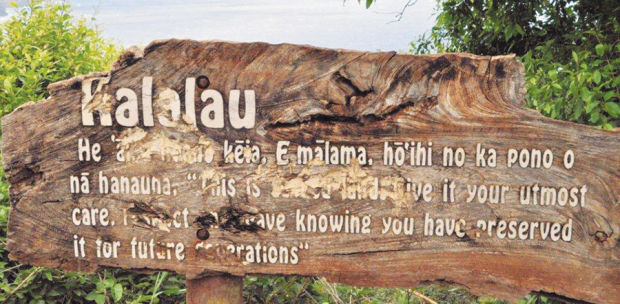

Kauai’s Kalalau Trail is no stranger to heavy foot traffic or Top 10 awards. It has been included among the World’s Best Hikes, America’s Most Dangerous Hikes and Scariest Cliff Walks. And earlier this year, USA Today ranked the Na

Kauai’s Kalalau Trail is no stranger to heavy foot traffic or Top 10 awards.

It has been included among the World’s Best Hikes, America’s Most Dangerous Hikes and Scariest Cliff Walks. And earlier this year, USA Today ranked the Na Pali Coast as one of the “10 Most Beautiful Places in America.”

Although nothing short of spectacular, the Na Pali Coast State Park — home of the Kalalau — is also a persistent headache for the state Department of Land and Natural Resources.

“Kalalau is a large and remote location which is costly and difficult to monitor, maintain and enforce on a regular basis,” said Deborah Ward, information specialist at DLNR. “And it also offers many hiding places.”

Each year, large numbers of residents and visitors flock to the coastal trail, some for the short two-mile jaunt from Kee to Hanakapiai Beach, others for the 11-mile haul out to Kalalau Beach.

Then there are those who get to the tail’s end by boat — sometimes via illegal transport operators.

With the packs of visitors come trash and a lack of proper camping permits. In fact, the number of unpermitted campers frequently exceeds the permitted ones, Ward said.

Due to the uniqueness of the park and the large investment backpackers and paddlers make getting there, Ward said DLNR receives a greater number of pre-trip inquiries and post-trip complaints compared to other parks in the state.

Chronic problems include illegal camping, leftover rubbish and damage to ecosystems, according to Ward. And while there have been possible occurrences of theft, no formal complaints have been filed.

Then there is the damage to archeological sites by squatters, including moving foundation stones, building fires and excavating for gardens — activities Ward said “may end up destroying the very evidence we need in order to definitively date the sites in the future.”

Matthew Gilgan, of Ontario, Canada, described his recent experience into Kalalau as disheartening and disappointing. Gilgan had been visiting Maui with his wife and child when he decided to take a vacation to hike Kalalau alone.

While the trek itself was spectacular, he said the scene at the trail’s end was “crazy” — dozens of boats parked offshore, piles of trash and abandoned camping gear, loud helicopters buzzing overhead and upwards of 150 unpermitted campers on the beach.

Gilgan said he came to enjoy the solitude of what is supposed to be an “isolated gem,” but found something very different.

“You come to kind of get this peace and quiet and it’s just people sprawled all over,” he said. “There’s just no place to go and find some quiet.”

Ward said common activities at the beach — illegal boat transport operators yelling at people early in the morning, late-night drum circles and naked yoga fronting the campsites — “can be offensive and certainly take away from the serenity one normally expects” within backcountry and wilderness areas.

Kauai resident Kurt Bosshard, who has hiked the 11-mile trail dozens of times, said the problem is not the campers, and that year after year the state continues to make a big deal every time it has to haul out a load of trash.

While the toilets can be gross, trash does tend to pile up and it’s not uncommon to meet someone who has been camped out for several weeks or months, Bosshard said he believes the biggest problem in the Kalalau Valley is the degradation of historical sites by invasive plants and animals.

“The place has been abandoned to the ruin of these invasive species,” Bosshard said. “(DLNR) always want to point the finger at the campers, and the campers have almost no impact on the valley.”

Over the 20-plus years he has been hiking the trail, the situation has remained the same — a park functioning as an “abandoned place of extreme beauty” instead of a park, according to Bosshard.

“It’s a problem without a solution,” he said. “It’s a bunch of everything — some good, some bad. We don’t have the resources to change things.”

The number of permitted campers at Kalalau averages 60 per day, or more than 20,000 per year, according to Ward. In 2003, the DLNR estimates 537,000 hikers and campers took to the trail. In 2007, the number was 423,000.

“We have had individual day counts of over 2,000 hikers entering the Kalalau Trail,” Ward said.

DLNR’s Division of Conservation and Resource Enforcement (DOCARE), the agency in charge of daily enforcement and maintenance, conducts periodic operations to remove illegal encampments and trash, and cite illegal campers.

“DOCARE has been sending officers to conduct enforcement sweeps utilizing State Parks helicopter blade time when Parks goes in to conduct maintenance and cleanup,” Ward said. “This summer two enforcement sweeps were conducted and 34 citations were issued.”

An additional sweep was conducted in September following an accident in which a private helicopter performing contract work for DLNR had a tarp blow into the rotor blades, damaging the aircraft.

Bosshard maintains that the DLNR simply doesn’t have the resources to maintain the park the way it should.

Ward agreed that resources are limited. Rather than focusing on more regular maintenance activities, workers have had to devote their time to collecting and hauling away trash and even human waste, as the composting toilets are sized only for legal camper capacity.

The ongoing issues involving illegals ultimately take away from time that could be spent on other critical maintenance and management activities, she said.

“We realize that one major shortcoming is the lack of continual or sustained presence in the park and on the trail,” Ward said.

To help out, DLNR’s Division of State Parks recently hired a full-time interpretive ranger for Haena-Na Pali. The ranger’s duties will be concentrated within the first two miles of the Kalalau Trail.

“It is anticipated that this ranger, among other duties, will be able to spot check for permits,” Ward said.

In the meantime, Gilgan said he has no intention of returning to Kalalau.

“Shame on me for going all the way out there to get my little slice,” he said, adding that a place as beautiful as Kalalau Beach should be cherished by locals and visitors alike.

“Seems some people weren’t doing their part to take care of what was there.”