At 93 years old, Castora Guillermo Suero remembers her days growing up in sugar plantation camps and working for a pineapple cannery as if they took place yesterday.

“I worked for Dole cannery in Honolulu when I was 16 years old, night shift, 35 cents an hour, from 2 o’clock in the afternoon to 10 p.m., cutting, trimming pineapple skins,” the Lihue resident says, her eyes re-tracing the path of pineapples rolling endlessly down a chute and landing in front of her.

“The pineapples would keep coming. You gotta be fast!”

Castora gave the wages she earned to her mother to supplement their family’s income. Her mother, Guadalupe, also raised ducks and chickens and sold their eggs to help make ends meet.

“At that time, my father earned $1 a day! Not enough but everything was very cheap,” she says, recalling that a 100-pound bag of rice cost less than $5.

Her father returned $1 to her per month to pay for her lunches, supplied by the cannery for five cents per day. “It came on aluminum plates, maybe stew, sandwich, rice and milk in a small little glass bottle,” she says, her fingers curling around the bottle that she can still see in her mind’s eye.

What about eating pineapples if she got hungry while working at the cannery? “The small ones, they just like sugar,” she says with a broad smile.

Cannery employees were of “all makes,” Castora says. “When you’re of age, either you go to work at the plantation or pick up pineapple in the field or work in the cannery. In those days, no such thing as hotels except in Waikiki, and that was too far from our house.”

New life in Hawaii

Castora’s family immigrated to Hawaii from the Philippines in 1923, when Castora was only 1 year old. Guadalupe was required to tell authorities that her baby girl was 2 years old in order for her to be allowed to come with them on their voyage to their new life in Hawaii.

Castora’s father, Eulagio, had been recruited by the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association, along with other men from the northern region of Luzon in the Philippines. The family made the long journey from the Philippines to Hawaii by ship, traveling in steerage, as was customary for most prospective sugar plantation employees, who could afford only third class.

For years Castora has carried in her wallet a photograph of her with her mother taken shortly after they arrived in Hawaii, the young woman’s hand resting on her daughter’s knee, her face looking much like Castora’s did when she was a young girl.

When the family arrived in Hawaii, Eulagio was chosen by Oahu Sugar Company in Waipahu on Oahu to be a “cut cane” man. He worked with a crew of about a dozen other Filipino men who harvested the tall stalks of sugar cane using a machete after “burn days,” the days the plantation purposely set fire to acres of sugar cane to burn off unneeded green leaves.

“On burn days, when all the men come home from work, they covered in soot,” Castora recalls, in her still-thick Filipino accent. “Only the eyes and the teeth you can see.”

Her mother worked as a laundress, collecting the dirty laundry of two or three men once a week, washing all their clothes outdoors in a galvanized metal bucket, adding lye to help remove the soot.

“My mother used to get the day-old rice and she would cook it some more, add water and put it in an empty bag and massage it to make starch. That thing is very stiff!” she says. Then her mother would dry, iron and fold the laundry, all for $2.50 per month.

Castora and her family lived in a sugar plantation camp in Waipahu, surrounded by other plantation families of a variety of cultures.

“Was good fun!” she says, but as a child, differences were apparent.

“Those days, oh, you gotta walk to elementary school,” she says. “All the Japanese, Chinese, Portuguese and Filipino children all walk, but the Americans come in car.”

Castora remembers the simple single-walled, wooden frame housing provided by the plantation so clearly that she draws a diagram on the table with her finger, indicating where each of the two rooms was located. She still sees in her mind exactly how many steps led from the front porch to the outdoor kitchen, which was located next to the community restroom.

Bathing was communal in those days, too, with hot water heated by a fire beneath a huge wooden tub. People sat in smaller tubs nearby and scooped hot water onto themselves from the larger tub.

“You gotta take a bath before the men pau hana (finished work),” and used up all the hot water, Castora says. “No shower. No such thing as that in those days.”

When the family was eventually upgraded to a newer plantation house, in addition to three bedrooms, they now had a shower.

“Oh, was good!” Castora says. But that shower was cold water only. “Amazing what we went through,” she says.

