HONOLULU — An excavation crew recently made a startling discovery at the bottom of Pearl Harbor when it unearthed a skull that archeologists suspect is from a Japanese pilot who died in the historic attack on Dec. 7, 1941. Archaeologist

HONOLULU — An excavation crew recently made a startling discovery at the bottom of Pearl Harbor when it unearthed a skull that archeologists suspect is from a Japanese pilot who died in the historic attack on Dec. 7, 1941.

Archaeologist Jeff Fong of the Naval Facilities Engineering Command Pacific described the discovery to The Associated Press and the efforts under way to identify the skull. He said the early analysis has made him “75 percent sure” that the skull belongs to a Japanese pilot.

He did not provide specifics about what archaeologists have learned about the skull, but said it was not from one of Hawai‘i’s ancient burial sites.

They also contacted local police and ruled out the possibility that it’s from an active missing person case, said Denise Emsley, public affairs officer for the Naval Facilities Engineering Command Hawai‘i, which was being inundated with media calls Wednesday about the skull from international news organizations.

The items found with the skull, which was determined not to be from a Native Hawaiian, provided some clues: forks, scraps of metal and a Coca-Cola bottle Fong said researchers have determined was from the 1940s.

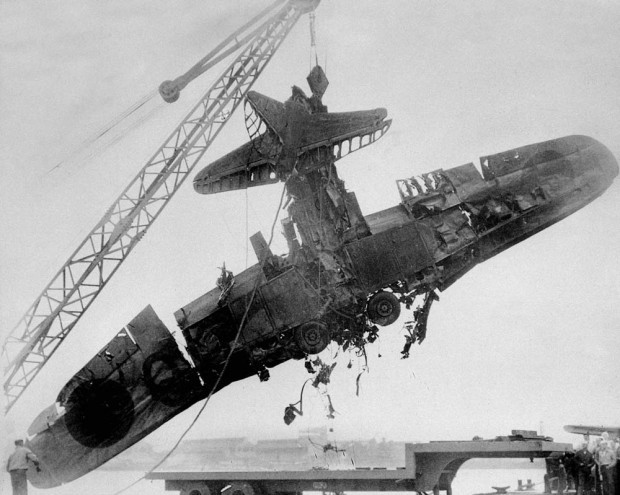

Fifty-five Japanese airmen were killed and 29 of their aircraft were shot down in the attack, compared with the 2,400 U.S. service members who died. No Japanese remains have been found at Pearl Harbor since World War II.

Pearl Harbor is home to the USS Arizona Memorial, which sits on top of the battleship that sank during the attack. It still holds the bodies of more than 900 men.

The skull remains intact despite being dug up with giant cranes and shovels.

It was April 1 when items plucked from the water during the overnight dredging were laid to dry. When it was determined a skull was among the dredged items, contractors were ordered to stop the work, Emsley said. “We definitely wanted it to be handled correctly,” she said.

“That’s why it’s been kept quiet. We didn’t want to excite people prematurely,” she said.

The Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command on O‘ahu, charged with identifying Americans who were killed in action but were never brought home, has been asked to determine who the skull belongs to.

The cranium was turned over to the command’s lab for tests that will include examining dental records and DNA, said John Byrd, the lab’s director and a forensic anthropologist.

The lab is the only accredited Skeletal Identification Laboratory in the United States. JPAC has identified more than 560 Americans since the command was activated in 2003.

When more information is gleaned from the skull, other agencies could get involved including the Naval Criminal Investigative Service and the Japanese Consulate.

“At this point it’s just a hypothesis, it’s not a conclusion,” Byrd said. “It might be very interesting or it could be very mundane.”

It’s rare to find remains in Hawai‘i, said Kohei Niitsu, an official at Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare in Tokyo.

“The government usually sends a team to determine if the remains are indeed Japanese, and if this is confirmed, they are brought back to Japan,” Niitsu said.

NAVFAC Pacific issued a statement late Wednesday saying it was too early to identify the remains.

“Until we receive the final report of the forensic analysis being conducted by scientists at (JPAC), we won’t know with certainty whether the remains are a Japanese pilot or not,” the statement said.