LIHU‘E — Marine experts are saying limitless $50 permits with few restrictions on species and size and no limits on take is allowing collectors to raid Hawai‘i’s reefs — bringing staggering consequences. Every 22.5 seconds a fish is taken from

LIHU‘E — Marine experts are saying limitless $50 permits with few restrictions on species and size and no limits on take is allowing collectors to raid Hawai‘i’s reefs — bringing staggering consequences.

Every 22.5 seconds a fish is taken from the state’s reefs. That’s 160 fish per hour, or 3,840 per day, according to For the Fishes, a coral reef restoration project. Forty percent of these fish won’t live to see an aquarium, dying in transport, and nearly all survivors will be dead within a year.

And those are conservative numbers based on reported take, experts said; the actual take could be 2.5 times greater.

“When the state opened the door to this trade in 1953, policies reflected the view that the ocean is a stable and endless resource,” said Renee Umberger, director of For the Fishes. “The ocean today tells a different story.”

After hearing several expert testimonies, the Kaua‘i County Council on Wednesday unanimously voted to include in the 2012 Kaua‘i County Legislative Package a proposed draft resolution asking the Legislature to issue a statewide ban on the aquarium trade.

“Forbes Magazine” in October reported that Americans feel the economic value of Hawai‘i’s reef ecosystems is worth $34 billion annually, said Councilman KipuKai Kuali‘i, who delivered a comprehensive presentation at Council Chambers.

Aquarium trade in Hawai‘i is an industry that generates $1.2 million annually, employing less than 100 full-time collectors, according to Kuali‘i. Compared to Hawai‘i’s snorkeling and diving business, which generates approximately $306 million annually and employs thousands of people, aquarium collecting is only a fraction of the economy.

But unchecked, the aquarium trade’s consequences could be far-reaching. Experts are saying in some parts of the state over-collecting has reduced species considerably.

In the mid-1980s the state reported the aquarium trade collected fish on O‘ahu’s southwest reefs to the point of commercial collapse, according to Umberger.

Today, the “hub of commercial aquarium collecting” in the state is along Big Island’s Kona side, said Robert Wintner, executive director of The Snorkel Bob Foundation.

Big Island’s Kohala Coast is often referred to as the Gold Coast because of luxury resorts. But the real reason this strip of coast on the west side earned this nicknamed was an over-abundance of yellow tangs rolling with the breaking waves created an impression of golden waves. Today there are barely any yellow tangs there, he said.

Umberger said the state Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Aquatic Resources in 2010 “conceded” that the aquarium trade has caused the number of yellow tangs to drop by 73 percent in Big Island’s west coast.

In the 1990s an impact study showed that the trade on Big Island’s west coast caused some of the species to reduce by 97 percent, Umberger said. A community rally 11 years ago for a ban was able to close 35 percent of the coast.

The closure has allowed a few, but not all, species to increase populations within the enclosed areas, she said.

“Along the majority of the coastline, our worst fears are coming true: Populations and entire species are disappearing,” Umberger said.

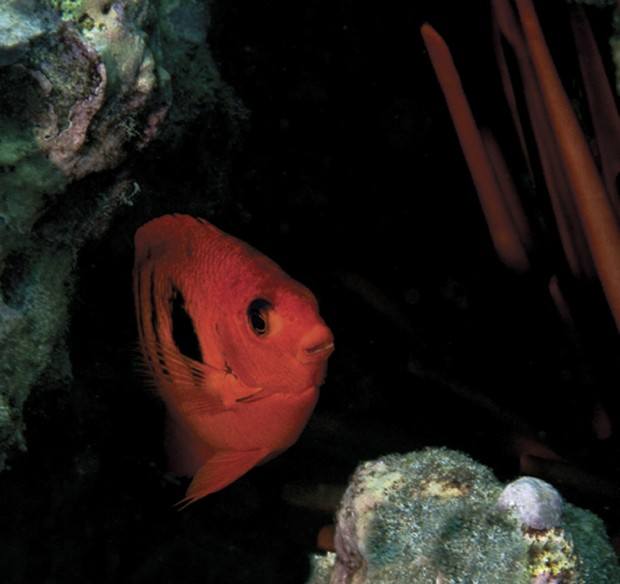

Kaua‘i fish targeted

The aquarium trade is a major source of reef degradation, as reported in 1998 by DLNR, Kuali‘i said. The trade takes species away from the ecosystem, disrupting food webs. Cleaner wrasse remove parasites and herbivores — 80 percent of collected fish — keep the algae in check.

Up to 40 percent of fish collected in Hawai‘i die before reaching a hobbyist, and 50 percent of the state’s top-20 fish are not guaranteed to arrive alive when purchased online, according to Kuali‘i.

Wintner said after reaching a hobbyist, nearly all aquarium fish die within a year of captivity.

He and Umberger warned council members that over-taking in Kona has caused many species in Big Island’s west coast to become rare or disappear, increasing their value in the market.

“The aquarium trade now hunts these big-money, big-status species on Kaua‘i,” Wintner said.

In 2010, an O‘ahu man died on Kaua‘i after three deep dives in three consecutive days in pursuit of the extremely rare and expensive masked angelfish. The man found these fish at depths of 250 to 300 feet. Wintner said the man was diving with a re-breather — scuba equipment that recycles breathed air and allows for longer dives — and on his third day diving he died two hours after resurfacing.

Just prior to the man’s death a pair of masked angelfish was sold for $30,000, according to Wintner.

Umberger, a Maui resident, said she’s been diving for decades. Up until last month she and others were able to spot a pair of the elusive masked angelfish during regular dives at Molokini, a half-moon shaped small island off the coast of Maui. The fish are now gone and Umberger suspects they were captured and sold.

Another species fetching a high value in the market is the bandit angelfish, retailing for $800, according to Wintner. The bandit angelfish became so rare in the Kona coast that it may have been gone altogether there and collectors are now targeting Kaua‘i.

Another fish once common and now rare in Big Island’s west coast is the lion fish, also being targeted on Kaua‘i, he said.

Wintner also said people have to be careful not to blame the aquarium trade industry entirely in reduction of fish populations, as there are other factors that may have played a role, such as hurricanes, runoff and pollution. But even then, he said the state shouldn’t allow collectors to pick what is left from the ocean.

“Would you let them take the nene?” said Wintner, alluding to the endangered status of the Hawai‘i state bird, which at one point was a hair away from extinction, with only about 30 birds left in the wild.

• Léo Azambuja, staff writer, can be reached at 245-3681 (ext. 252) or lazambuja@ thegardenisland.com.