Filipino-American History Month

LIHUE — From the immigrant bachelor cane laborers in early 1900s, the Filipino immigrants have blended with the island culture while maintaining their own proud history and cultural identity.

October is Filipino American History Month, a tradition started by the Filipino American National Historical Society in 1988. The California and Hawaii state legislatures soon recognized the month, and the U.S. Congress made it a national recognition in 2009.

“Filipinos are an integral part of our island community, and have enriched our lives through their culture and heritage and countless other ways,” said Kauai Mayor Bernard P. Carvalho, Jr. “It is truly fitting that we honor them by celebrating October as Filipino American History Month.”

Kauai Filipino Community Council President Charlmaine Bulosan said that families and village communities celebrated cultural and religious traditions in the Philippines and continued these traditions in America. This is part of how children learn about their heritage and carry it forward to the next generation.

“They need to learn more about the homeland — where their parents and grandparents came from,” Bulosan said.

Bulosan’s father, the late Capalino Suero, worked for the HSPA and was active in the community with his own radio program. She said that as a child she didn’t understand why her parents brought her to all those events, but that in hindsight it taught her about community building.

“My father’s involvement in the community was to help the immigrants who came to Hawaii and Kauai, and if they needed help translating documents or easing into the island life and the American way, he was there to help,” she said. “As I got older and got married, I saw the need to give back to the community and it helps to have parents like that to get adjusted.”

Filipino History Month recognizes the contributions of the community, and how far they have come.

The message is also not to sit back and watch, but to get involved with the community.

The Kauai Filipino Cultural Center project underway is one way to unify the various regional and ethnic groups from the Philippines. They can share the celebration of their respective events with the wider Filipino and Mainstream communities, she said.

“It is so nice to have these different groups that all have their own pageantry and way of celebrating and expressing their traditions,” she said.

The Filipino Community Council sponsors the annual Miss Kauai pageant and Bulosan said the winners usually stand out for their cultural knowledge. Most know very little about their heritage, she said. The dances and songs are part of it but there is much more that, in a larger scope, forms the culturally based values that parents pass on to their children.

Miss Kauai Filipina 2013 Kayla LeAndra Dela Cruz-Cadavona said Filipino American History Month reminds her that living in the United States makes if possible to acknowledge her Filipino and Ilocano-heritage.

“Filipinos migrated to the United States for a reason, and that’s to find better opportunities for themselves and their families back home,” she said. “In that, however, I feel we’ve lost a sense of cultural identity because of our upbringing in the states or the idea of ‘F.O.B.’ (fresh off the boat) as a derogatory term. I want us to remove ourselves from that and realize that for us to tap back into learning about our history and sharing it with others will be a truly worthwhile experience.”

Filipinos appear in North America as early as the 16th century as sailors aboard Spanish galleons that jumped ship. They were forming communities in Louisiana by the 1700s. The Hawaiian immigration began in the late 19th century when the Hawaiian Sugar Planters Association (HSPA) sought young, single men from the Philippines.

They were considered strong and productive and as imported workers they were also vulnerable to exploitation, said Roderick Labrador, an ethnic studies professor at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

To understand the Filipino-American experience, it is necessary to get past the “colonial amnesia” regarding America’s history with the Philippines and Hawaii, he said. Filipinos were U.S. nationals after the Philippine-American War until Commonwealth status in 1935, but a strong HSPA lobby kept Hawaii exempted. The War delayed immigration until 1946 when thousands of Filipino men and women started coming to Hawaii.

“The Filipinos have different kinds of immigration trajectories,” Labrador said.

During World War II, the 1st and 2nd Filipino Infantry Regiments were formed as a segregated U.S. Army unit of 7,000 Filipino Americans. Filipinos in Hawaii were needed as sugar laborers and fewer than 500 were allowed to enlist in the 1st Regiment and only after 1943.

