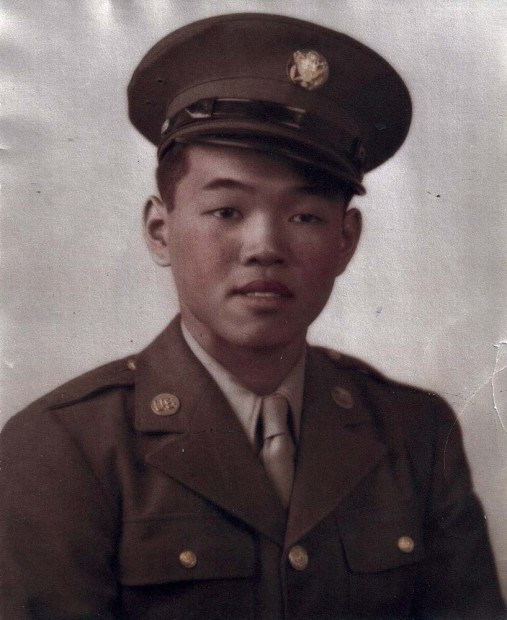

LIHU‘E — Joseph James Lee didn’t like to talk about his experiences in World War II. When his days as a soldier were over, he put the past behind him and went about building a life and family.

Now at 87 years old, Lee decided to honor a request from the Kaua‘i Veterans Center to have his story recorded with those of other veterans for posterity. This led to an interview with Loya Whitmer, who worked closely with Lee over the course of a year to get him to answer a question now and then, which was difficult with his deafness, and to reflect on his time as a tanker and guard at a Japanese prisoner camp in the Philippines.

“I was never much to talk about my military days because it was a very unhappy time of my life; not only my life, but millions of people’s lives, especially those families that had sons killed in the war,” said Lee.

“It was a universally unhappy time. Everyone was affected, civilians too, due to rationing, curfew, blackouts, etc. Factories were converted into weapons and munitions factories, men and women worked 16 hour days, double shifts and many other factors.”

The search for

‘Goam Sohn’

Lee was born on June 27, 1924, in Minneapolis, Minn. His father, Hong Lee, was born in San Francisco, but soon returned to China where he was raised. In 1918, Hong and his Cantonese wife Ying Moy took a boat to Seattle and a train to Minneapolis, where a nephew was already living. It was the search for “Goam Sohn” or “Golden Mountain,” Lee added.

Lee was pretty much a straight-arrow kid and worked at the famous Nankin restaurant in downtown Minneapolis. He said it was when Pearl Harbor was bombed on December 7, 1941, that “really turned on the lightbulb in many of us.”

Pearl Harbor

“That was the first time I ever knew that our country rallied together to fight the war,” said Lee. “So it was the bombing of Pearl Harbor that brought us all together.”

Lee recalled feelings of hatred toward Germany and Japan for starting the war. “Why would humans want to kill other humans? I think that was the universal feeling, not just mine.”

Lee didn’t share the same sentiment for Japanese Americans, and reflected on the 120,000 that were put into interment camps.

Many Hawaiian soldiers of the Hawai‘i Provisional Infantry Battalion would fight with the 100th Infantry Battalion and later the mainland Japanese would join them to form the 442nd Regimental Combat Team — the most decorated unit of its size in U.S. military history.

“These American Japanese fought in Italy and were heroes, almost every one became a hero,” Lee said.

Lee and two of his brothers were all drafted at different times. They would all survive the war.

Henry, the eldest brother, went into the Army in 1942 and fought in Germany until 1945. He was wounded by shrapnel and receives a 10 percent disability. His other brother Fred served for three months and was given a medical discharge for skin disease, eczema and allergies.

Second Army

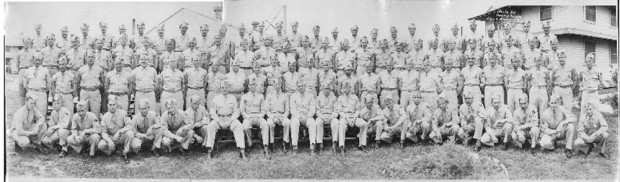

Lee would serve in the Second Army, mostly with 786 Tank Battalion, B Company, C Platoon. He was a gunner and recalled they were trained to do all five primary tank jobs — tank commander, driver, assistant driver, 50-caliber machine gun and 76-millimeter cannon gunner, cannoneer (loader) — in case someone was injured or killed.

“My job ended up ruining my hearing,” he added. “So I receive a military disability also.”

Lee said his parents expected one of them to serve but were not happy at first about all three of them in the war. Lee said they were drafted and considered it their duty.

Once the brothers were serving, Lee said their parents were proud of them.

“I was proud to be of service to the United States of America and wear the uniform,” said Lee. “Plus, the camaraderie I had with fellow soldiers.”

That belief helped Lee through the darkest days of the war, when he said the time away from family and the “unknowing” if he would ever make it home was the worst.

Lee recalled that he and one other soldier were the only two that didn’t smoke or drink in his company. He would watch his friends drink bottle after bottle of beer until they were intoxicated and then take the late bus back to post. His first attempt at drinking was on a double date when they were passing around a whiskey bottle. He had too much and slept it off at the USO.

“The next day, my friend and the two girls picked me up and took us back to camp,” said Lee. “As a result, I quit drinking. I couldn’t stand the sight or thought of whiskey.”

A time for reflection

Lee said that part of the reason he began to reflect on the war came from a recent visit to Pocatello, Idaho, a full 66 years after he was assigned as a guard on a train that was moving his unit’s tanks and equipment to San Francisco from Fort Carson, Colo., in 1945. They were to ship out to the Philippines and the move was a winding course to confuse the enemy of a major deployment.

