‘Mick’ looks back on baseball career

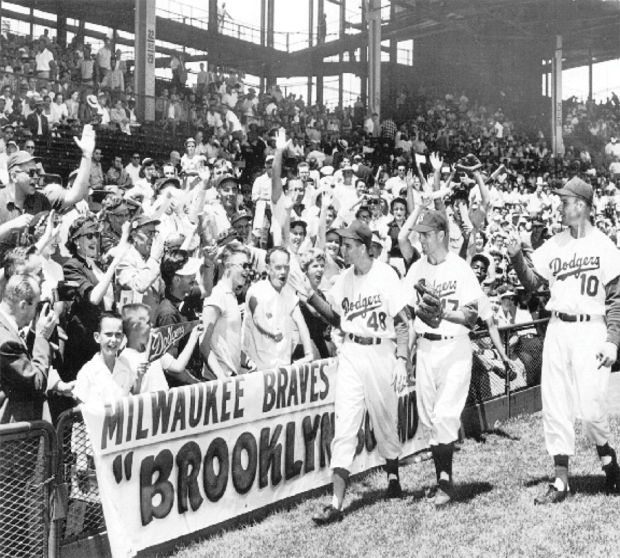

In the black and white picture, taken some 60 years ago, three members of the Brooklyn Dodgers, in uniform, are walking on the grass next to the stands of Ebbets Field. Fans are standing and cheering. One man is taking a photograph. One boy holds up a Dodgers pennant. A woman wearing a baseball hat with a “B” on it is waving and smiling.

It is one of those magical moments, a perfect summer day at the ballpark, captured on film that depicts the joy of the game. A glorious day of warmth and sunshine and these three ballplayers are on the receiving end of accolades and roars. They are Brooklyn Dodgers.

Glenn Mickens is one of those three players.

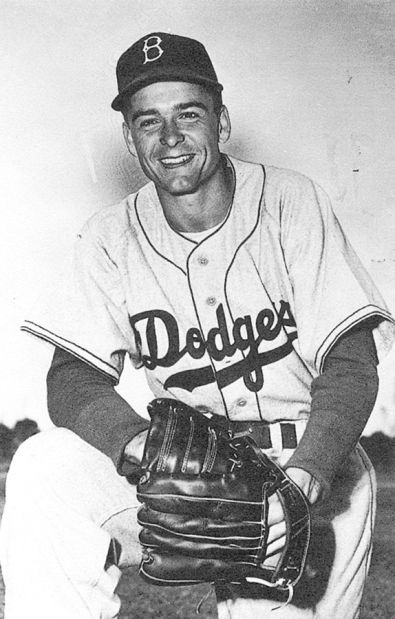

The 83-year-old today lives in Kapaa. He remains involved in youth baseball on Kauai, still follows the game he grew up playing, and yes, enjoys chatting about a career that saw him, at the age of 22, take the mound for the Dodgers in Ebbets Field in 1953.

He played with Jackie Robinson, Duke Snider and Pee Wee Reese, all Hall of Famers. He belonged to one of the best baseball teams in the world. And yes, it was unforgettable.

“It was wonderful, really wonderful,” Mickens said during a recent interview with The Garden Island. “I was fortunate.”

Mickens, who grew up in Los Angeles, had a sinking fastball good enough for the bigs. “Mick,” as he was called, pitched in several games with the Dodgers that year, as they won the pennant. But before the season ended, he was sent to the minors, and never made it back to the majors.

Still, he went on to compete and play with some of the game’s biggest stars, including Don Drysdale, Roberto Clemente, Tom Lasorda, George “Sparky” Anderson and Dick Williams. He went on to pitch in the Dodgers’ system for another five seasons and played five more in Japan. Later, he coached at UCLA for 25 seasons before finally retiring.

He loved the game then, and he loves it today.

How great was it to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers?

“I’m having the time of my life. I was 22 years old, the people are screaming, there’s people in the stands, a pop up goes into the stands, these guys are all wearing suits and tie, people didn’t come to games like they do today. You’ve always heard guys talk about it. At the time it’s going on, it doesn’t mean that much to you. You’re not caught up in the whole attitude of everything that was going on. And later on, you look back on it, every week I get two or three letters, sign this, sign that. I was a nothing in baseball, really. They send me pictures, they send me a bat to sign now and then. But when I look back, it really was a special time.

How much ball did you play growing up?

