Talk Story with Stu Burley

PACIFIC MISSILE RANGE FACILITY – In 1957, Elvis Presley was leading a musical revolution and had yet to be drafted into the Army, “I Love Lucy” was the most watched show on television, Dwight D. Eisenhower began his second term as president, the Soviet Union launched the first satellite into space and Hawaii was still two years away from becoming a State.

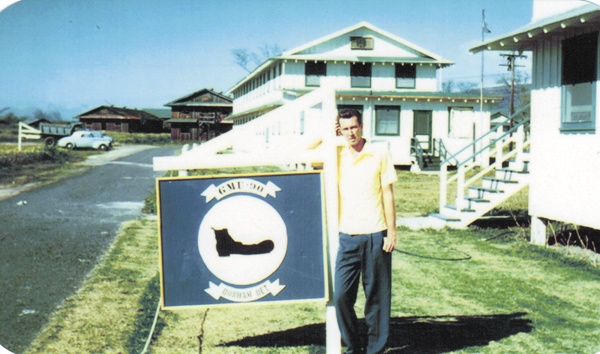

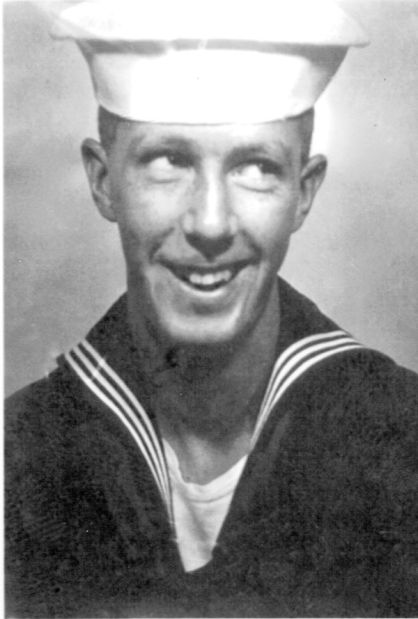

And on Jan. 4 of that year, the first contingent of Navy personnel arrived at Bonham Field, Barking Sands (the precursor to Pacific Missile Range Facility). Among that initial group of seven was a tall, young seaman apprentice (E-2) from upstate New York named Stewart Burley – and he’s been here ever since.

From 1957 until his retirement from civil service in 2004, Stu (as he’s more commonly known) was a sailor, a contractor and a government service employee at Barking Sands. These days, as the president of the Navy League’s Kauai Chapter, he’s still very much a presence at the base – he’ s attended every single one of the 25 change of command ceremonies for the base’s commanding officers and continues to observe major Missile Defense Agency launches from the range.

He’s literally a walking, talking history of the Navy’s earliest days at Barking Sands and the service’s evolving mission in testing and training. Many of the programs which he helped bring here through marketing the range’s assets during his tenure as a supervisory program analyst.

But back in ‘57, there was only a runway surrounded by a vast expanse of ocean and a lanky, displaced sailor with a vision.

“My dream, for the longest time, has been to launch a satellite out of Hawaii,” he said. “And of course it should be launched out of PMRF because we have range safety, radars, telemetry… we have it all.”

It all started with the Regulus missile operations that Stu and the first group of sailors came in to set up. He was a guided missileman – “the elite of the Navy they called us.”

But when they arrived, there was “nothing out here. They had to fly in our food daily from (NAS) Barbers Point (on Oahu). There was one Air Force major here who was like the caretaker of the facility,” he recalled. “That’s why we have ‘Major’s Bay’ out here (the recreational area), named because of that Air Force major.”

“Anyhow, we were preparing the Regulus missile for launch from here,” he continued. “Those launches came off the submarines from down near the Big Island back then, and we’d remote control fly them up here to land on the runway. In fact, the blue missile that’s out front (of the north gate) had either nine or 11 flights because these were practice Regulus missiles.”

The submarines would surface, he explained, launch the Regulus and “it would come all the way up through the Hawaiian chain at 35,000 feet. There was usually a chase airplane following it. Then we’d land them on the runway. Of course, there were a couple of them that we crashed on the runway back then.”

“As a guided missileman, I did… well, everything,” he said, only half-joking. “We did all the electronic packages, the telemetry packages, the dump system, the airframe, the tires, the boosters… in addition to working on control and range safety. We were on the flightline too, running the firefighting ops when Air National Guard planes would come in.”

And as missile operations were in their infancy, so were the associated protocols.

“Nowadays, for range safety here, we have aircraft that go out and look around, boats that clear the water, radars looking out there… back then when we’d go to launch, we’d just stand on the end of the berm in front of the launchpad like this (simulating a hand over his eyes and peering into the distance), ‘Okay, good to go!’ (signaling thumbs up) and ‘BOOM!’ right out over the top of us.”

Something else that isn’t done anymore but that was relatively commonplace back then was “hitchhiking” at the end of the runway, according to Stu.

“I used to go back and forth to Oahu,” he recalled. “I’d hitchhike on the Coast Guard C-130. I remember one time I was at Barbers Point coming back and I was out on the runway in a pair of rubber slippers, short pants, tank-top shirt and my little duffel bag with my thumb out. Of course if you try to do that today, they’ll put you in jail. So this plane stops and a guy gets out and asks ‘Where you going?’ ‘I need a ride to Bonham,’ I told him and he said ‘Come on, we’ll take you.’

“Well, we get over here and land and they tell me ‘You have to get off the back. We’ll lower the back.’

