Kauai’s Bill Peterson was looking forward to the movie, “Unbroken,” which depicts the life of Louie Zamperini, Olympic runner and World War II prisoner of war. It wasn’t because he had read the book by Laura Hillenbrand, but because his

Kauai’s Bill Peterson was looking forward to the movie, “Unbroken,” which depicts the life of Louie Zamperini, Olympic runner and World War II prisoner of war.

It wasn’t because he had read the book by Laura Hillenbrand, but because his father, Charles “Pete” Peter-son, spent more than three years in Japanese POW camps.

He lived through starvation and disease and beatings. He survived what Zamperini survived.

“I think if my father were still alive to see the film, he would say what he did of the book: ‘Over-dramatic, but true,’” said Bill, who saw the movie at Kukui Grove Cinemas.

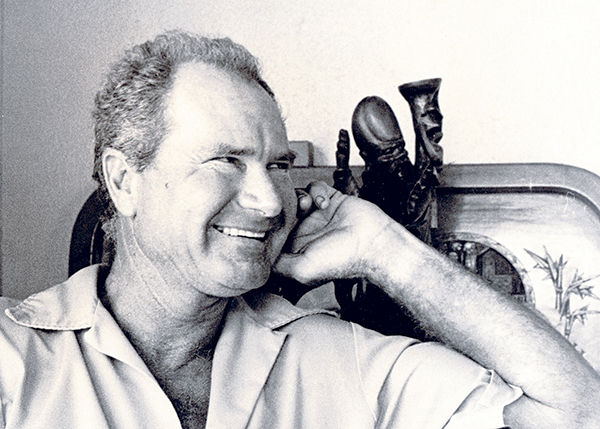

Pete Peterson died July 18, 2012, at the age of 91. His influence lives on. To this day, when faced with an opportunity or challenge, Bill thinks about how his father would react. What would he do?

”I’m honored to have been his son,” said Bill, who today lives with wife, Sea, in the Kapaa home that was once his father’s.

Bill, a meticulous record keeper, has his father’s war medals and honors carefully protected in a glass case, including a Bronze Star. There are black-and-white photos of his father as a young man in his military uniform. There are pages of information about Pete Peterson. There are newspaper clippings, a letter from the War Department, and notices to Pete’s parents via Western Union about his return home following the war.

Bill displays a copy of the book, “Death March: The Survivors of Bataan,” by Donald Knox because it includes a photo of his father when he was a POW. He has a DVD of the 2001 movie, “To End All Wars,” a true story about four Allied POWs in World War II, because some of it was filmed on Kauai and Pete was brought in a consultant. There’s a photo album, with more pictures of Pete, his beloved wife Dottie, the places they lived and the lives they touched.

Bill has typed out his father’s story of his World War II experiences, his life after the war, his love for his wife of 44 years, his willingness to try anything. He was a man who would tackle anything with a friendly smile — but who was also a fierce warrior when necessary.

It is a stirring tribute.

Bill leaves no doubt how he feels about his father.

“He was always my role model and my hero,” he said.

World War II

Charles A. “Pete” Peterson Jr. volunteered for the Army after leaving Point Loma High School in California. In the days before Pearl Harbor, his father, Charles A. Peterson Sr., advised him to “avoid the war in Europe” and volunteer to serve in the Philippines. As a result, he was a corporal, working in the headquarters unit Corregidor on Dec. 7, 1941, and shortly after, the Philippine Islands.

As the invading Japanese forced the American and Filipino troops to retreat, Pete was reassigned to operate a weather station on Bataan. After the Japanese blew that up, he operated as a forward artillery observer.

Eventually, the Japan forced the surrender of the “Defenders of Bataan.” Pete and another enlisted man escaped by swimming across the two-mile channel to Corregidor while hanging on to a log.

There, he took on many tasks — repairing communication lines, destroying U.S. currency so the Japanese would not capture it, volunteering to drive an ambulance up to the topside gun emplacements to rescue wounded.

The ambulance fell under fire on its return and crashed off a destroyed road. Pete only had time to bail out of the doorless ambulance before it went off the hillside. The crash killed the nurse and wounded Pete in the back. Pete was awarded a Bronze Star. He refused to accept a Purple Heart.