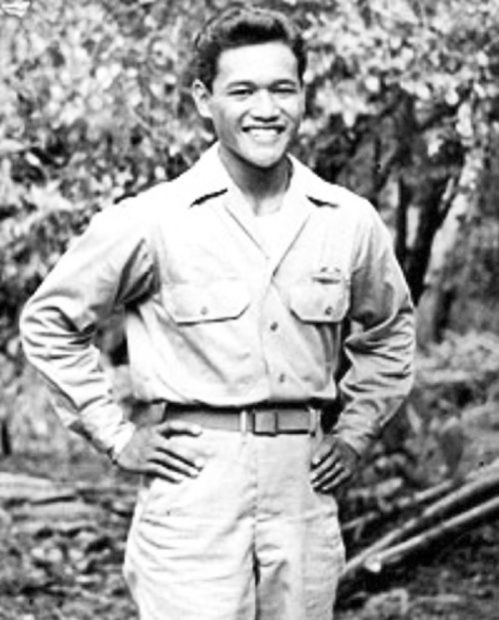

Kalaheo native Domingo Los Baños would stop working at his father’s plantation store to enlist with the 1st Regiment. His four brothers would also join the Army.

He said the Filipino scouts were the “eyes and ears” for General Douglas MacArthur and provided intelligence on Japanese troop movements. They would help liberate prisoner or war camps and free the Bataan Death March survivors.

There are only about 40 of Fil-Hawaiian soldiers of the 1st Regiment still living, Los Baños said. He helped to fund the documentary film, “An UnTold Triumph” to make sure their contributions did not go missing in history.

Los Baños would go on to earn a master’s degree from Columbia University after the war. He taught school at Waimea and Kapaa before becoming principal of Anahola School.

Recalling that he was at one time the only male Filipino teacher in the state, Los Baños said he was reminded of how far the Fil-Americans had come recently at a conference. He sat with a group of Fil-American educators and paused to thank them for the work they do.

“I said, ‘You make all what they (the 1st Regiment) sacrificed for during the war mean something,’” Los Baños said.

He also reflected on the values learned from growing up in the camps, where “a community of old men who were kind and faithful to the parents and exhibited an esprit decor.”

The Filipino bachelor laborers didn’t have families or the same kind of attachments to Hawaii as other immigrants, Labrador said. They would begin to marry in their older years after the immigration laws changed in 1946, and this unusual marital dynamic within the plantation structure became the ‘uncle’ and ‘auntie’ kinship network.

District 15 State Rep. James Tokioka said those first “sakada laborers” would add up to 10,000 migrants in the state by 1920. They formed the foundation of what became Filipino communities near the Puhi and Hanamaulu sugar mills.

“Although early migrants were unable to bring their wives and families with them, these brave, dedicated and hardworking individuals brought a new culture to our islands that was all their own,” Tokioka said. “The music, dance and undoubtedly the food that is at the core of the Filipino culture has enriched our island and our state, and has seamlessly complemented the unique blend of cultures that makes Hawaii so very special.”

The Filipino community comprises 12,108 of Kauai’s 67,091 population and is the largest minority population group, according to the 2010 U.S. Census. Only the Caucasian and the two-or-more race categories are larger.

These numbers helped to distinguish Kauai as the Hawaiian county to elect a Fil-American as its mayor in 1974.

Eduardo Enabore “Mala” Malapit served eight years on the Kauai County Council before elected mayor and would serve four terms before stepping down. He died in 2007.

The continuing immigration of Filipinos with the integrated island communities create a mix of people who identify with the Philippine experience and others who see themselves as Hawaiian-Filipinos, Labrador said.

The Filipino cultural centers in Waipahu, Maui, and Puhi, are in part to recapture a sense of shared identity especially among the younger generations, in a positive way to avoid a distancing from their culture caused by assimilation and negative immigrant stereotypes.

“A lot of folks will tell you there is nothing wrong with becoming local, and to a certain extent they are denying a sense of being Filipino,” he said.

The Kauai Historical Society maintains a collection of resources for families looking into genealogy at the County Building. Plantation payroll records and bango cards offer tidbits of family history such as birth dates, employment start and end dates, residences, and sometimes a bit of good or not so good family or work history.

“We have a lot of information here including old phone books, manuscripts, photos, maps and recordings, said Malina Pereza, a KHS archivist. “Come and check it out and maybe find something that you were looking for and never knew was here.”