Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of stories by The Garden Island marking the 70th anniversary of the surrender of Japan on Aug. 15, 1945, and the end of World War II.

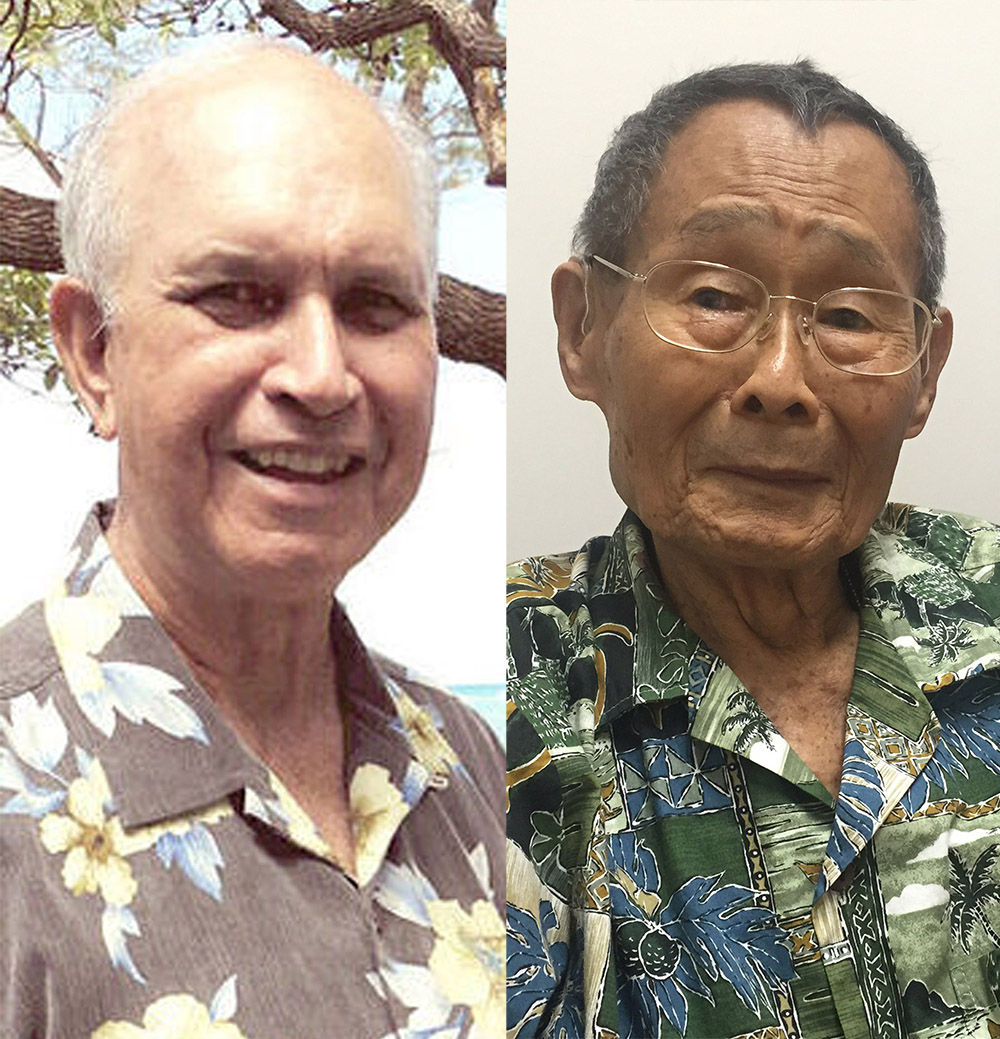

Bill Fernandez was 10 going on 11 and living on Kauai when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941.

The Kapaa man remembers in detail quite a bit from the war: anger toward Japanese residents, plantation life and culture, fear of invasion, martial law.

However, one thing he vividly recalls is the people of Hawaii uniting — regardless of skin color and culture.

“There was a lot more cooperation between people. People began to realize that we had to pull together to get through this,” he said. “I think the war and the fear caused people to pull together. What you found with the war, it really started new friendships that developed because of the rationing, the fear of invasion.”

It wasn’t smooth in the beginning, recalled Fernandez, who went on to graduate from Stanford University, become an attorney and judge and served as mayor in Sunnyvale, California.

