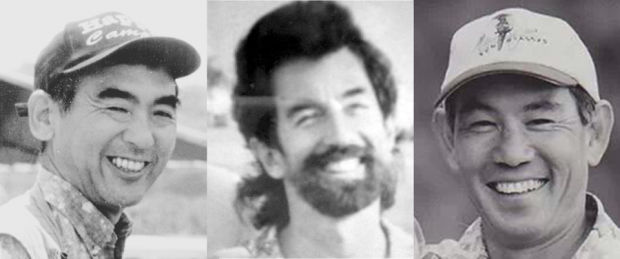

Our eyes, our ears, our voices

The three media icons gathered recently to talk story about what it’s been like to cover Kauai, decade after decade. They shared memories as well as a few anecdotes about each other.

Editor’s note: This is the second of two parts. The first was published Thursday in TGI.

The three media icons gathered recently to talk story about what it’s been like to cover Kauai, decade after decade. They shared memories as well as a few anecdotes about each other.

A DJ, a television host and a newspaper guy walk into an event. In some places, that might trigger a showdown. But on Kauai, where Ron Wiley, Dickie Chang and Dennis Fujimoto have been covering the same events for several decades, it’s a mutual admiration society — and that’s no joke.

“I don’t even remember when we all got together, but from the start, it seemed like we were all working together,” Fujimoto said. “There was nothing that said, ‘Oh, I’m the enemy.’ So that’s how it goes. And if people don’t put up the walls, there’s nothing to run into. And that’s how it is. And we’ve been running together ever since.”

The trio remember becoming aware of each other during the aftermath of Hurricane Iniki.

Wiley and Fujimoto were covering the devastating hurricane as newsmen, and Chang did his first Wala‘au show on the 1,100 people who lost their jobs when the storm devastated the Westin Kauai at Kalapaki (now the Kauai Marriott).

Wiley first remembers Fujimoto “when he was working for Kauai Times, with his camera and his vest.” That sparked a side discussion: how many vests has the Happy Camper gone through in all those years? Fujimoto shrugged, “I don’t know; don’t count.”

He admitted that the recent appearance of a newer, sturdier vest — “with more pockets!” — sparked outrage from folks who wanted him to donate the old one to the Kauai Museum, to be preserved as an artifact of island history. Fujimoto waved off such notions. But what happened to the old vest?

“It went in the landfill. It had holes in the holes,” he declared unapologetically.

But back to how they met.

“Out of respect: who didn’t know Dennis Fujimoto?” Chang asked.

But the Chang/Wiley relationship has a bit more back story.

“The interesting thing about it is, I knew of Ron Wiley, because we both came from Oahu, and he was a very successful radio guy with an incredibly popular radio station,” Chang recounted. “So as kids, we used to listen to Ron Wiley. So when I came here, then of course, it was Ron Wiley on the radio, and as an Oahu boy, born and raised, I was like, ‘Brah, we got Ron Wiley!’”

But the pair didn’t actually meet until Chang was running for office in 1992.

“It was him and Lee Cataluna, and they were (disc) jocks, and they were nicknaming all the candidates as cartoon characters, and I was Tweety Bird,” Chang related, directing a sour face at Wiley. “I didn’t come up with that!”

Wiley protested through his laughter. “That was Lee Cataluna! Who is a bona fide, genuine comedian — the real thing! But Dickie didn’t think it was all that funny.”

“So he wanted to straighten out what his name was,” Wiley picked up the story.

“So that’s how we met. Lee Cataluna was poking fun at his name, and I didn’t know the difference. And didn’t know what was going on. So that’s when Dickie called me, and I didn’t know who he was. And that’s when he gave me that phrase: ‘Ron, you’d go a lot farther on Kauai if you’d remember people’s names.’ And I’ve never forgotten that.”

It’s a bit of advice that never really took hold.

“Dickie is the king of knowing people’s names. Names, phone numbers, batting average,” Wiley explained. “I, on the other hand, am just the exact opposite.”

Wiley is so bad, he even promises cash or dinner to folks if he forgets their name.

“But faces! I remember where I met them, how I met them, what they were doing, and just about anything that is important, in my mind — except their name,” he said.

And he does have a knack for remembering voices, which comes in handy when callers try to cheat contests. As for that threat, back in ‘92, that he’d go far if he could remember names? Wiley is still laughing about that.

“Well Dickie, I’ve done it anyway!” he crowed.

Non-competitive competitors

“I never thought of us as competitors — never ever,” Chang said emphatically, as Wiley agreed: “Never did.”

“It was always about doing the right thing for the community,” Chang said.

“We’re in the same business,” Fujimoto said. “But it’s like looking at a basket with fruits: there’s apples and oranges.”

Perhaps it helps that the three of them cover stories from different angles.

“There’s a huge difference between print, video and radio. And they attract different senses,” Wiley explained.

Within the different formats, each has their own following, Chang pointed out.

“With Dennis, a picture tells a thousand words, Ron talks about it after, and Wala‘au gets it from the horse’s mouth.”

“There’s no jealousy,” he added.

“It’s a friendly rivalry.” Fujimoto agreed. “Because we’re all in this business together, and we have the same goals.”

“We all want to get the story right,” Wiley said. “And — maybe — snicker a little bit when somebody else doesn’t.”