During the “Battle of Corregidor,” Pete operated a machine gun nest defending the beach at North Point, stopping Japanese forces from landing. He and his ammunition handler literally melted the barrel of the 50-caliber machine gun they were using, had to fall back to a water-cooled 40-caliber machine gun, and continued to defend the beach. It was in vain.

Surrender

Pete, along with the other 11,000 defenders of Corregidor, was taken prisoner and transported to Bataan. There, the prisoners were marched long distance under horrendous conditions to various POW camps in the Philippines.

Pete’s parents received a letter from the War Department on May 21, 1942, that their son was considered “missing in action,” from the date of the surrender of Corregidor on May 7.

“They didn’t find out he was alive until about two years later,” Bill said.

For the next three years, three months and 28 days, until after the Japanese surrendered in September 1945, Pete survived beatings, malaria, dysentery, starvation, mock executions, frostbite and forced labor. The death rate of American POWs was more than 40 percent.

Bill wrote that his father survived “because of luck, youthful toughness, his spirit and his sense of humor. He survived the marches, the camps, even the ‘Hell Ships’ transporting POWs from the Philippines to Japan. He survived having one Hell Ship he was on sunk by a U.S. submarine and another break down during a storm. He survived the forced labor camps in Japan, even the firebombing of the city of Toyama.”

In 1945, Japanese troops suddenly abandoned the camp where Pete was imprisoned. Several days later, an American plane buzzed the camp and landed in fields nearby. A short while later, a single U.S. sergeant came walking up the road into the camp carrying a light machine gun. He announced that the Japanese had surrendered.

The war was over.

In November 1950, under the War Claims Act of 1948, Pete was awarded a total of $1,216 for the time he had spent as a prisoner of Japan.

Home

Pete returned to California in October 1945. He spent time in a VA hospital until he borrowed a uniform and crawled out a window. His experiences had left their mark; he suffered periodic bouts of malaria and occasional nightmares.

Pete went on to work at the Firestone Tire factory, where he met Dorothy, who would become his wife. He and his brothers opened a service station in Los Angeles. He worked with Douglas Aircraft, took up boating and scuba diving, ran a mooring service and did underwater salvage work.

In 1983, Pete and Dottie retired and they moved to Kauai. They lived first in Hanalei, then eventually moved to their “Vagabond’s House” in Kapaa.

“They were pretty much inseparable,” Bill said, until Dottie died from cancer in 1989.

On Kauai, Pete made friends, spent time with his grandchildren, Kellie and Colin, fixed TVs and VCRs for neighbors, and always had a project of some sort in the works. In his late 80s, with an artificial hip, he still rode his bike on Ke Ala Hele Makale, where he loved to stop and chat with people.

In 2007, after Pete broke his other hip, Bill and Sea retired and moved to Kauai to help him.

Just after his 91st birthday, in 2012, he was diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer.

“He faced his death, as he faced everything else in his life, with courage, strength, concern for his family and an irrepressible sense of humor,” Bill wrote.

A son’s reflections

Bill read about many POWs who returned home from the war destroyed by their time in the prisoner camps. For some, depending on what they endured, it was too much to overcome. Pete, while living through his share of difficulties, fought through it.

“Attitude has a lot to do with all of it. Pete always had a good attitude,” Bill said. “He always downplayed his time as a POW. Never told us the real nasty stuff.”

Pete talked more about his war experiences in his later years. He told of sneaking fruit from a garden while living on one rice ball a day. He spoke of the starvation and disease that claimed many American lives. He spoke of hope. There was always hope.

“It was a nasty situation,” Bill said. “The guys were forced to do things they would never even consider, just to survive.”

Bill described his father as “extremely easygoing, very approachable,” but behind the friendly smile was a hard man who had survived what killed many. He could be strong and tough as needed — he was a man you wanted on your side.

“His hands were so tough, he’d brush barnacles off chains with his bare hands,” Bill said.

After the war, and after three years as a POW, he told his son that for the rest of his life, he feared nothing.

Like Zamperini, Charles “Pete” Peterson could not be broken.

“He said nothing could ever scare him again because he’d been through the worst that could possibly be thrown at him,” Pete said. “He didn’t really seem to be afraid of much of anything. He was just an amazing guy.”

•••

Bill Buley, editor-in-chief, can be reached at 245-0457 or bbuley@thegardenisland.com.