“Suddenly you had a new system of regulation that was imposed by the military. You had rationing blackouts, curfews, etc,” he said. “There was an initial animosity toward the Japanese people that were here.”

However, there were no acts of hostility by the Japanese population, he said.

“In fact, from what I could see, it was a desire to show loyalty to the country and overcome the stigma on the attack of Pearl Harbor,” he said.

One Japanese American who proved loyal was Kazuma “Monty” Nishiie, a veteran of the 100th Infantry Battalion, a group comprised almost entirely of Nisei, the first generation of children born in America from Japanese parents.

Prior to war, Nishiie was part of the National Guard on Kauai.

“They decided to corral all the Japanese Americans and send us away,” he said.

A contingent of 1,400 soldiers, who were mostly Japanese Americans, ended up in Wisconsin for training.

“We caught hell because Hawaii guys don’t know the cold of Wisconsin,” he said.

Monty said the U.S. had its eye on the battalion of Japanese Americans.

“When war started, there was bad feelings with the Japanese,” he said. “We had our training in Wisconsin and all the time people in America was watching that.”

Back home in Hawaii, Fernandez said the people were under martial law.

“Because you had curfew at 6 o’clock, for the first few months of the war, you were confined to the house,” he said. “You had local wardens that were there to police your areas. The military courts were strict if you were caught. Up until March, we were homebound.”

Fernadez said after the Battle of Midway, the curfew rules relaxed and different families began to fraternize.

“It was something you haven’t had before: groups getting together at night to socialize,” he said. “People began to laugh. Despite the seriousness of the situation, we found ways to make life entertaining.”

On the other side of the world, in 1943, Monty Nishiie and the 100th Infantry Battalion set sail from Africa to Italy.

Monty and the 100th received a moral boost when their colonel vouched for the group of Japanese Americans soldiers.

“The general from the 34th Battalion asked colonel , ‘Can you depend on them?’ ‘Absolutely,’ he told the general,” Nishiie said. “The general said, ‘I will take anyone under my command; anyone who wants to fight. To me that was a second moral booster. That’s how we ended up in the 34th division.”

Nishiie, part of a mortar platoon, was wounded near Monte Cassino, Italy, the same year.

“I don’t know exactly, but a mortar or artillery shell burst,” he said. “My arm and legs were hurt.”

Nishiie was lucky, but others weren’t.

“Two kids were direct hit from mortar and they couldn’t identify them,” he said. “The other one, our lieutenant, had a direct hit too and died.”

Nishiie spent the remainder of the war healing in a Naples Hospital.

“When I became well, the staff of the hospital put me in charge of the laundry department,” he said. “I stayed there until the war ended in Europe in 1945.”

Before war ended, martial law was lifted in Hawaii.

“We young people weren’t used to freedom. We weren’t used to due process,” Fernandez said. “We lived under a plantation mantra: ‘These are our regulations. You go to bed at 8:30. You don’t fraternize. Lights out.’”

Fernandez credits people from the Mainland for starting the movement.

“For the haole who has been accustomed to due process, for people on the mainland who were accustomed to due process, this system of martial law was very upsetting,” he said. “I can’t say it was grassroots movement for change.”

Postwar mentality and a newfound knowledge from the war brought big changes to the islands, said Fernadez, who wrote a recently published memoir about his experiences, “Hawaii in War and Peace.”

“When you’re talking about peace, we had been plantation economy, we had been controlled by the sugar people,” he said. “With the end of war, you had union people from the Mainland say that your way of living was wrong.”

The Great Hawaii Sugar Strike in 1946 against the Big Five Hawaii corporations (Alexander & Baldwin, American Factors, Castle & Cooke, C. Brewer, & Theo. Davies) brought better working conditions to the people, Fernandez said.

“The post-war era was real awakening for the people of color. The people of color wanted better working conditions,” he said. “The knowledge that war brought expanded into freeing people from the imprisonment of plantation culture. Postwar was a development of self-worth among the different races that were here.”

For Monty, he spent the remainder of his life hunting, fishing, working and with his family.

The recipient of a Purple Heart and the Congressional Gold Medal seldom speaks about the war.

But at 100, he’s as loyal as ever.

“We had to show America that we were Americans,” he said. “We had a big responsibility.”