“Often people will call me an entertainer,” Wiley continued. “But I am also a news person, and I am required to, by my own edict, to report on what people will be talking about. And I have a pretty good feel for what people will be talking about. As a radio personality, trying to do the feel-good stories that Dickie does … I’m also going to say when someone on the island gets arrested.”

There is, of course, a natural competition for advertising dollars. But nowadays, Wiley said, more businesses are realizing that they need to advertise in all formats, as well as social media and guerrilla marketing.

“They need it all, so any of us would be wasting our time if we tried to compete against each other,” Wiley said.

In fact, Chang recommends his clients advertise in print and radio at the same time, to get the most coverage for their events.

What’s tough for us, is with social media, and free Internet and websites, and all of that stuff, people feel they don’t have to advertise because they can get stuff for free,” Chang said.

It’s a timely problem, only one of many changes the three have seen in the media landscape over the years.

But, Wiley was quick to point out, “There will always be a need for storytelling.”

“I think the role of the media has a lot to do with the character of the island,” Fujimoto said. “And how we cover events, how we treat events, I think molds us to what we are.”

“One of the hardest things that I look at is that word ‘community.’ Everyone talks about aloha. But aloha is a given. Community … people use that word all the time, the mayor uses it at almost every event. Our bosses use it. But do they really know what it means? We are a community newspaper. Nobody has told us different. We’re a daily, but we are still a community newspaper. And so ‘community’ is everybody, whether it’s the kupuna who sits at Walmart or the kid who’s in preschool and even the ones younger than that. They’re all part of the community, and that’s their story.”

Changes, challenges facing Kauai

The three have a unique perspective on how Kauai has changed over the years — or not.

“To me, it really hasn’t changed as much as people give it credit,” WIley said. “We’re about five small towns; we have more traffic lights; we’re returning to the traffic situation we had before Iniki.”

When Wiley first moved to Kauai in 1989, he was asked by a TGI reporter what he thought of the traffic.

“And I’d just come from Honolulu, so I said ‘What traffic?’ And boy did I get slammed! ‘Ron Wiley thinks there’s no traffic here!’” he mimicked. “Never forget it.”

And traffic woes are minor compared to what Wiley sees as a more serious threat to Kauai.

“And that’s ice,” Wiley said. “The problem of ice and its related problems. That, to me, is the big thing. We still know each other, we still recognize each other in the post office, you still know people by face. It’s amazing, even though we’ve grown. It was 40,000 when I moved here, it’s now 70,000, but I’m saying it hasn’t changed that much.”

Chang said he’s been really blessed in that he hasn’t seen the influx of drugs.

“I guess I’m hanging around with the wrong crowd.”

But Wiley sees evidence when he goes to work at 3 a.m., drivers parked in a suspicious way, poised for a quick getaway; people coming into the station high, because the door is always open.

“Ice is actually a symptom,” Wiley said. “There are people who are without, and that gap has grown, and they have turned to ice, and that causes the gap to increase, because it wipes those people out financially, as well as their family, and so on and so forth. So if I were to say, the biggest change is we see the symptom of social problems, which is ice.”

But even so, he pointed out, crime is not as bad as it could be.

“Most of the time, the front page of The Garden Island newspaper doesn’t have a crime story to report!” Wiley enthused. “Not a real crime story anyway, not like you’d see in Honolulu. And that’s fortunate.”

Even though status doesn’t matter as much on Kauai as other places, Chang said, it’s clear from his work with the United Way that “it’s tough, financially and economically. … You can see a lot of strain on a lot of not-for-profits,” and lots of people are living paycheck to paycheck.

“And the sad part of it is, when you look around, look how blessed we are to live on this island,” Chang said. “When you look at all we have, when you look at the water, when you look at the mountains, you feel the air, you feel the rain, you see the sunrise, how do you not get high on that? People, for the most part, are happy!”

“Now that has not changed,” Wiley commented. “People have always taken what we have on Kauai for granted. And some have not! Many, many, many people, in the 25 years I’ve been on island, love and appreciate what’s here. There are a lot of people like that. And, there’s some folks who just don’t. And possibly it’s because they’re out of food. There are a lot of hungry people … I can see why they find it difficult appreciating the ocean,” and all the natural beauty of the island.

Chang is also concerned about social malaise.

“I don’t believe a lot of the local people feel like their voices are heard,” Chang said. “They don’t say anything generally to your face. It’s all in the garage or generally amongst themselves. Local style, you don’t say what’s on your mind until it’s too late and the natives get restless. But I just think, in my humble opinion, people gotta start waking up and taking control of what is going on in Kauai, for what I think is for the betterment of Kauai, but people don’t speak up. For lack of a better word, people will sit around and talk stink but don’t be proactive of what they know.”

Fujimoto missed that part of the group discussion, as he was out on assignment (”Got stuff to do!”) But he is optimistic about the state of the island.

“I don’t think we have any big challenges,” he said.

No complaints about traffic or drugs?

“You know, those are all problems that go back to that word, ‘community,’” Fujimoto said. “If that’s a problem, it means the community has a problem. Because what happened to tolerance? And patience? And helping?”

Overall, he says, life is good.

“You know, this is a great place to be,” Fujimoto said with a smile. “We live here and we make the best of what we got.”