MOLOA‘A — Sitting on the lanai of his Moloa‘a home, Charles Perreira spreads out a throw net he has been working on for the past three weeks. “I have this list of names of people who want the net,” he

MOLOA‘A — Sitting on the lanai of his Moloa‘a home, Charles Perreira spreads out a throw net he has been working on for the past three weeks.

“I have this list of names of people who want the net,” he says as he picks up multiple strands of string.

Perreira begins to effortlessly weave his net. The sounds of the ocean fill his lanai as he begins telling stories of his wife Loke, who passed away days after they were honored as Living Treasures by the Kaua‘i Museum.

“We were married 53 years,” he says with a sad smile. “This year was 56.”

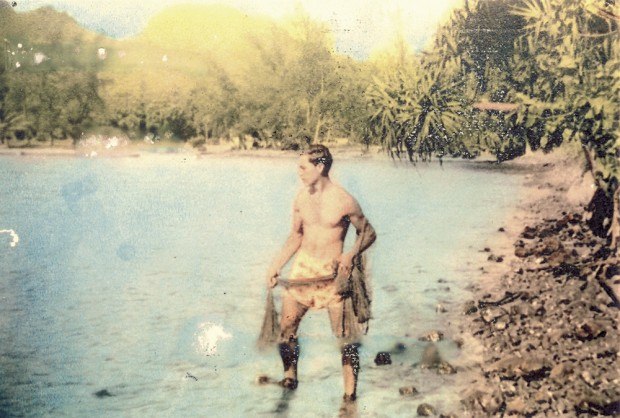

The hand-painted hat he is wearing shows a man standing on the shore throwing a net into the ocean. His red T-shirt, a gift from his grandson, reads “If things improve with age, I’m getting pretty near perfect.”

The 81-year-old suddenly stops weaving, looks toward the ocean and says, “There’s something about this bay. It makes you feel good. All my life has been the beach. Even from the time I was in the military. I always thought about coming home and being close to the beach. It’s relaxing in a way.”

Perreira’s one-bedroom home is filled with personal treasures: He has framed pictures of his wife and two children, a milo wood bowl resting in front of a nose flute, his award from the Kaua‘i Museum, relics from his military days and a lifelike painting of himself weaving a net.

Perreira doesn’t own a television or radio. Instead he passes his time sewing throw nets, a practice he learned from his father when he was 12 years old.

Perreira uses a bamboo needle, a spacer to determine the size of the hole and more than 3,000 yards of string or monofilament for each net. Spread out, his nets range anywhere from 10 to 20 feet in diameter. After he’s finished weaving, Perreira spends hours melting lead to create weights he sews onto the perimeter of each net.

He plans on selling the net he is currently on to a young Hanama‘ulu father who works in construction.

“He came by and asked me how much, and I said ‘How much do you think you can give me?’ Today, they pay this thousand dollar house rent. They have a truck to pay. I kind of think about it.”

In Perreira’s eyes, it isn’t how much money he sells each net for, it’s who the net is going to.

“The last one gave me money in cookies,” Perreira said with a laugh. “It was for her future son-in-law. She bought the net and took it home. She told him, ‘Go to the truck, there’s something real heavy and I cannot lift it.’ When he got there and opened that door and he seen that net, he had tears in his eyes.”

Perreira’s nets have ended up in the hands of fisherman on all the islands except for Lana‘i.

He has taught three people this tradition. One of his apprentices, Chuck Meek, was inspired to write a song titled “Uncle Charlie.”

Accompanied by an ‘ukulele Meek sings, “Old Charlie he’s a master. He’s made more nets than most. From the shores out in Ha‘ena, out to Kohala coast. You can bet his nets will hold the fish. He makes them good and strong. And if you no more money, He give ‘em for a song.”

Fellow Living Treasure Larry Rivera also recorded a song in Perreira’s honor. The chorus goes: “Weaving, weaving, hands that God has blessed. Weaving, weaving, nets that is the best.”

As a boy, Perreira worked on the plantation before joined the military where he met his wife at Schofield Barracks on O‘ahu. After he retired from the military, Perreira worked construction for a short time before he was hired as a groundskeeper at the “good old Coco Palms” for 24 years.

Today, Perreira is never without his net.

“At parties I get out my net and sew. Even at funerals, afterwards, I sit down and sew my net.”

After seven decades of net making, Perreira is confident in the quality of his nets.

“When they bring me fish they caught, I know the net is good.”

• Andrea Frainier, lifestyle writer, can be reached at 245-3681, ext. 257 or afrainier@ thegardenisland.com.