Kapaia bridge towers to be stabilized

KAPAIA — How much does it cost to restore a historic monument? Apparently, it depends on who is asking. It could be as low as a decent used car or as high as pristine oceanfront property.

Mayor Bernard Carvalho Jr. announced in May that his administration would not be pursuing the restoration of the historic Kapaia Swinging Bridge. His reason was straightforward: Honolulu consultant Kai Hawai‘i estimated it would cost county taxpayers $4 million.

However, the myriad details in the bridge restoration issue are anything but clear cut.

The bridge, inaugurated in 1948, served plantation workers who lived in the area. The county built the bridge, but the land surrounding it belonged to Grove Farm. The company has sold most of the property to private landowners, but still owns some land behind the bridge.

In other words, the county owns the bridge but can’t access it. The access, county officials said, would cost just shy of $2 million.

If private landowners would donate land to the county to provide access, it would still leave the project at a little over $2 million, the figure for the bridge’s restoration that Kai Hawai‘i initially produced.

“We always said from the beginning that the figure that the county came up with was outrageous,” said Laraine Moriguchi, president of the Kapaia Foundation, a group of community members trying to save the bridge.

After Kaua‘i County Council members asked the administration to come up with a second opinion, county Managing Director Gary Heu said the consultant identified a few cost-saving measures.

The original bridge was made of redwood, he said. If the county decided to go forward with the project using Douglas fir instead, the price of the wood alone would go from $800,000 to $400,000.

Council members have publicly said that if government and private citizens would get estimates for materials and labor from the same retailers and contractors, the figures would come in different; government always gets a higher estimate.

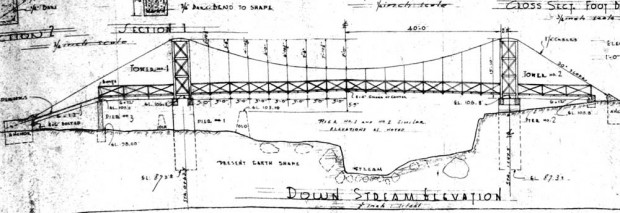

But if one of the locals who lives near the bridge is right, the discrepancy in the wood pricing is serious. The Kapaia resident, who spoke on condition of anonymity, took the bridge’s original blue prints, dating back to 1943, and went to a couple local retailers to price every piece of wood in the bridge.

The end result was $9,000 for all the wood in the bridge. And the suspension cables would cost $3,000, he said.

He said some local contractors came by and, after looking at the bridge, said the materials should cost about $25,000.

The Kapaia resident said the difference between his pricing and the consultant’s estimate is what he calls “padding,” hitting his hands on his pockets.

Stabilization

Moriguchi owns a large piece of property right next to the bridge, plus a small business next to the bridge’s footing. She said her father bought property there in 1971, and over the last 40 years she has seen the bridge deteriorate.

The bridge has two main towers, which are threatening to come down. If that happens, the restoration work would be costlier and more difficult.

So the Kapaia community — two months ago — asked the council to release $20,000 to stabilize the bridge until it could be entirely restored.

On Wednesday, County Engineer Larry Dill gave an answer to the council. He said the consultant estimated bracing the bridge’s two towers would cost $60,000.

Since the bracing would cost just as much as replacing the wood in the towers, Heu said the administration will be pursuing the replacement instead.

Kapaia community members have attended numerous council meetings when the bridge’s restoration was an item on the agenda, only to find out they had been stood up by the administration. This caused frustration for the lack of communication.

“In the last meeting they made up for everything,” Moriguchi said. “I’m happy, at least they are going to do something.”

She said the residents were determined to stabilize the bridge even if they had to do it on their own. “So this is a really big help that they’re going to take care of the towers.”

Moriguchi said she hasn’t lost trust in the administration or in Dill, who she said “seems really sincere.”

But she still hasn’t forgotten broken promises.

“I hope they are going to do what they say they’re going to do, because they said it before and they didn’t come through,” she said.

Permits needed

In order to go ahead with the towers’ replacement, Dill said the administration would first have to secure an array of permits or approvals from various county, state and federal agencies.

The county Public Works Department would for sure need approval from the State Historic Preservation Division and possibly from the state Disability and Communication Access Board. Zoning permits from the county would also be needed.