‘Oh, it was good fun’

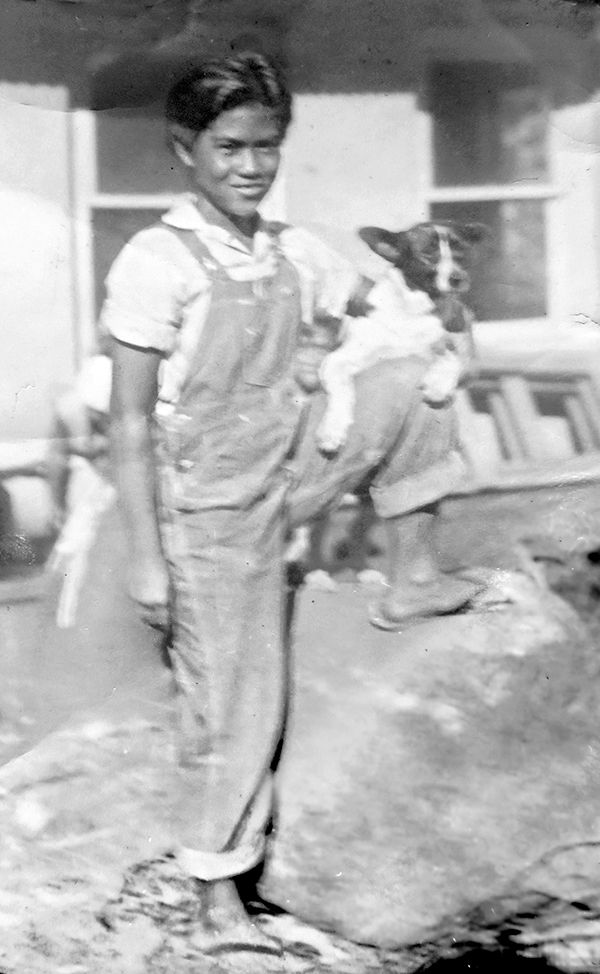

Petite as she is now, it’s hard to imagine Castora as a tomboy, but in high school that’s what she was, wearing overalls, playing volleyball and also playing catcher on a baseball team.

“I used to get good fun. I would throw the ball like a young man. I was a good hitter, too,” she says. “I tell my children and grandchildren I used to be catcher. They don’t believe me so I show them the picture.”

She recalls how catchers’ uniform pants in those days were balloon-like.

“The ball got stuck in the balloon pants and they couldn’t find it,” she recalls, laughing. “Oh, it was good fun watching that!”

But it was playing tennis that turned out to be the most fortuitous sport for Castora.

Wearing uniforms of golden shirts and short pants supplied by Oahu Sugar, Castora and girlfriends played tennis without a coach, simply having fun.

Then one day a coach appeared, one Catalino Suero. He and Castora hit it off — and soon got married. Though Catalino has passed on, Castora still refers to him lovingly as “My Catalino.”

Castora and Catalino moved from Oahu to Kauai in the 1950s when Catalino, who worked for the Hawaii Sugar Planters Association as a supervisor in sugar technologies, was assigned to Lihue.

When they first arrived on Kauai, they stayed at the Kuboyama Hotel (now the Nawiliwili Tavern), and later rented a home from Mamoru Kaneshiro (then-owner of Kaneshiro Hog Farms) in Kalaheo for $35 per month.

‘Was good, very good!’

Today, Castora is grateful for her five children, 14 grandchildren and numerous great-grandchildren, her vivid memory and her excellent health.

She has recovered well from an accident she had in March 2008 when, leaving church, she walked outside, “I never looked up or down. A truck banged me,” she says. She gets around in a wheelchair and though her children would prefer she stay indoors, she still has that spunky tomboy in her.

“Sometimes, I go out in the yard. I never tell my children. The grass is lumpy, I fall down. I drag my body up and push myself into one small chair,” she says. “Then I look around, lucky thing nobody’s watching.”

She takes stock of all the progress she’s seen in her 93 years, especially on Kauai. “When we first came to Kauai, 5:30 in the afternoon, everything is closed up,” she says. “The only place that was open used to be Club Jetty (a now-closed Nawiliwili night club).

“Coming from Kalaheo in the afternoon, you hardly met any cars, only one or two cars coming,” she says. “Now, chain of cars. Amazing!”

And she looks back with fondness on sugar plantation days.

“It was the lifestyle for all the people,” she says. “Was good, very good!”

•••

Pamela Varma Brown is the publisher of “Kauai Stories” and the forthcoming “Kauai Stories 2.”