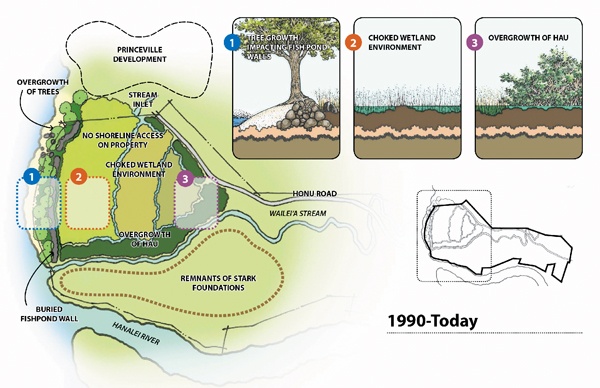

On the eastern edge of Hanalei Bay, next to the St. Regis Princeville Resort, lies a hidden piece of ancient Hawaiian history — the remnants of a 600-year-old fishpond.

The kuapa rock wall, now mostly buried by sand and thick vegetation, is about 1,000 feet long, 20 feet wide and was built around 1400 A.D.

“It’s almost certainly the largest wall on the North Shore of Kauai,” said Hallett Hammatt, a 40-year archeologist and the founder of Cultural Surveys Hawaii, Inc.

Hammatt first encountered the fishpond in 1982. Years later, he later took core samples from the existing wetland and discovered coral, indicating that the area was once a small inlet of Hanalei Bay.

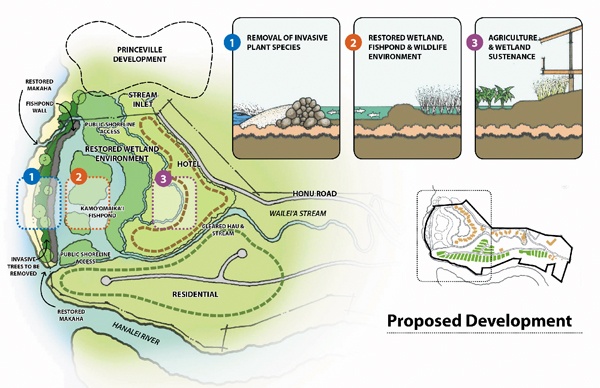

As part of its proposed Hanalei Plantation Resort, Ohana Real Estate Investors, LLC — owned by eBay founder and billionaire developer Pierre Omidyar — plans to revitalize Kamoomaikai Fishpond, now home to a degraded, 13-acre wetland marsh overgrown by invasive plants.

“The idea is to do what can be done to clean up the marsh, make some open water and start the process of getting a little bit of salt in there, brackish water in there, and cleaning up the flow,” said Hammatt, who was hired by OREI in 2010 to do an archeological survey.

OREI is expected to finalize its environmental impact statement later this summer.

Provided that all permits are approved, Michelle Swartman, OREI’s director of land and community development, said construction could start as early as 2016.

The entire project, including the development of the adjacent Hanalei River Ridge, would cost about $160 million, Swartman said.

When finished, OREI says the fishpond will compliment the rest of the development, improve water quality within the nearshore fishery and provide habitats for endangered and native species.

A typical developer might be quick to pass up such a project, because of its high cost and complexity, Hammatt said. But he says there seems to be a “real strong commitment” by OREI to do the right thing.

“I think they’ve gone way, way over what people normally do, because of the uniqueness of the place,” he said.

There is, however, a long and growing list of people who argue the developer has no intention of doing what is right for Hanalei, especially on the ridge above the Hanalei River and Black Pot Beach Park. There, OREI has plans for 34 residential lots, ranging in size from 15,000 to 20,000 square-feet each.

To date, the Hanalei Bay Coalition has gathered more than 6,000 signatures against the development.

Hayley Ham Young-Giorgio, a coalition member and founder of the community-based organization Save Hanalei River Ridge, said local opposition has little to do with OREI’s plans for the fishpond or even the 86-room, bungalow-style hotel around it.

“Our focus is to preserve the ridge, that river mouth and that whole environment,” she said.

Ham Young-Giorgio said she and many other community members feel the fishpond is being used as a “bait and switch.”

“It’s not a trade off — we’ll restore the fishpond and everything is fine,” she said.

