HONOLULU — An expedition launched to track the drift of tsunami debris is using remote sensing to compare the actual event to computer predictions of the trajectory while improving officials ability to warn residents about impending landfall, according to a

HONOLULU — An expedition launched to track the drift of tsunami debris is using remote sensing to compare the actual event to computer predictions of the trajectory while improving officials ability to warn residents about impending landfall, according to a University of Hawai‘i news release Wednesday.

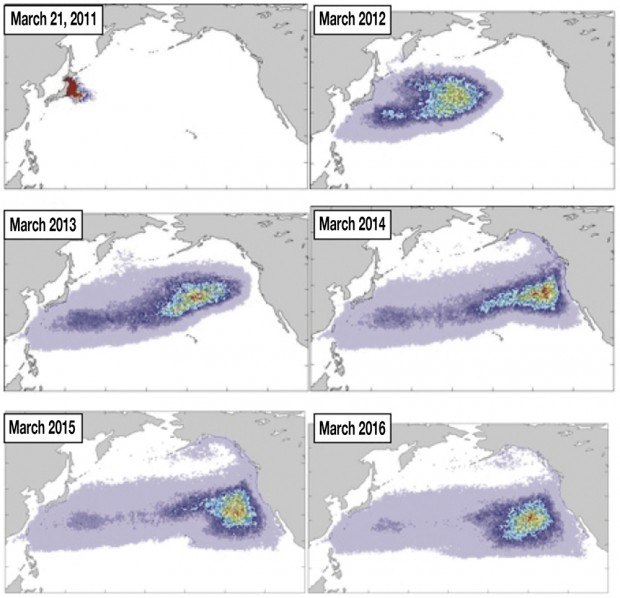

The tsunami that followed on the heels of the March 11 earthquake in northern Japan produced as much as 25 million tons of debris. Much of the debris was swept into the ocean.

What stayed afloat drifted apart under the influence of winds and currents, most of it traveling eastward.

Predicted to reach the west coast of the United States and Hawai‘i within the coming years, the debris’ composition and how much is still floating on the surface are largely unknown.

One thing is certain, however: The debris is hazardous to navigation, marine life and, when washed ashore, to coastlines.

Expedition launched

to track debris

To track where this debris is headed and provide appropriate warnings, a team of scientists and conservationists from the UH Manoa and Hilo campuses, Scripps Institution of Oceanography and the Ocean Recovery Alliance quickly created a plan to survey the debris field and mark it with satellite-tracked drifting buoys.

Contributing their expertise to the effort are two UH participants, International Pacific Research Center Senior Researcher Nikolai Maximenko and Scientific Computer Programmer Jan Hafner.

The team launched an expedition at the end of November from Honolulu to Midway Atoll and beyond.

Armed with equipment shipped from California by Horizon Lines, navigational software provided by Nobeltec, a computer model of probable trajectories and observations of actual debris by Russian training ship crew, the team surveyed the probable pathways of tsunami debris moving toward the Northwest Hawaiian Islands.

The expedition deployed 11 drifting buoys, designed to simulate the motion of different types of debris, in a line between Midway and the leading edge of the tsunami debris field. Data from these satellite-tracked drifters, used in conjunction with computer models, allow remote monitoring of the movement of the debris field, giving scientists and operational agencies a better awareness of the status of the debris field and of the region s current system.

Four hundred numbered wooden blocks were also deployed along the route, often near floating objects. Boaters, fishermen and beach-goers who find the blocks and contact the scientists as instructed on the blocks will help increase understanding of the motion of debris and currents in this region.

Henry “Hank” Carson, a UH Hilo postdoctoral scientist, is coordinating the wooden block information collection.

Debris passing north of Midway

Among the most important results of the expedition to date is the recognition that tsunami debris has recently not advanced toward Midway, but instead has been flowing eastward well to the north of the atolls.

Analysis of the ocean-current field shows why. In recent weeks, the general flow around all Hawaiian Islands has been from the southwest, producing a front located 300-400 miles northwest of Midway. This front and associated northeastward jet keeps the tsunami debris north of the islands — at least for the time being.

Although this flow has prevented tsunami debris from approaching the islands, it carries a lot of “ordinary” debris (mainly old plastic) from the oceanic garbage patch located between Hawai‘i and California. The expedition documented 175 such objects, many photographed and collected for examination.

Visit the tsunami debris tracking project at www.oceanrecoveryl.org for more information.