There were no little leagues or pony leagues. You just got together with a bunch of kids and played sandlot. We had fun. I think we had as much fun then as anybody did. My first organized baseball was American Legion when I was 16. Win or lose, they’d take us to a restaurant. You’d look at the right-hand side of the menu and pick out the most expensive food you could get. Oh, we had a great time. We were always throwing something, rocks and dirt clods, which strengthens your arm. Today, what are kids doing? They’re texting.

Did you play college ball?

I went to UCLA in the fall of 1948, made the team as a freshman and was a pitcher. I would have starved if I had to play anything else because I couldn’t swing the bat.

During that summer, I went to a Dodger tryout camp. They put these camps on all over and let anybody come who wants to try out. You run the 60-yard dash, they test your arm strength with a radar gun.

I drove to Anaheim for a week in a 1935 Ford convertible and I still have it. The Dodgers liked me because I had a natural sinking fastball. I said I was going to UCLA, and they said great. They gave me $20 for gas at the end of the week. When I went back to UCLA, after a few weeks of practice they said I was ineligible for college ball for accepting money from a professional team. I told them it was just for gas, but it didn’t matter.

In the spring of 1950 the Pacific Coast Conference voted 5-5 on giving me back my amateur status, but I needed a 6-4 vote. Since I couldn’t pitch for UCLA, I pitched for a semi-pro club in Los Angeles and threw a no-hitter that got a mention in the newspaper. Anyway, that got me into more trouble because they said I violated another college rule about not playing semi-pro ball during the season. It seemed doubtful I would get my amateur status back, and our athletic director suggested I try out for a pro team, so I did.

When did you sign with the Dodgers?

I tried out at Gilmore Stadium and they signed me that night. This was in 1950. They signed me for $6,000, with $4,500 in bonus and the rest in salary. I started playing in class C pro ball in Billings, Mont., where I was 6 and 4 with a good ERA in half a season.

In 1951 AA Fort Worth in the Texas League bought my contract and under manager Bobby Bragan I was 4 and 2 before I had to go in the army, the Korean War, for two years— 1951 to 1953.

I saved up my leave time and Dodgers manager Charlie Dressen, who remembered me from spring training in 1951, invited me to Vero Beach. In 15 innings against major league teams, I didn’t give up a run. The Dodgers had to keep me on their club and took me all the way north to Baltimore before I had to leave and go back to the army for my final 30 days. The Dodgers start spring training in Vero Beach and then move to Miami to begin their exhibition games. We went to Miami in a team bus and the first thing I vividly remember was seeing all my black teammates, Roy Campanella, Joe Black, Jackie Robinson, Don Newcombe and Junior Gilliam, in a car beside the bus. I asked Charlie why they weren’t on our bus and he said, “They can’t stay at our hotel nor eat at our restaurants — you are in the south now–these are the rules down here.” I was truly shocked, since I came from Southern California and never saw this happen. If you like someone, it is because they are good people or good ballplayers and not because of their color or race.

Maybe things could have been different for my career if I would have stayed with the Dodgers then.

Anyway, after serving my final 30 days the Dodgers sent me to Fort Worth where I was 8-5 in two months. They pitched the heck out of me down there. I made the all-star team had a 1.78 ERA in 138 innings.

What did you think of Dodger owner Branch Rickey, who broke baseball’s color barrier when he signed Jackie Robinson in 1947?

Branch Rickey was a true genius. I knew guys that went in to ask him for a raise and came out of there with a $100 cut and they’d still be happy. Ricky, he was the ultimate in showmanship and everything, but he had to pick somebody. He picked Jackie, who could not only be a great ballplayer, but could keep his mouth shut, which was the key. People yelled slurs and dirty remarks at him, and players slid at him and tried to cut his legs off. All these things, he had to put up with all that and still be a great ballplayer.

If you’re competitive you can play. You can do what they tell you to do on the ball field. It’s not your color. That’s crazy, complete idiocy.

When I came up in the minors, we had incidents of going into restaurants with black players and places refused to serve them. They were good ballplayers, good kids. In spring training in Florida, there were black restrooms and black drinking fountains. I said, “What’s this?” They said, “That’s the way it is in the South.”

How good was Jackie?

He was one of two ballplayers I ever saw who could take off to steal second base, know he was going to get throw out and go back to first base. His first step he was practically going as fast as he could go. Very few guys have that capability. It takes them three or four steps to get going.

To watch this guy play, the fire within him. A great guy. A wonderful individual. He had this fire, he was going to beat you. To be able to have this guy playing second base behind me, that was something.

How did it feel to be on the Dodgers at age 22?

