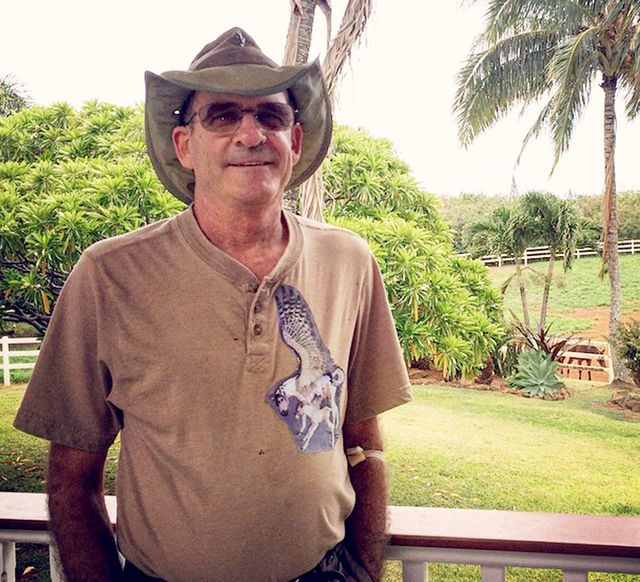

Physically speaking, Scott Sims feels fine. He’s got a sore rib from a horse he treated that bonked him around a bit. And he’s tired from the last few nights during which he’s been sleepless. But he’s still able-bodied enough

Physically speaking, Scott Sims feels fine.

He’s got a sore rib from a horse he treated that bonked him around a bit. And he’s tired from the last few nights during which he’s been sleepless. But he’s still able-bodied enough to pin down a pot-bellied pig in order to sedate him like he did on an episode of Nat Geo Wild’s “Aloha Vet.”

Emotionally, Sims feels less in control.

He’s feeling stunned and loved and weepy and, perhaps most of all, lucky.

Lucky to have received a medical diagnosis Monday that he would like to erase, and yet simultaneously views as a strange and special gift.

On Tuesday, Sims changed the voicemail greeting on the cell phone he’s now famous for answering day or night, whenever there’s an animal in need.

“I have been diagnosed with what may be a fatal cancer.” His voice is slow and matter-of-fact. “As such, I will do my best to take care of you and your pets for as long as I can, but please forgive me if I’m unable to get to you.”

Scott Sims is the nation’s barefoot Aloha Vet, the unconventional animal doctor whose adventures with cattle and goats and horses and hens garnered a million viewers in the premiere season of his very own reality TV show. On Kauai, he is the island’s only veterinarian to animals both large and small, just a phone call away from performing mouth-to-beak CPR on a wild parrot.

Now, after getting word that there’s a large tumor on his bladder and several more masses on his liver, Sims will spend the days that he said may very well be his last advocating for something new: quality over quantity of life. Not only for animals, but for people, too.

The biopsy results haven’t come back yet. Decisions about what treatments he’ll undergo haven’t been made.

What Sims does know is that he’ll fight as long as there’s fight left in him. He’ll seek whatever treatments will give him a good quality of life, and pass on those that will prolong his days, but not his days well spent.

“I have had a fantastic life,” Sims, who is 59, told The Garden Island Thursday from his perch beside his African grey parrot’s cage in the living room of his Kilauea home. “I have had great friends all over the country. I have a career that I care about that I have been reasonably successful at. My gosh, I had a national TV show.

“And now I get a bonus.”

He paused, sealing his eyes for a long blink. Then he continued.

“I get — in exchange for a few years, maybe — I get to know approximately when I’m going to die. And I get some warning. I get to tell the people that I care about that I care about them and they get to tell me what they want, good or bad.

“A lot of people don’t get that.”

Sims paused for another long blink. This time, his eyes were brimming.

Five days before a doctor told Sims he likely has bladder cancer, the same disease that led to Sims’ father’s death, Sims said he got word from the folks at Nat Geo Wild that the network would like to air a second season of “Aloha Vet.”

Sims is compelled now more than ever to film a new season that focuses not only on his animal rescue attempts, but on his own quest to live a full life when death seems to be looming around the next corner.

“We shut old folks away in homes because we don’t want to see death and what it does to us,” Sims said. “But it’s a part of life and we shouldn’t bury our heads in the sand from it. We all die, every last one of us is going to die. To ignore it and hide from it because we don’t particularly relish it, I think that’s a mistake.

“I have an opportunity to change the way people think about death. And if I have to lose a little privacy along the way, I am OK with that.”

There’s something else Sims wants to accomplish. Using his newfound celebrity — “That ‘Aloha Vet’ thing” — Sims wants to establish and raise money for a new nonprofit, pay-what-you-can animal hospital on Kauai.

Outside the hospital, Sims imagines a jar with a sign that reads, “If you can put something in, great. If you can’t, thanks and come again.”

“If I don’t have an end to my story yet, I’ll run it,” Sims said. “But if this is the end of me, then it can go on without me. That would be some sort of legacy.”

•••

Brittany Lyte, enviromental reporter, can be reached at 245-0441.