‘Can’t I go out the door?’ I asked. ‘Nope, it’s broken.’ Well, OK, so they lower the back of the aircraft and I go walking down the ramp and there’s six side boys all in whites saluting me and there’s the commanding officer and I’m like ‘Oh, hi guys,’ and the CO yells ‘Burley! What… what… what are you doing? Get in my office!”

“I guess the Coast Guard guys were having a little fun and had called ahead and reported that they had an admiral on board and the admiral wanted side boys for his arrival. I could hear them laughing up a storm inside.”

In 1959, when his enlistment was up, Stu wasn’t sure what he wanted to do, but he said he was having fun in the Navy and was dating a local girl, so he extended a year. And after that year, he wound up staying yet another year at Barking Sands, until finally separating after six years of service in 1961. By then, he was married and not looking to leave Kauai.

“My wife …” he recalled with a smile, “she picked me up one day and bought me a beer and a hamburger. Six months later we were married.”

Her name was Kuuipo Gail Kaiwa from Kekaha and they were married 51 years, until she passed away last year. Through marriage, Stu extended his association with the base at Barking Sands.

“Her dad was the public works foreman out here during the war and he named all the streets on the base,” he said. “His parents were born at Barking Sands, lived all their lives here and are buried on Barking Sands.”

After leaving the Navy, he found a temporary job on base as a supply stockman at $50 a week. Then he heard of an opening for the operations coordinator position (equivalent to the current range operations officer). There was a lot of technical writing involved as part of the job and Stu told the hiring authorities, “Hey, I can do that.”

“They were like, ‘Really?’” he remembered. “This was on a Friday, so I said, ‘Yep, Monday I will come in here and write a technical report for you.”

At that time, there was a technical writing program in Honolulu, so Stu called them and said he needed their course book rushed to him right away. He got it on a flight that evening and spent the entire weekend studying it.

“So I went back in Monday,” he said, “and they asked me to write a technical report on something. Well, I just read the whole manual, so I said ‘Piece of cake.’ Knocked it right out and they said ‘Whoa, you’re hired.’ So I became the ops coordinator. So I went from supply stockman, which is the lowest guy on the totem pole, to way up there in charge of everything – every operation, every launch, every mission we did. I mean, we had a general manager, but I came right under him as a civilian contractor. All of the sudden I’m coordinating operations, timecards, work schedules…”

In 1968, the Navy created the range scheduling officer position and Stu moved into the civil service career field to fill that job and the role of program manager for fleet operations.

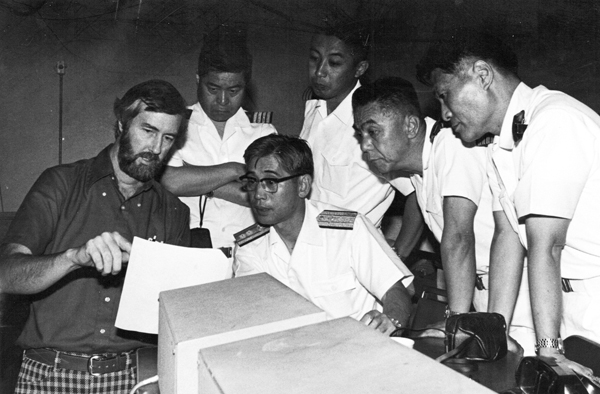

During the next 20 years, he would be instrumental in shaping the course of PMRF. He helped establish the first underwater range in the Pacific, he became program manager for submarine operations and initiated the “Hollywood” series of submarine commanding officers qualifying courses conducted semi-annually off PMRF, and he kicked off “some little” fleet exercise called Rim of the Pacific in 1971.

“They asked me if I wanted to be program manager for this thing they were putting together called RIMPAC, so I said ‘Sure, why not?’” He recalled. “I started that by getting New Zealand and Australia involved, along with the U.S., United Kingdom and Canada for the first one.”

RIMPAC has since grown to 22 nations as of the last exercise in 2012. It’s held biennially in June and July of even-numbered years and is the world’s largest international maritime warfare exercise.

Despite all of those accomplishments, he never lost sight of his dream to launch a satellite into space from PMRF.

“I went to Senator (Daniel) Inouye and I asked him, ‘Can you fund a satellite launch facility?’ He said he couldn’t do it because he couldn’t give that many millions of dollars to one organization. He told me to wait until I got out of the (employ) of the Navy and talk to him again.

The intervening years from 1994 – 2004 kept Stu busy as not only PMRF’s supervisory program analyst and head of the fleet division, but also taking on the responsibilities of the newly established director of marketing to support business development and bring new customers to the range, such as MDA and the Aegis programs.

Since his retirement almost 10 years ago, he’s kept active and kept pursuing his dream through involvement as an associate director with the Hawaii Space Grant Consortium and the Hawaii Space Flight Lab, as well as being appointed to the Governor’s Aerospace Advisory Committee, while founding his own consulting firm Strategic Theories Unlimited (with the appropriate abbreviation of STU).

He remembered Sen. Inouye telling him to come back and see him about the satellite idea after leaving government service, so he did.

“When I retired, I asked him again and he said, ‘Well, I can’t just give you the money, we’ll have to get a sponsor.’ So he looked around and finally decided we’ll go through the University of Hawaii, so he started to fund them and the dream started to come true.”

That dream looks to become reality next spring when UH in conjunction with NASA plans to launch a micro-satellite from the launch pad being constructed at PMRF’s southern end as part of the Super Strypi program.

So, through seven decades since the Soviet Union sent the first satellite into space and Stu Burley first arrived at Barking Sands, a satellite will be going up from the place Stu helped position toward that goal. Rest assured, he’ll be here to watch.

• Stefan Alford is public affairs officer with the Pacific Missile Range Facility.