spent nine months in China on a mission to remove the Japanese occupation forces who were put on a boat and sent back home for repatriation.

“It’s amazing that the Japanese — so small a little country — could occupy China,” Smith said. “But it was all out of fear, people would be scared to death. They controlled by fear.”

Despite being injured when a Japanese plane dropped a bomb on his airfield earlier in the war, Smith doesn’t have any anger toward his former enemy.

“You notice I don’t say Japs — I say Japanese. The Japanese people are wonderful people, they were fighting a war just like we were, and they were told to kill me before I killed them, and that was all there was to it.

“We all had the same goal — to get home alive.”

Once he got home, Smith signed up again. He later served in Korea, ferrying mail and supplies back and forth from Japan, and then in Norway during the Cold War on top of secret missions that included picking up U-2 pilot Francis Gary Powers about once-a-month after his spy flights over the USSR.

Smith made 1st Sgt., and served in the infantry in Vietnam, where he was injured while defending Hill 22 on Oct. 30, 1964. A bullet hit his rifle and ricocheted into his hand, driving his wedding ring into his finger.

“We were on top of a hill, and the enemy was all around us. It was really bad. I mean they came from all directions, every direction. There was only a few of us,” Smith said. “It’s still just like it’s yesterday. I can’t talk about it hardly. It’s very hurtful. I saw my buddies get killed. I saw my buddies get wounded. I saw myself — I didn’t care. All I wanted to do was help them. I carried with one hand stretchers to the airplane and wouldn’t get on the airplane until ordered to do so.”

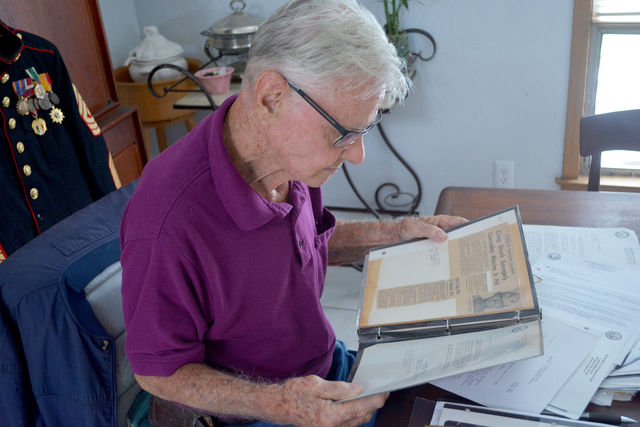

Smith, who was 17 when he joined the Marines in 1943, got emotional when reading a letter from his commanding officer, thanking him for his bravery in action that day.

By any definition, he is a hero. He fought in three wars, and was injured in two of them. Decades later, the wars are history for much of the world, but he still remembers.

“It hurts so bad sometimes, you don’t eat, you don’t sleep, you don’t do anything. You just grieve. And it’s like yesterday. It’s not like a long time ago. And things hit you.”

But J.Q. is a survivor — a skill that was taught to him by his brother H.E. “High Explosive” Smith.

“My brother said you’re not any good to anybody dead, so you’re only good if you can survive.”

“The idea of war is to survive. You are no good to anybody unless you survive,” he said. “Survive, survive, survive. And this is what I’ve used all my life.”