KILAUEA — The presentation about federally proposed changes to the humpback whale sanctuary could hardly be heard over the profanity-laced protest of Mitchell Alapa. The Kilauea resident declined requests to leave the public hearing at Kilauea School Monday, saying “shut

KILAUEA — The presentation about federally proposed changes to the humpback whale sanctuary could hardly be heard over the profanity-laced protest of Mitchell Alapa.

The Kilauea resident declined requests to leave the public hearing at Kilauea School Monday, saying “shut up” to anyone who asked him to be quiet. Instead, he hollered from the back of the room about his disdain for the non-native Hawaiian people and agencies seeking to manage a greater sweep of the island chain’s waters.

Hours later he apologized — “I’m sorry about the way I sounded earlier” — while testifying in a more composed manner about what he sees as the slow takeover of Hawaiian resources by outsiders.

Not everyone in the crowd of 150 residents gathered at the meeting agreed with Alapa’s disruptive methods. But his temper was indicative of a widespread anger in the testimony of captains, fishermen, surfers and local business owners, who made it clear they will do whatever it takes to fend off what they view as the increasing oversight of state waters by a federal government they don’t trust.

“I know that tensions are high, and that’s why we’re here,” said Sanctuary Superintendent Malia Chow, who led the first of three public hearings on Kauai this week.

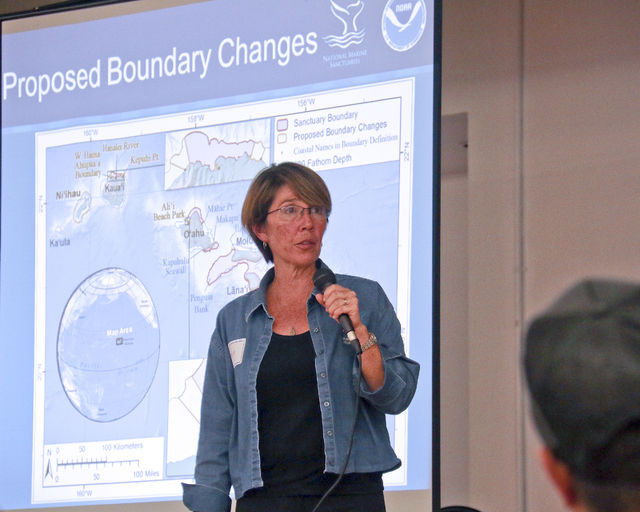

At issue is a new management plan for the Hawaiian Islands Humpback Whale National Marine Sanctuary. The crux of the proposal is a sanctuary boundary expansion to include 235 square miles of new state and federal waters around Kauai, Niihau and Oahu, bringing the total sanctuary area to 1,601 square miles. The plan would also extend the sanctuary’s focus from just whales to other marine species and generate new opportunities to work closely with community groups on priority resource protection issues.

Co-managed by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the state of Hawaii, the sanctuary aims to protect humpback whales and their habitat while educating the public on the relationship between humpbacks and Hawaii’s marine environment. It is one of the most important humpback habitats in the world.

All proposed changes to the current sanctuary border are the result of requests made by community members, Chow said. For example, the Robinson family that owns Niihau requested that the waters around the perimeter of the private island be included in the sanctuary. A proposal to restore the reef at Pilaa in Kilauea using a crossroads of modern science and traditional Hawaiian management practices was born from a request by the University of Hawaii’s Center for Hawaiian Studies.

All told, the plan calls for a 16 percent expansion of sanctuary waters around Kauai, with add-ons in Haena, Hanalei and Kilauea.

In Haena, the western boundary of the sanctuary would be extended to include the full Haena Community-Based Subsistence Fishing Area. In Hanalei, the sanctuary border would broaden to include portions of the Hanalei River. The plan for the Kilauea coast is to create a designated area to pilot traditional Hawaiian marine management approaches alongside modern science-informed techniques to restore the degraded coral reef.

Then there’s the three nautical miles around Niihau that’s drawing fire from locals who fish there.

Chow was quick to shoot down one of the fishermen’s biggest fears: “We are not closing off any areas of the sanctuary and we are not regulating fishing,” she said. “You can continue to fish at Niihau. You must follow all state regulations, but there will be no regulations under the sanctuary.”

This fact, however, was met with widespread disbelief, some of which is rooted in a deep distrust of the federal government that began long ago with Hawaii’s contentious road to statehood.

“You say there’s going to be no fishing regulation, but is that forever — yes or no?” said Haleakala Anakalea, 33, of Hanalei. “I think it’s not. I think you say there’s no fishing (regulations), but five years from now it could change. And that’s how everything starts. Overdevelopment, all this stuff, it starts with little steps and it gets bigger and bigger and bigger and all of a sudden you lose all the things that we used to have. And that’s why a lot of people are upset. That’s why I’m upset, because I feel like it’s enough already.”

Dave Stewart, 59, of Hanalei called the proposed sanctuary expansion a prime example of overregulation, saying the island’s marine life already has sufficient protections.

“I just don’t want to see the entire North Shore of Kauai be run by a federal agency and (watch it) gain control of the entire area and its resources with little public involvement,” he said. “C’mon — Three two-hour meetings and then that’s our life for the rest our lives and our kid’s (lives)?”

He paused to regain his composure.

Speaking lower and slower, he continued: “After hundreds of years of managing our own resources, you guys want to come in and manage our resources for us. That’s sad.”

Not everyone spoke against the plan. Carl Imparato, 63, of Hanalei, said the islands could use the federal government’s vast resources to protect its waters and marine life.

“I do not fear federal presence, rather I welcome federal presence and all the resources and impartiality and protections that it brings,” he said.

Maka’ala Ka’aumoana, another sanctuary supporter and the executive director of the Hanalei Watershed Hui, said some proponents of the plan chose not to attend the meeting because they are reluctant to voice their opinion in such a contentious atmosphere.

Indeed, supporters of the plan were severely outnumbered.

“How many of you do not trust the federal government to manage our resources?” asked Scott Mijares, 54, of Kalihiwai.

A hand from nearly every person in the room shot to the sky — including Chow’s.

“I also don’t trust that big institutions like the federal government always get it right,” she said. “So the reason I stayed working for the federal government is because I believe that people need a voice to be able to navigate through all the bureaucracy. I live it everyday and I know that unless there are champions for the people working in the federal government, I hate to say it, but the federal government will screw it up.

“Tonight it an example of democracy at its best. It’s messy and it’s uncomfortable and people get passionate, but at the end of the day I just hope we come up with something that people understand.”