“Of course we did not know we were going to the Philippines,” said Lee. “We were going overseas, but we did not know where we were going. No one knew where except the officers in charge.”

Lee recalled that he and about a half dozen other soldiers would guard the equipment by jumping from flat car to flat car on the moving train — something he is not sure he would do again.

“I thought at the time it was safe, but now I wouldn’t do that jumping from flatbed to flatbed on a moving train going 40 miles an hour down the track, zigzag through mountains, by rivers, forests, through cities and a bunch of small towns.

“It doesn’t look very far on a map, but it took weeks to get there because we had to take a zigzag route so nobody would know where we were going,” he added. “We sat on a siding — a side track — for hours or even a day.”

All they had to eat was Army C-rations and D-rations. When they pulled in to Pocatello, Idaho, Lee said the townsfolk came out to wave and to thank them. Someone produced a shoulder bag of candy and passed it out to them, asking them to “come back and visit after the war.”

“That was so special because we had not had any candy,” he said.

It was on May 1 when Lee and “his love Loya” made their way to see her sister Camille, in Idaho Falls, Idaho. While there, he made the trip to Pocatello and began reminiscing.

Lee recalls the transport ship stopping at Pearl Harbor on the way to the Philippines. He took sick with tonsillitis and was admitted to sick bay with a 104-degree temperature.

The Philippines

When Lee’s unit arrived in the Philippines, it was still primarily the same group he had trained with at Fort Knox, Ky.

They were mainly comprised of Texans, with fewer from across the country, including three from his native Minnesota.

The Philippines had already fell from Japanese control and was now in the hands of the allies. The unit became responsible for guarding a Japanese prisoner of war camp and for guard duty and taking the prisoners on daily work details.

Lee was put in charge of Japanese prisoners working the company laundry. The laundry consisted of 55-gallon drums that were cut in half, length-wise, and the men would work on scrub boards placed in each half-barrel using “GI soap.”

He recalled that about two or three of the prisoners would work as his interpreters and would get the word across what had to be done and how to do it. He even became friends with the ones who worked with him. He recalled that they were good workers and were always wanting to learn more English.

“They would give me massages and hair cuts,” he added. “Even today, I still cherish my weekly massages.”

Lee said that his prisoners were ordinary men like himself that were forced to go to war. They were not fanatical. When the time came to surrender or die, they were willing to surrender.

“They were more gentlemen rather than hardened warriors,” he said. “On the other hand, there were some men that wanted the war. They were the men that would not surrender. They would rather die than surrender. Many Japanese would prefer killing themselves rather than surrender.”

Lee recalled a routine of taking part in battle simulations and tank maneuvers and searching the hills for hiding Japanese soldiers that didn’t yet know that the Philippines were now under the firm control of the allied forces.

“We would find some that thought we were still fighting, and they would still be firing on us, so we would have to kill them,” he added. “And sometimes at night, they would come down from the hills to steal food because they were starving.”

The Bomb

Lee said the invasion of Japan that was to start in the fall of 1945 was halted when the war ended in August after two atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

“The atomic bomb was our salvation! We were training to attack Japan,” he said. “We found out after we went into Japan after the war ended, we would not have survived attacking Japan, because Japan was so well fortified.

“There are some people that criticized the U.S. for using the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, but it was a necessary to end the war,” he added.

Back home

Lee was discharged at just 20 years old in April 1946. He returned to Minneapolis and attended electronic repair school, started a television sales and repair business. Six years later, he married Darlene DeBruyn in Aug. 1950. The couple raised two daughters — one is now an employee for Delta Airlines in Minneapolis and the other is a veterinarian in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Joe and Darlene divorced in 1982 and she passed away in 2000.

Lee also operated several Chinese restaurants, including The Rose Garden, Riverside Garden, Kauai Garden and the Dynasty. In 1988 Lee retired from all businesses at retirement age. In 1990 he went back to work in golf course maintenance in Minnesota for five years. He then moved to Florida and worked in golf-course maintenance another five years until age 75.

Since leaving the service, Lee said he believed that by putting the war out of his mind, it helped prevent thinking or dreaming about the past too much.

Lee’s first visit to Kaua‘i was with Darlene in 1979. He visited Hawai‘i as a divorced man 13 more times 13 times between 1982 and 2002. He moved to Kaua‘i permanently on July 4, 2003. The friends he moved here to be near died soon after, but Lee decided to stay on the island.

“I liked Maui the best, but moved to Kaua‘i because of friends that lived here,” he said. “So I am still here even though my two daughters want me back in the Midwest. I cannot stand winters. I am a lover of warm weather.”

He said the war didn’t teach him much that helped in civilian life; however, his years as a gunner have made him an excellent hunter. He said that managing prisoners helped him with running a business.

Most of all, Lee said his keen appreciation for exercise and its good for the body stems from the military and the clean life he has chosen to lead.

“I continue to exercise my body,” he said. “I usually run two and a half or three miles twice a week.

Part of the reason that Lee hesitated from telling his story for so long is that he didn’t want people to think of him as a hero. He said the heroes are those who gave the ultimate sacrifice for their country, and that he considers himself an ordinary person who served his country to the best of his ability.

Loya Whitmer interviewed Joseph James Lee and transcribed the notes from which this story is based. She said that Joe Lee’s story is to encourage all veterans to be interviewed and to add their voice and experiences to the Military History Institute in Carlyle, Penn., and to the Library of Congress.

Begin by contacting the state of Hawai‘i Veterans Services in Lihu‘e at 241-3348.

• Tom LaVenture, staff writer, can be reached at 245-3681 (ext. 224).