If federal funds are used, the county would have to apply for a Section 106 Historic Preservation Review, which relates to archaeological surveys looking for possible sites.

Other potential but unlikely permits could be required by the Department of Health Water Quality Certification, Department of Health National Pollution Discharge Elimination System and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Clean Water Act. An Environmental Assessment would be unlikely if a historic restoration is pursued, Dill added.

The county would probably pay higher wages to construction workers, because it follows the Davis-Bacon Wage Determination. So work to replace the wood in both towers would likely cost between $80,000 and $100,000, Dill said.

The council has secured some $240,000 from the county’s capital improvement budget to be used toward the bridge’s restoration, and the money for the bridge’s stabilization would come from that fund.

Befuddled council members

SHPDbranch architect Angie Westfall in June told the council the bridge design presented by Kai Hawai‘i was not the same design of the actual bridge. If the administration would pursue that alternate design the bridge would not be historic anymore.

“It’s basically a Disneyland version of the bridge,” said Westfall, explaining that the entire bridge would be taken down except its concrete piers.

Council members — under the impression that the consultant’s design was identical to the original bridge — asked Heu why a different design was presented to them.

And besides, it cost the county over $100,000 for a design that will probably not be used.

Heu said the council had asked for a usable, safe pedestrian bridge, and that was exactly what the consultant came up with: a bridge two feet wider than the original one, with longer access ramps and in compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

The administration decided to do it right, Heu said, and there are different interpretations of what is right.

The bridge may be exempted from ADA compliance if a historic restoration is followed, which would lower the construction cost. But council members also asked if the bridge becomes just a monument, then it’s also a tourist attraction, so there might be ADA requirements at least for a parking lot.

The question of whether the bridge has to be ADA compliant is still not fully answered, but at least one council member has said that morally, the bridge should comply with ADA, because society had made a commitment not to leave anyone behind because of mobility impairments.

Historic on paper

Council members may have opted to discard the consultant’s bridge design in favor of a true historic restoration, but the bridge standing there today is not the same bridge build in 1948.

The bridge’s original blue print, from 1943, shows odd lumber sizes were used, such as 3’x3’ or 6’x6’ beams. Those measurements are not sold in today’s market, according to the Kapaia resident who priced the materials.

The simple solution would be to bring the wood to Kaua‘i Community College and let the carpentry students mill the lumber to the bridge’s original specifications, he said. The community would then get together, and using a local contractor’s license, build the bridge with volunteer sweat.

The railings are also different. In the 1943 design they have a cross-pattern, while the ones in the actual bridge have a horizontal pattern.

Moriguchi said the county did some restoration work on the bridge up until September 2006, when the bridge was closed off.

“When they repaired it previously they must have changed it,” said Moriguchi, adding that when the bridge is restored it will be following the 1943 design.

The swinging bridge is actually called a suspension bridge and a foot bridge in its original blue print. The previous bridge, washed out in a flood, was also called a foot bridge in the county’s 1928 documentation.

The original bridge had steel cables running low alongside the bridge, through eye bolts shown in the 1943 blue print. Those cables, not there anymore, helped to keep the bridge from swinging sideways, the Kapaia resident who priced the lumber said.

The county used to maintain Laukini Road, linking the bridge to Kuhio Highway. But when the bridge was closed in 2006, the administration found out Laukini was a private road and stopped maintaining it, Moriguchi said.

Optimistic future

Kapaia residents have brought up the issue of pedestrian safety at council meetings. Council members share this concern.

Bridge supporters said Hanama‘ulu residents who walk to work in Lihu‘e put their lives at risk each time they get on the bridge on the main highway, the only way to get across Hanama‘ulu stream. The pedestrian line on the bridge is just too narrow, about as wide as a baby stroller supports say they have seen being pushed there.

Moriguchi said the Kapaia Foundation is willing to work with the administration to identify additional funding sources to complete the entire restoration of the bridge. The announcement that the administration is moving forward in stabilizing the towers was received as a significant step toward bringing back the old bridge.

“We are very happy that they are going to take care of the towers, because that’s more than half the battle,” Moriguchi said.

From now on the foundation’s focus will shift.

“We’re willing to try to get funds for the rest of the bridge,” she said. “We have applied for grants and we are doing fundraisers.”

• Léo Azambuja, staff writer, can be reached at 245-3681 (ext. 252) or lazambuja@ thegardenisland.com.