Swartman said it is not a distraction, but rather, one component of OREI’s larger vision.

“We create destinations that find balance between the environment, the community and host culture within a resort setting,” she said.

Coalition member Carl Imparato said OREI is diverting attention from the Hanalei portion of the development and that sacrificing Hanalei’s beauty in return for a fishpond would be no different than allowing for the construction of a hotel on Kalalau Beach.

“OREI could promise to revitalize 1,000 fishponds, but that still would not make it acceptable to destroy Hanalei’s unique character and beauty,” he said.

Another major concern, Ham Young-Giorgio said, is that the developer is not planning to restore the fishpond for human consumption — its main historic function. In the end, she said it will be nothing more than a “water feature” for hotel guests.

“They’re building their hotel around a marsh and they have to make it look pretty in some way,” she said. “A quote-unquote ‘fishpond’ is a good solution for them.”

Fern Rosenstiel, an environmental scientist and marine biologist, compared it to reopening a historic restaurant and not serving food.

Hawaiian aquaculture specialist Graydon Keala, who has been involved with fishpond restoration and revitalization efforts since 1983, said Kamoomaikai Fishpond is a “historic relic” and that many lessons can be learned from bringing it back to life.

Although it would not be open for commercial use, OREI maintains the fishpond would provide cultural and educational opportunities for residents and visitors.

“For me personally, bringing a fishpond back to life. Wow. That is a plus back to the environment that goes on for a long time,” Keala said. “And it’s a sustainable thing. You just have to maintain the features of it and it will work its magic for the benefit of the people.”

Without OREI, Keala fears the area will likely remain as is — degraded and forgotten.

Coalition member Makaala Kaaumoana disagrees.

She said Kamoomaikai is one of three fishponds in the Hanalei area — part of a much larger aquaculture system — and never stood alone or functioned independently. The two others are in the process of being restored and Kaaumoana said it is only a matter of time before Kamoomaikai follows suit.

“It will be restored, and we don’t need a mediary to do it,” she said.

Kaaumoana added that the HBC has consulted with a number of its own fishpond experts, many of whom were brought to tears because they felt the fishpond was being used.

“That fishpond is not a flag to wave,” she said. “It’s not a toy. It’s not a commodity to be discussed as a trade. It has a completely different role than they are giving it.”

OREI maintains the revitalization “presents a number of opportunities to benefit the environment, culture and people of Kauai.”

Local resident Adam Asquith, who has worked as a research biologist for the University of Hawaii, a conservation biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and a wildlife biologist for Kauai National Wildlife Refuge, said OREI could completely avoid the project, if they wanted to.

“Honestly, that’s probably the smart thing to do because, as we’ve learned, any time you do something, particularly in a wetland. In these situations, it’s a commitment into perpetuity,” he said.

Whatever OREI agrees to upfront, Asquith said, will only be the beginning.

“It’s not just the upfront cost and upfront effort. It’s a commitment to the life of the land,” he said.

Asquith agreed it is unusual to find a developer willing to tackle such an undertaking. So far, he said he has been impressed with OREI and its vision.

Hammatt said the goal, in his mind, is to turn something that is not usable into something that is — to make something that is inaccessible, accessible.

But Kaaumoana, Imparato and Ham Young-Giorgio say they will not be fooled by what they believe are false promises.

“Restoration? Sure, it would be a nice thing,” Imparato said. “But the price that they are demanding is far too high.”

“It’s the last buffer zone between Princeville and Hanalei,” Ham Young-Giorgio said of the ridge.

In the end, Kaaumoana says a fishpond is not worth the destruction of one of Hawaii’s most scenic viewplanes.

“Hawaii is to pay for this promise, or for this promotion, or for this potential offer,” she said. “I have absolutely no confidence that that fishpond is anything other than a way to influence and divide thinking about what the development would actually do.”

The site location is home to the former Hanalei Plantation Hotel — built in the 1960s — which later became Club Med hotel. In the 1980s, developer Bruce Stark got approval for a 204-unit hotel but never finished construction.

“The new project will strive to minimize impacts, while creating a viable wetland ecosystem that contributes toward a healthier Hanalei,” states Hanalei Plantation Resort’s website.

• Chris D’Angelo, environment writer, can be reached at 245-0441 or cdangelo@thegardenisland.com.