I’m sitting there on the same team with the Boys of Summer. To be up there on the same club, pitching to Roy Campanella, Jackie Robinson playing behind me, Pee Wee Reese, Billy Cox, Gil Hodges. They were all good to me. They had fun with me. Carl Furillo in right field had an air rifle. I mean, he could throw. Teams there, they had 10 sports writers, they wanted all kinds of stories from different ballplayers.

How did you do when they brought you in to pitch?

The first time Charlie brings me in from the bullpen, we’re playing Cincinnati. He brings me into face Ted Kluszewski. Here’s a guy who had bigger arms than my legs. I’m looking at this big guy thinking, “What the heck, Charlie, what are you bringing me in against this guy for?” I get a couple of strikes on him, I don’t want him to hit the ball back up the middle, he’d kill me, so I pitch away. He hits one into the left-center field stands in Ebbets Field, probably took out about four rows of seats. I’m glad he didn’t hit up the middle.

When I got back to the dugout (teammate Johnny) Podres is sitting there laughing. He says, “Don’t worry, ‘Mick’, I throw from the left side and he’s hit five off of me.” I was up for 40 days. When I got up there, they got on a winning streak and they couldn’t lose. He was using me intermittently, started me a couple of games.

I started a game in Wrigley Field, Ralph Kiner hits one up in that jet stream, hits a home run off of me. The announcer says, “This was for his new baby boy, just born.” Twenty years later, I’m coaching his baby boy at UCLA, Mike Kiner.

“Mike,” I said, “You sent me back to the minor leagues because your old man hit a home run for you.” Mike was a good kid. Became an architect.

Where did your career go next?

At the end of that time, Charlie says, “Mick you want to play winter ball in Cuba?” I said, ”Yeah, what the heck. I haven’t been in pro ball a full year. I could use the experience.“ He said as a rule, you can’t be up here over 45 days or you can’t play winter baseball. I said, “Well, send me to Montreal.”

Ironically, they played in the World Series that year. I could have sat there on the bench that year and been on a World Series ballclub. But I didn’t want to be one inning here, one inning there. I needed the experience. I didn’t want to be on the bench, I didn’t care if the Dodgers, or who it was.

So I went up to Montreal and won a couple of ball games, played for Walt Alston, as a matter of fact. I was 2-0 up there, won a 1-0 playoff game. I did well. Charlie still liked me. In 1954, I had arm problems. They sent me to Fort Worth where it was hot. Something with my arm wasn’t quite right. I was supposed to be the ace of the staff, I was 1-10 at Fort Worth.

At the end of that year, they sold my contract to Montreal. In 55, I had my best year in baseball. I was rooming with (Don) Drysdale he was 11-11 that year, I was 12-3. I relieved all year until Drysdale got hurt, so I started my last four games of the season, I completed them, I won all four games, ended up with a 2.18 ERA, We won the international league pennant by one-half a game. I had a great year, but the Dodgers wouldn’t give me another crack. They had this stupid reserve clause at the time, you either played for the club they told you to play for, for whatever price they told you to play for, or you carried the lunch pail.

I did everything I could. I begged the Dodgers, “Play me, sell me, give me away, I want a crack with another club.” Ralph Kiner was a manager with the San Diego ballclub in the Pacific Coast League. I called him one day, “You remember me? You hit a home run off me for your kid that day. Can you get me into your organization?” He said, I’ll see what I can do here. He called me back, “They won’t let you go.”

So you went to play in Japan for five years. How was it there?

They treated me real good over there. Hundred stories I could tell you.

I was on the worse defense and worse offensive club in the league. They hadn’t been out of the cellar in 10 years, and I didn’t know that. I was on three all-star teams. I got to face Sadaharu Oh once or twice. He had that big leg kick. He hit the ball hard to left field, I got him out OK.

What were the highlights of your career?

Signing my first pro contract to get into baseball. I’m an adult playing a kids’ game, having fun, having the time of my life. Even the bus trips in the Pioneer League, 750 miles, Boise, Idaho Falls, Pocatello, Salt Lake, Ogden, Great Falls, Billings, traveling on the bus, I’d stay awake all night. It was just a different world for me.

How hard was it to finally gave up baseball?

I was 35 and I wanted some kind of security, and you had no real security in baseball then. There was no pension plan or anything. During the off-season, I was working on a freeway in Los Angeles with a pick and shovel. I had more benefits for me, my wife and my family then I had as a professional ballplayer. Even with all that, I wouldn’t change a minute of all the time I spent in baseball. It was a great ride.